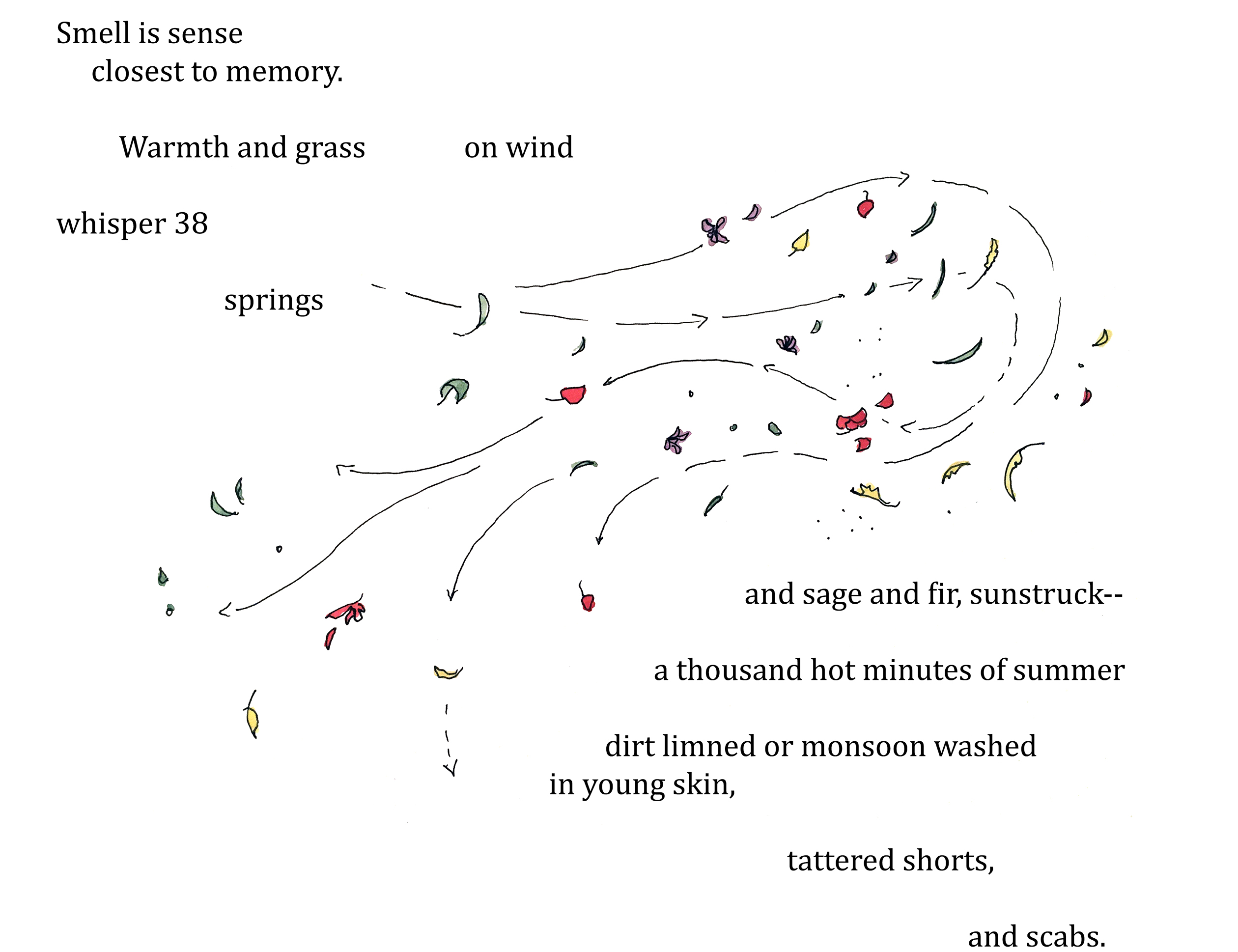

It’s the last day of summer for us, so I’m taking my summer feet to the beach. This post ran in August 2019. This year, school will look a little different, because we’ll all be barefoot.

At the beginning of summer, my feet often feel tender. There is a particular stretch of asphalt between the university parking lot and the beach that is especially pitted, and the sharp dark bits of broken ground make me cringe even before I step onto the road.

I often choose a different route to the beach, down the steep steps that are soft wood, worn by salt air and waves. But one of my friends likes to walk the bumpy path. While I dodge back and forth, taking a few steps on a curb, another on a small island of sidewalk, she charges straight down the bumpy asphalt. “I’m working on my summer feet,” she told me once. How good would that be, I thought, to have soles so thick that I didn’t feel anything?

But so far, I don’t have them. Even though the climate is mild here, I often wear shoes, even boots, in the winter. Even right now, in the dog days of summer, I’m typing this and I still have on the running shoes that I’ve been wearing since biking to school this morning. Hang on—okay, now they’re off. Socks, too. There’s the parquet floor now, smooth and just slightly cool, under my soles.

When I remember, I do try to go barefoot. It does feel relaxing. I do like feeling things like this, the texture of the ground, its temperature. There’s a sidewalk parking strip down the street with smooth, round stones that feels like a free acupressure session. And there’s such relief, on that pathway down to the beach, once my feet finally reach the sand.

But my feet never seem to get tougher. The gravel that runs along the side of the house always presses into my skin like tiny tacks, and I hop and skitter and hiss nasty things at it when I go to put the bikes away. And my feet accumulate all sorts of ugly things—black spots of tar, bee stings, moon-like calluses on the balls and heels.

Once school started, I found my shoes again. It’s too far to walk barefoot to school, and while I love seeing barefoot people riding beach cruisers, the idea of putting skin on metal pedals seems sketchy and uncomfortable. I have to bring out other protective layers, too–sunscreen and full lunchboxes, fresh school supplies and new socks. An encouraging yet increasingly insistent voice that gets homework in backpacks and bodies out the door. The promises that it will really be more fun at school than at home, where I’ll just be boringly typing things on the computer.

Humans have spent most of their existence without shoes. Now a lot of people wear them most of the time. But this means most people don’t have a chance to develop thickened soles; their feet are already cushioned from the earth’s rougher spots. So a group of researchers on several continents decided to look at whether calluses act differently than shoes when it comes to how well feet can sense the ground while walking.

The researchers compared shod participants to those who spend most of their time barefoot. They thought the calluses might reduce how well a foot could sense the ground beneath it, but it turned out that although calluses can provide a layer of protection against thorny patches, calloused feet were just as sensitive as those that spent most of their time in shoes.

I thought it was just more barefoot time that would help me get my summer feet, to feel nothing as I charged across the parking lot to the beach, to whistle as I walked on the gravel. I thought after six years of back-to-school picnics and pencils and pictures that this would feel like more of the same, that they would all run toward the classrooms at the sound of the bell, that I would run away. There would be nothing sharp that could penetrate us, that would make us stop and curl up and cry.

The calluses are there, trying to do their job of protecting me. Still, I’m tender about the end of summer, even with my thicker soles. Maybe they were never meant to stop me from feeling, but instead are making sure that I keep walking, feeling it all.

*

Image by Flicker user ɘsinɘd under Creative Commons license, 8/27/19