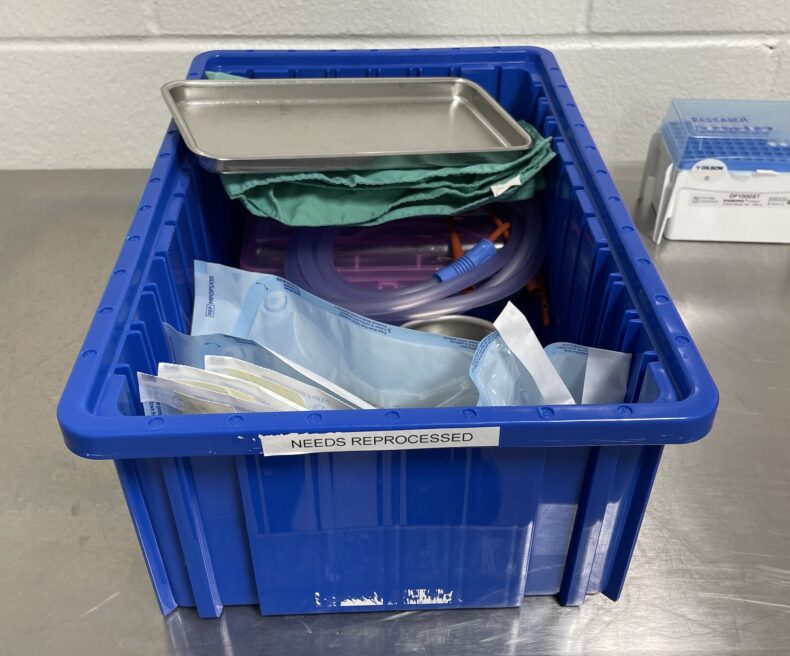

I took this photo in the veterinary lab at the Duke Lemur Center in October, on a tour at the National Association of Science Writers meeting. The bin sat next to a sterile operating room where, according to the scientist who was showing us around, they mostly do emergency caesareans for lemur mothers in distress. (None of the center’s research involves harming lemurs, I was relieved to learn.)

What caught my eye about the bin was not the stuff inside it, but the label on its outer edge. “Needs reprocessed” is a grammatical construction that will be familiar to anyone from Indiana, Ohio or Pennsylvania, but I’d never heard it until I met my husband, who grew up in central PA and says things like “the dishes need washed,” “my brakes need fixed” and “the dog needs fed.”

If you were raised to be a stickler about traditional English usage, like I was, this may make you grind your teeth. Most people in the northeastern US, the upper Midwest, and much of the West reject the construction, but there are pockets of people in Arizona, Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Montana who think it’s ok, according to this fascinating study from the Yale University Grammatical Diversity Project, which recently surveyed its use.

In regions where “needs washed” is most accepted, more than dozen other verbs can also get wedged in: “he deserves fired,” or “the paperwork requires completed” (gah!). It’s also commonly used for gestures of affection, like “the baby wants cuddled.” (I’m hearing a lot of that this week, since we brought our 5-month old baby to spend Thanksgiving with Pete’s family.)

“Needs washed” and phrases like it probably traveled to the United States with settlers from Scotland and Northern Ireland, according to the Yale researchers. When I saw the “Needs reprocessed” label at Duke, I was immediately intrigued — and also tickled by the odd juxtaposition of informal grammar against such a prestigious research setting.

It made me wonder who printed it out, and if it was meant to be funny or not. If not, I wondered further, was this research center a place where a person could just talk the way that came naturally to them? Where anyone could feel at home in science, no matter their backgound?

It was a nice thought — almost as pleasant as contemplating this pair of ring-tailed lemurs from Madagascar improbably perched in the woods of North Carolina. May we all feel this at ease, somewhere.