A charming website called Who’s the Scientist? shows seventh graders’ images of scientists before and after actually meeting scientists. Continue reading

A charming website called Who’s the Scientist? shows seventh graders’ images of scientists before and after actually meeting scientists. Continue reading

When I was a child, my grandfather took me to London’s Trafalgar Square to feed the pigeons. Thousands of these statue-splotchers covered the square, feeding on seeds offered by the outstretched hands of excited tourists. It must have been a favorite outing, because he also took my mother and her cousin (left) out for a similar thrill when they were children. The seemingly innocent act was outlawed in 2003 by London’s then-mayor Ken Livingstone, who cited £140,000 worth of dropping-induced damage to Nelson’s Column. It turns out that it’s not just the long-dead Nelson who has reason to fear the pigeons: Spanish researchers at the Animal Health Research Center in Madrid have discovered that feral pigeons carry several nasty pathogens, including two that cause diarrhea in humans.

June’s solstice has just passed and I find myself where I usually am each year at this time—37,000 feet in the air and winging off to the field. One of the great joys of my job is to set out armed to the teeth with notebooks, cameras and voice recorder, and join an archaeological crew in some remote part of the world. Over the years, I’ve winced at mummy autopsies in Egypt, wandered ankle deep in mummified rats in a greathouse in New Mexico and wormed through caves in the northern Yukon, scouting for traces of the earliest migrants to the New World.

This morning, my destination is southern Arizona, where I’ll be joining Jason De Leon, an archaeologist at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his students on a field survey in the hilly backcountry of the Sonoran Desert. I can’t divulge any details about the story, but I will say that it has little to do with archaeology as it is usually practiced.

The weatherman predicts a scorching week, with temperatures soaring as high as 108 degrees Fahrenheit. De Leon tells me that the team heads out at 5 am each morning to take advantage of what little coolness there is and generally wraps up its field work at 1 pm. Team members fill their array of water bottles with ice each morning before setting out, but within a few hours, they are glugging down water hot enough to steep tea. And De Leon’s recommended gear includes a few things I’ve never seen before on an equipment list: a pocketknife with pliers for extricating cactus spines, instant icepacks, and something called hand coolers. Continue reading

Crop circles have moved well past circles. Now they’re jellyfish, dragonflies, and trilobites, drawn using higher math, computers, laser pointers, and GPS’s. A lovely little essay by a physicist in a recent Nature calls them “modern mathematical artworks” and hopes that this summer will produce a “bumper batch.” They seem to have no larger meaning, just that they’re quixotic, beautiful, and I thought you’d like them. Continue reading

Crop circles have moved well past circles. Now they’re jellyfish, dragonflies, and trilobites, drawn using higher math, computers, laser pointers, and GPS’s. A lovely little essay by a physicist in a recent Nature calls them “modern mathematical artworks” and hopes that this summer will produce a “bumper batch.” They seem to have no larger meaning, just that they’re quixotic, beautiful, and I thought you’d like them. Continue reading

Pay attention to the quote below the drawing. John Archibald Wheeler was a physicist whose specialities were nuclear physics, gravitation — he created the term, “black hole” — and getting people riled up. He died in 2008 at age 96.

I mean, when Victor Hugo writes that science says the last word on nothing, his sentence is beautiful; but then, he was a writer, and besides, what would he know? When John Archibald Wheeler says it, you can take his word for it

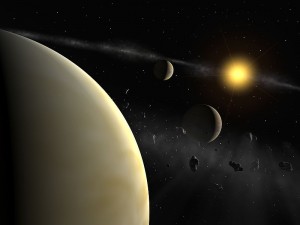

The word, “data” – tables of numbers, incomprehensible graphs — for most of us would make a good sleep aid. For astronomers, though, “data” means a star-sized thing that outshines a galaxy, or a galaxy just being born, or a star that spins in milliseconds. Data for astronomers is a way to survive, a reason to live, a combination of money and ice cream. So when astronomers using the Kepler satellite to find earth-like planets around other suns told their fellow astronomers they were holding back the most promising data, those fellow astronomers reacted as though someone sequestered the ice cream.

In the olden days an astronomer with a telescope looked at his – and yes, it was likely to be “his” – stars and galaxies, took data on their brightness, size, color, distance, and published his wondrous discoveries and put the data in his closet. That proprietary attitude toward data changed a little toward the end of the 20th century, when new telescopes began to be paid for by NASA, the National Science Foundation, and the American taxpayer. Any astronomer who didn’t have his own telescope could use these telescopes and work on his data privately for a year, but then he had to turn it over to the public. So by rights, since Kepler is a NASA-funded satellite that launched over a year ago, the Kepler astronomers should make all 700 cases for possible planets public. Instead, they announced that they’ll release 300 stars that look like they have planets, and keep the 400 of the best stars with the most earthlike candidates for another eight months. Continue reading

Seldom has something so tiny and so unprepossessing exacted such an immense toll of human misery. Plasmodium falciparum, the protozoa that causes the most serious form of malaria, looks like a little red comma or pear-shaped stain on the surface of a red blood cell. Yet make no mistake, this tiny protozoa is a deft killer. In the list of the world’s deadliest infectious diseases, malaria currently ranks fifth, and each year between 1 to 2.7 million people–mainly pregnant women and children–perish of the scourge.

Seldom has something so tiny and so unprepossessing exacted such an immense toll of human misery. Plasmodium falciparum, the protozoa that causes the most serious form of malaria, looks like a little red comma or pear-shaped stain on the surface of a red blood cell. Yet make no mistake, this tiny protozoa is a deft killer. In the list of the world’s deadliest infectious diseases, malaria currently ranks fifth, and each year between 1 to 2.7 million people–mainly pregnant women and children–perish of the scourge.

Epidemiologists studying this nasty disease have long searched for its origins, since this data could offer clues for battling P. falciparum. Many researchers have looked to sub-Saharan Africa, suggesting the disease first emerged there some 6000 years ago when early farmers began clearing forests and creating lots of small sunlit basins of stagnant water–breeding grounds for mosquitoes carrying P. falciparum. The large villages of the time, moreover, were thought to have offered a plentiful supply of new hosts for the parasite. Human beings are the only reservoirs for malaria.

But archaeologists have never been keen on this theory: there’s little evidence of agriculture in Africa 6000 years ago. Now a very cool new study in Current Biology by Kazuyuki Tanabe, a biologist at the Osaka Institute of Technology in Japan, and his colleagues, sheds important new light on the matter. It turns out archaeologists were right to be skeptical. Malaria emerged at least 60,000 years ago in Africa, and accompanied modern humans on their momentous journey out of Africa. Continue reading

The elegant Eirene Gown, named for the Greek goddess of peace, is sewn from silk hand-gathered from naturally-hatched wild silkworms and woven on antique looms in a small mill in India. Its delicate coral hue is derived from a dye extracted from the root of the Madder plant, growing in a war zone in the high valleys along the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan. Chevron-shaped appliqués along the neckline come from the discarded part of the shells of the Mabe pearl, gathered and turned into jewelry by women of the Zanzibar Women’s Shellcraft Cooperative. Estimated price tag for the dress: between $3000 to $6000.

Top Shop it ain’t, and it ain’t on sale either: designer Katie Brierley, who produces her Isoude collection “in a slow and sustainable manner,” created the frock for the Fashion Institute of Technology’s new exhibition, Eco-Fashion: Going Green, on show until November 13, 2010. The antithesis of easily-tossed togs on sale in cut-price clothing stores, the Eirene gown is one of more than 100 garments and accessories in the New York exhibition.