This picture is what the sky really looks like. Click on it. It’s the biggest digital color picture of the sky, the part called the Northern Galactic Cap, and it’s taken years to produce; it’s a trillion pixels, a terapixel and — says the press release from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey — to see it at full resolution, you’d need 500,000 high-def TVs. In it are millions of asteroids, stars, quasars, and galaxies and they’re all free, go download them. It holds, says an astronomer who worked on it, “one of the biggest bounties in the history of science.” The camera that made the picture possible, a faithful and delicate and nearly perfect instrument, is now old news; it’s gathering dust, is out to pasture. Continue reading

This picture is what the sky really looks like. Click on it. It’s the biggest digital color picture of the sky, the part called the Northern Galactic Cap, and it’s taken years to produce; it’s a trillion pixels, a terapixel and — says the press release from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey — to see it at full resolution, you’d need 500,000 high-def TVs. In it are millions of asteroids, stars, quasars, and galaxies and they’re all free, go download them. It holds, says an astronomer who worked on it, “one of the biggest bounties in the history of science.” The camera that made the picture possible, a faithful and delicate and nearly perfect instrument, is now old news; it’s gathering dust, is out to pasture. Continue reading

For decades, the oceans were an overlooked domain when it came to environmental awareness. Extinction, it seemed, was something that happened on land and pollution, primarily anyway, was a fate for air, lakes and rivers. That was observation bias, of course: we spend most of our time on land, breathing air and drinking fresh water, so naturally we noticed those befoulments first.

For decades, the oceans were an overlooked domain when it came to environmental awareness. Extinction, it seemed, was something that happened on land and pollution, primarily anyway, was a fate for air, lakes and rivers. That was observation bias, of course: we spend most of our time on land, breathing air and drinking fresh water, so naturally we noticed those befoulments first.

No longer. Tales of oceanic woe wash ashore with great regularity now, but few can match the media splash made by plastic pollution, most famously in the form of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Imagine: A floating, Texas-sized island of wildlife-choking trash bobbing menacingly smack in the middle of the North Pacific.

The garbage patch media event has already contributed to plastic bag bans in San Francisco and elsewhere, and has both led to and been reflected in the improbable spectacle of at least two different awareness-raising voyages in vessels constructed of cast-off plastic water bottles, complete with a clownish battle over rights to the ship’s name “Plastiki.” Even Oprah Winfrey joined in, calling the Great Pacific Garbage Patch “the most shocking thing I have seen.”

Does it matter then that it isn’t the size of Texas, and isn’t a floating island of trash or even, really, a patch?

In the late spring of A.D. 793, British peasants experienced their first taste of Viking warfare, a clash so terrifying that it seemed to be of supernatural origin. “Terrible portents appeared over Northumbria and miserably frightened the inhabitants: these were exceptional flashes of lightning, fiery dragons were seen flying in the sky,” noted one scribe. “A little after that, in the same year on 8 June, the harrying of the heathen miserably destroyed God’s church in Lindisfarne by rapine and slaughter.”

In the late spring of A.D. 793, British peasants experienced their first taste of Viking warfare, a clash so terrifying that it seemed to be of supernatural origin. “Terrible portents appeared over Northumbria and miserably frightened the inhabitants: these were exceptional flashes of lightning, fiery dragons were seen flying in the sky,” noted one scribe. “A little after that, in the same year on 8 June, the harrying of the heathen miserably destroyed God’s church in Lindisfarne by rapine and slaughter.”

The Vikings, it seems, didn’t play by British rules of engagement. Continue reading

Scientists know a lot about infectious diseases. But a new study in the Archives of Internal Medicine finds that the treatment guidelines created by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) are based on imperfect evidence. Only one in seven treatment recommendations relied on evidence from a randomized controlled trial, the gold standard in medicine.

Scientists know a lot about infectious diseases. But a new study in the Archives of Internal Medicine finds that the treatment guidelines created by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) are based on imperfect evidence. Only one in seven treatment recommendations relied on evidence from a randomized controlled trial, the gold standard in medicine.

In a randomized trial, participants are randomly assigned to one of two groups—the “treatment” group or the control group. The control group receives the standard of care, say ibuprofen for a headache. The treatment group receives whatever new-fangled drug or intervention the researchers want to test, say meditation or Valium.

At first blush, this apparent lack of high-quality evidence may seem like cause for outrage. But ask any medical researcher, and they will tell you that clinical trials are crazy expensive. In some cases, they aren’t even possible. And in other cases, they’re just plain stupid: We don’t need a clinical trial, the authors point out, to tell us that staying far away from ticks cuts our risk of contracting Lyme disease, nor do we need a clinical trial to tell us that nurses and doctors should wash their hands to prevent the spread of infections. Continue reading

The older I get, the more people I know who have lost what they could not afford to lose. I’ll repeat: lost means gone, unrecoverable, not coming back; and what these people lost, they still need and want. The problem is nearly universal and has no obvious solution, or rather, the solution is idiosyncratic and not necessarily found by looking. Somehow it just, more or less, sorts itself out. Meanwhile, daily life must be slogged through as gracefully as possible, looking as normal as possible, staying on the surface. Otherwise you won’t get invited to dinner parties. Geophysicists have an inelegant phrase, “mantle drag.” Continue reading

The older I get, the more people I know who have lost what they could not afford to lose. I’ll repeat: lost means gone, unrecoverable, not coming back; and what these people lost, they still need and want. The problem is nearly universal and has no obvious solution, or rather, the solution is idiosyncratic and not necessarily found by looking. Somehow it just, more or less, sorts itself out. Meanwhile, daily life must be slogged through as gracefully as possible, looking as normal as possible, staying on the surface. Otherwise you won’t get invited to dinner parties. Geophysicists have an inelegant phrase, “mantle drag.” Continue reading

One of our favorite science writers has just published a terrific new book, The 4% Universe: Dark Matter, Dark Energy, and the Race to Discover the Rest of Reality. So I nabbed author Richard Panek, who just happens to be an LWON blogger, for a Q and A session.

One of our favorite science writers has just published a terrific new book, The 4% Universe: Dark Matter, Dark Energy, and the Race to Discover the Rest of Reality. So I nabbed author Richard Panek, who just happens to be an LWON blogger, for a Q and A session.

Q: Your book’s really provocative. What first drew you to the subject?

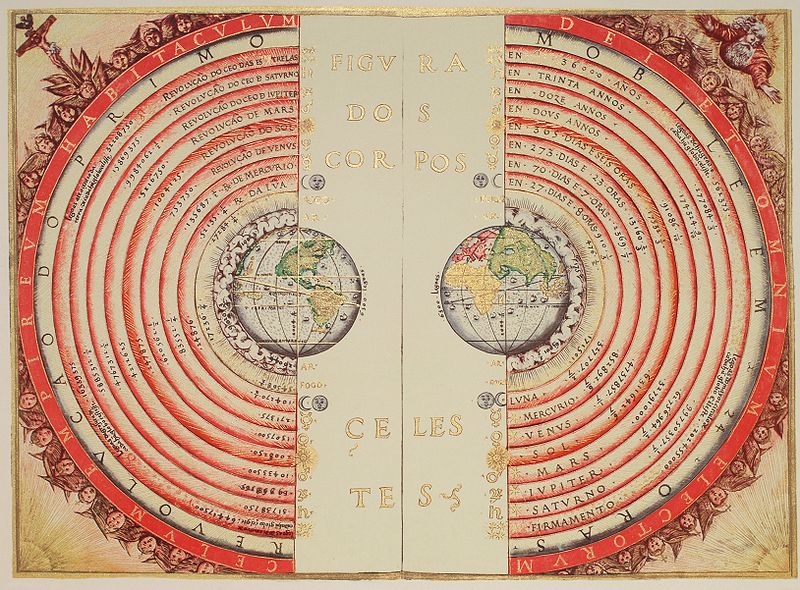

A: The central idea—that what we’ve always thought was the universe in its entirety, for thousands of years, is only 4% of what’s actually out there—is absolutely wild. When I first heard about this idea at astronomy conferences about ten years ago, I thought it was too wild to be true.

We lost one of the grand patrons of the nerdy childhood this past week. Milton Levine—Uncle Milton to you—sold his first Ant Farm in 1956, launching a mail-order formicarium empire and inspiring, for a time at least, millions of junior entomologists. I made do with older ant-watching techniques, spending countless childhood summer hours belly-down on the sidewalk behind our garage, nose-to-mandible with the red ant colonies that thrived there.

We lost one of the grand patrons of the nerdy childhood this past week. Milton Levine—Uncle Milton to you—sold his first Ant Farm in 1956, launching a mail-order formicarium empire and inspiring, for a time at least, millions of junior entomologists. I made do with older ant-watching techniques, spending countless childhood summer hours belly-down on the sidewalk behind our garage, nose-to-mandible with the red ant colonies that thrived there.

I was fascinated by their busy digging, and both alarmed and thrilled by occasional gruesome spectacles. I remember thinking how like Paleolithic mammoth-hunters the scores of ants subduing and dismembering a vastly larger caterpillar seemed, unable to look away as the creature writhed and squirmed under the ants’ devastating, coordinated attack.

The more advanced ant observer will eventually encounter all manner of human-like behaviors, from weaving (nests, in trees) to farming (fungi, underground) to herding and “milking” other animals (aphids, disgusting). But by far ants’ most anthropomorphous characteristic is the facility with which they go to war with their neighbors. Continue reading

There are many ways to celebrate a new year—for me, it’s by becoming a “person of LWON” and joining some of my favorite science writers at this commodious corner of the web.

For fishmongers at the massive Tsukiji market in central Tokyo, however, there’s no more festive way to ring in the New Year than with the first bluefin tuna auction of the season. That happened on Wednesday this year, with the first fish selling for an unprecedented $396,000. Some are calling the record price auspicious—surely $1000-per-kilo fish must be a sign of recovering luxury markets in Japan and China.

At 324 kilograms, this tuna was a relative welterweight—the largest Pacific bluefin can weigh 450 kilos. But the first sale of the year is considered especially lucky, and delivers a guaranteed PR boost for the winning bidders, in this case owners of upscale restaurants in Tokyo and Hong Kong. But there’s a distinct rummy whiff to this kind of luck. Continue reading