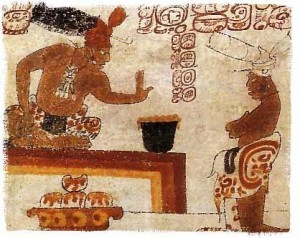

In the early 8th century A.D., the great Maya city state of Tikal reached the zenith of its sophistication and power. Its kings sipped frothy chocolate and smoked elegant cigars in their chambers, listening to the music of trumpeters and drummers. Its painters rendered brilliant court scenes on vases. Its architects designed pyramidal masterpieces that climbed to the sky. Tikal was the Manhattan of its day.

Over the next century and a half, however, the bloom went off the rose in Tikal. Its ambitious building program collapsed and its artists ceased to carve inscriptions on stone. Its divine kings vanished and its population thinned to just 20 percent of its peak. Tikal, moreover, was not the only Maya city state to suffer such a dramatic fall from grace. Elsewhere in the Maya world, dozens of other splendid cities crumbled over a span of 300 years ending around A.D. 1050.

Archaeologists have pointed to many reasons for the fall of the classic Maya civilization. The Maya slashed and burned most of their forests. They mined the fertility of their fields and allowed their populations to soar unchecked, straining food supplies. Then they fought wars over prized resources, terrible wars. When climate change finally arrived in the 8th century, in the form of severe, prolonged droughts, many Maya were singularly ill-equipped to weather it.

Just how did the Maya react to this sudden disastrous change in climate? Continue reading