Before I begin, a disclaimer: I’m sick of writing about mammography. It feels like groundhog day — I’ve been writing the same damn story, over and over and over again, for nearly 15 years. [NOTE: This post you’re reading first ran in October, 2015, which means I’ve now been writing about this for well over 20 years.] This is at least the fifth time I’ve written a LWON post about mammograms. (See also: Breast cancer’s false narrative, The real scandal: science denialism at Susan G. Komen for the Cure®, FAQs about breast cancer screening, and Breast cancer’s latest saga: misfearing and misplaced goalposts.)

So why I am I writing about mammograms again? Because even though I just published a story at FiveThirtyEight explaining why science won’t resolve the mammogram debate and a feature at Mother Jones asking how many women have mammograms hurt? (the answer is millions) the harms of mammography continue to be ignored or mischaracterized in the media. Every time this happens, I get letters from people asking me to please clarify this point again. Just this past week, a New York Times editorial penned by two breast radiologists and a breast surgeon declared, “Let’s stop overemphasizing the ‘harms’ related to mammogram callbacks and biopsies,” while an op-ed in the Washington Post titled, “Don’t worry your pretty little head about breast cancer” claimed that, “the idea that anxiety is a major harm doesn’t have much scientific support.” (In fact, at least one study has found long-term consequences from a false alarm.)

What both of these opinion pieces miss and what too many women still don’t know is that while 61 percent of women who have annual mammograms will have a callback for something ultimately declared “not cancer,” this isn’t the most damaging problem. Such false alarms are more devastating than they might seem (I can’t think of another recommended medical test with such a high false positive rate), but most women would probably gladly accept this risk in exchange for a reasonable chance to prevent a cancer death.

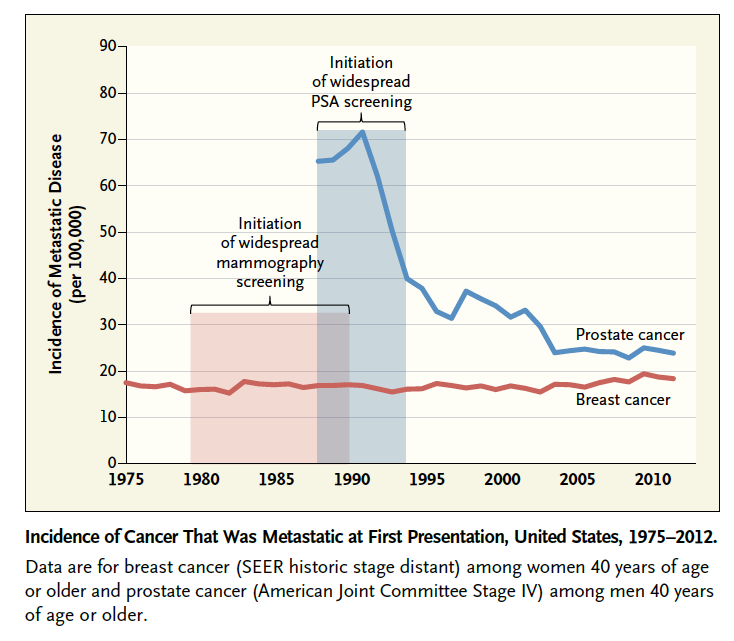

Here’s the bigger problem: screening mammography has failed to reduce the incidence of metastatic disease and it’s created an epidemic of a precancer called DCIS. The premise of screening is that it can find cancers destined to metastasize when they’re at an early stage so that they can be treated before they turn deadly. If this were the case, then finding and treating cancers at an early stage should reduce the rate at which cancers present at a later, metastatic stage. Unfortunately, that’s not what’s happened.

This graph published yesterday in the New England Journal of Medicine charts the bad news. (The situation is more nuanced for prostate cancer screening, and yet some medical groups have stopped recommending routine prostate cancer screening.)

Even if it didn’t reduce deaths, mammography might still be useful if it helped patients avoid the most aggressive treatments. But despite claims to the contrary, randomized trials have shown that participation in screening mammography increases the rates of lumpectomy by 30 percent and mastectomy by 20 percent.

A new paper just published by John Keen and Karsten Jørgensen in the Journal of Women’s Health lays out four principles that women need to understand before making a decision to undergo mammography screening.

Principle 1: Screening May Help, Hurt, or Have no Effect

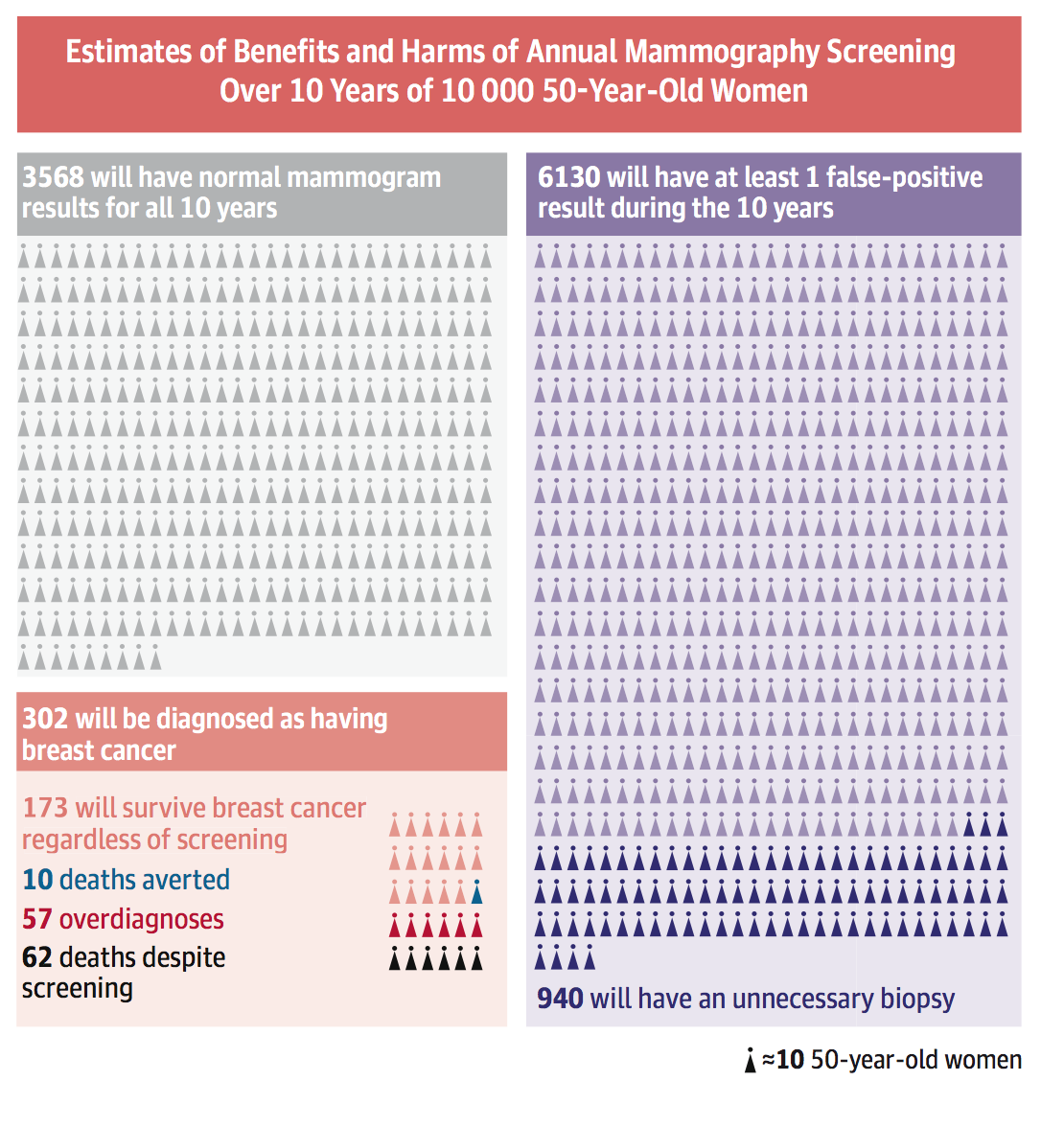

Women are often urged to get screened because it might save their lives. But that’s only one possible outcome, and it’s the least likely one. Here are the possible outcomes if 10,000 50-year-old women have yearly mammograms for ten years.

Principle 2: The Most Reliable Statistic for Evaluating the Benefit of Breast Screening is All-cause Mortality

Mammography is often promoted with claims that it can reduce breast cancer deaths by 15 or even 20 percent. But these numbers represent relative, not absolute risks, and they only consider breast cancer deaths. The average woman’s lifetime risk of dying from breast cancer is low — 2.7 percent without screening. Mammography also leads to the treatment of cancers that never threatened the patient’s life, and these treatments can increase mortality. All-cause mortality is the only measure that takes into account the harms from over treatment as well as the benefits from early detection, but “the benefit of breast screening on all-cause mortality is so small that hundreds of thousands of participants are required to test if the effect is there. The randomized trials, including >600,000 women, did not show an effect on total mortality, which tells us that the absolute benefit of the intervention must be quite small, if it is there,” Keen and Jørgensen write.

Principle 3: Some Plausible Screening Statistics can be Misleading

As I wrote here in 2012, some mammography advocates promote screening by claiming that it improves survival times. “The 5-year survival rate for breast cancer when caught early is 98%. When it’s not? 23%,” read one Komen ad. But survival time is a highly misleading statistic, because it depends entirely on when the cancer is diagnosed, not its ultimate outcome. People “overdiagnosed” with cancers that never would have never hurt them will have a 100 percent survival rate, even though their lives were never threatened. The more harmless cancers that screening finds, the better the survival rates look, even as more people are harmed.

Principle 4: Breast Cancer Biology Limits the Screening Window

In the end, it comes down to cancer biology. Some tumors can send out micrometastases very early, when they’re too small to be detected on even the most high-tech mammograms, and others can grow quite large without ever metastasizing. According to Keen and Jørgensen, what we call “early detection” is actually late in a tumor’s lifetime. They calculate that a tumor that’s 10-mm in diameter contains about one billion cells and has undergone 29 doublings. If you assume a median volume doubling time of 260 days, that means the tumor is more than 20 years old.

The median invasive tumor discovered due to symptoms is about 21 mm, and the median screen-detected invasive tumor is 14 mm. Do the math, and the difference in average size works out to about 7 mm or 1.4 years, but “in reality it is smaller because the many small, overdiagnosed tumors exaggerate the difference,” Keen and Jørgensen write. “The time window when screen detection might extend a woman’s life is narrow, as many tumors that can form metastases will already have done so.”

So what’s the takeaway?

None of the mammography studies we have is perfect, but in absolute numbers, there’s no question that far more women are harmed than helped by mammograms. Yet because the comparison is essentially apples to oranges (unnecessary treatments versus a life saved, for instance), deciding whether the harms are outweighed by the benefits comes down to a values judgement, not a math problem. If you’re a woman trying to decide whether or how often to get screened, go back to the chart under principle number one above, look at the numbers and decide for yourself whether the odds are acceptable to you. It’s your body and your choice.

Images: Header photo by Laura Taylor, via Flickr.

Chart of possible outcomes, from JAMA.

Incidence of metastatic breast cancer from NEJM.