We attended our first childbirth preparation course last week, Pete and I. It was 2.5 hours long, on Zoom, and would have made an excellent drinking game (drink every time you hear the word blood! Or mucus!) had I been drinking. Instead, we just watched it in bed on my laptop, passing a block of cheddar cheese back and forth while Pete drank enough whiskey for both of us.

The instructor (Linda? Laurie?) flipped through slides on the various Signs of Labor and Stages of Pregnancy at a brisk clip. All the titles were capitalized, like biblical plagues or Liam Neeson films: The Breaking of the Bag of Waters, Bloody Show, Effacement. In an irritating grammatical quirk that I’ve noticed in a lot of health practitioners lately, she never referred to an infant as “the infant,” or “the baby,” but just Baby. (It doesn’t take much to irritate me, lately.)

I couldn’t help thinking of last week’s eclipse as they showed the “vivid animation” of a dilating cervix. As it vividly reached 10 centimeters, I turned to Pete and yelled, “Totality!” Other than that, there were only two other parts of the class I cared to reflect on afterwards: First, when the instructor pushed a doll through a knitted uterus to simulate contractions, and second, when she brought out a (real?) human pelvis and demonstrated how the doll might try to fit through it.

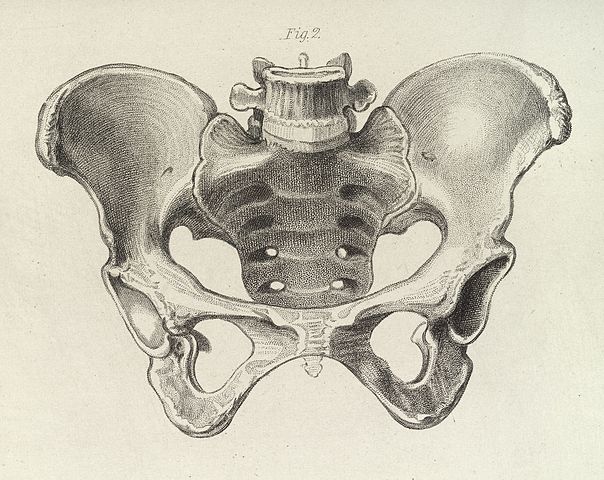

Bouncing gently on her birthing ball, Linda/Laurie manipulated the pelvic bones so they flexed apart and came back together around the doll head — like the Jaws of Life, I thought, or just Jaws. Watching the absurdly large-looking doll corkscrew its way through the birth canal made me think of scientists, past and present, who have observed the same thing and tried to figure out in what universe this makes any sense. In particular, I thought of the obstetric dilemma hypothesis — a long-accepted explanation for why human mothers have evolved to push their infants through such a narrow gap.

The hypothesis was first articulated in a 1960 issue of Scientific American, by a physical anthropologist named Sherwood Washburn. He argued that humans evolved narrower pelvises in the process of becoming bipedal, but that this poses a “dilemma” for women because it conflicts with the other evolutionarily advantageous adaptation of larger infant brains. Washburn concluded that females had been stuck with a painful compromise between walking upright efficiently, which a narrower pelvis enabled, and their babies’ growing heads.

Few challenged this hypothesis until the 2000s, when a handful of anthropologists, mostly women, started to ask whether having a narrow pelvis was really as important to efficient bipedal locomotion as Washburn had made it out to be. Through biomechanical studies, they found that having a broader pelvis and wider hips actually reduces the amount of energy a person spends walking or running, especially when someone is carrying a burden like a pregnant belly or a nursing infant. In addition, they found so much variation in the size and shape of the pelvis in women around the world that the notion that female locomotion is somehow inherently at odds with reproduction has started to unravel.

Although the obstetric dilemma is still widely accepted, it’s now just one of several competing hypotheses for why childbirth is difficult for humans, compared to other species. Other explanations have to do with the invention of agriculture, which may have led to women with smaller pelvises and bigger babies, as well as more recent increases in obesity and malnutrition.

For my own part, aside from trying to master pelvic floor exercises (that’s when my unborn child does a double back layout with a half twist on my bladder, yes?) I hadn’t really thought much about pelvises before, my own or others. But after watching our instructor heft one around, making the ilium, ischium, and pubis subtly expand and contract like wings, I finally understand why Georgia O’Keefe spent so much time painting them. Looked at one way, the pelvis is a cage, a maze, a trap. But from another angle — look, a window.

LOVE this!