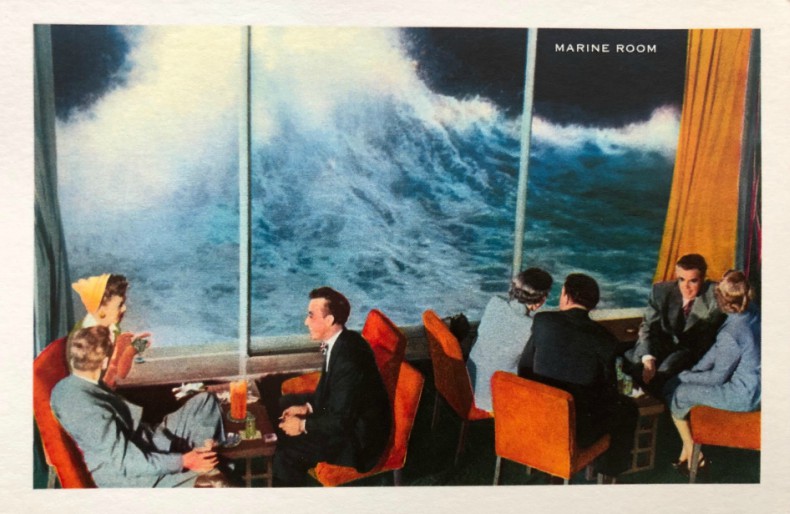

One of our cats, the gray tabby female, hasn’t been eating well lately. We’re not sure how long this has been going on. Has it been since late February, around the time the first victim of COVID-19 in Washington State died in a hospital 10 miles from where we live in Seattle? Did it start earlier, in the last days of January, when the country’s first coronavirus infection was diagnosed in the next county to the north? It’s difficult to keep track these days.

On a Friday in mid-March I take my uncertain timeline and both cats to the vet for checkups. She pronounces our other cat, the orange tabby male, healthy as the proverbial horse. But she lingers over the gray tabby, feeling her abdomen as a concerned look comes over her face, and that’s when I know everything has changed.

The vet feels some kind of mass. “It could be an enlarged kidney,” she offers, and I nod, but we both know it isn’t.

Driving the cats back home I wonder how I will tell my husband and, especially, my daughter. I run through my expanding list of other worries: my parents in Arizona, where no one in charge seems to be taking this virus seriously, my stepfather-in-law with chronic lung disease. Will 2020 be the year we lose everything? I wonder to myself, maudlin.

***

The gray tabby’s name is Daisy. She was a neighborhood stray we took in the summer my daughter turned two. I asked my daughter what we should name the cat and she pointed to some plants in the yard and said, “Flowers.” I don’t think she was really responding to my question but I felt obliged to honor her answer. Flowers is a pretty ridiculous name for a cat, but it was only a hop and a skip from there to Daisy, which suited so well it soon felt like it had been her name forever.

Maybe it’s the stress of the journey or maybe it’s just that now we know something is wrong, but Daisy seems much worse after returning from the vet. She hardly eats or moves all weekend.

My husband has been working on stocking our pantry, adding canned soup and four kinds of beans to a grocery order to be delivered late next week. He’s good with emergency supplies. He fetches a container of dry cat kibble from our earthquake kit in the garden shed. I didn’t even know we had it. It’s the worst, most junk-food-y kind of stuff, little poultry-flavored bits in a variety of different shapes, like kitty Lucky Charms. Daisy is ravenous for it. My husband weeps as she eats it out of his hand.

***

By the time the abdominal ultrasound we’ve scheduled for the following week arrives, our veterinary practice has instituted some new rules. No human clients allowed in the clinic. You call from the parking lot, and a tech comes out, masked and gowned, to pick up the cat carrier you’ve set on the ground six feet away from your own body.

The ultrasound confirms that Daisy has a six- to eight-centimeter mass in her jejunum, a part of the small intestine. It’s causing some blood to leak into her abdomen, and there are “infiltrates,” a medical term for ghosts of something-or-other, near her spleen.

The radiologist took a sample of the mass with a long needle, and now the vet asks if I want to send the biopsy to the pathology lab for examination. Why wouldn’t we? I think. The vet mistakes my confusion for hesitation. “You’ve already paid for it,” she says. So I say yes of course, go ahead.

The next day, confirmation: the mass is a large granular cell lymphoma – basically an aggressive form of an aggressive form of blood cancer.

One of my favorite things is to pick Daisy up, hold her on her back and bury my face in the thick fur of her belly. I won’t claim that she enjoys this, but she tolerates it, bless her. Of course her belly was shaved for the ultrasound, and now belly kisses have become one more in a series of small, everyday pleasures suddenly lost to me. Kissing her bald skin seems wrong, too intimate. And I don’t want to kiss the tumor underneath. How do we separate the body we love from the monstrous thing growing inside it?

***

Due diligence must be done, so I set up a consult with a veterinary oncologist. Under the circumstances, telemedicine will suffice. The oncologist offers options, quotes statistics: six months median survival with aggressive chemotherapy, two months without. How long is either one of those possibilities? I’ve lost my ability to gauge time. “With that said, there are always outliers,” the oncologist says. But her message is clear: the only real option for Daisy, as for us, is to shelter in place for as long as it takes.

These days there’s a feeling of being simultaneously in solidarity and out of synch with everyone else in the world. Other people are adopting and fostering cats and dogs from shelters during their self-isolation. Not us. I’m worried that if Daisy dies before this is over, our one remaining cat is not going to be enough for a family of three to get through a global pandemic. I wish I had stocked up on cats.

Continue reading →