My dad’s 100th birthday would have been this weekend. 100! It seems incredible—so many years since 1923, so many things that happened in them. How different it must have been, how many things might have been not so different at all.

These are the things I think I remember that he told me: behind his house there was a pond that had goldfish, and then there was a cat, and there weren’t so many goldfish anymore. The Great Depression happened; they ate canned things. Creamed beef, soggy corn. We had a wooden sewing stand that was filled with buttons that maybe his mother, or maybe her mother, had saved.

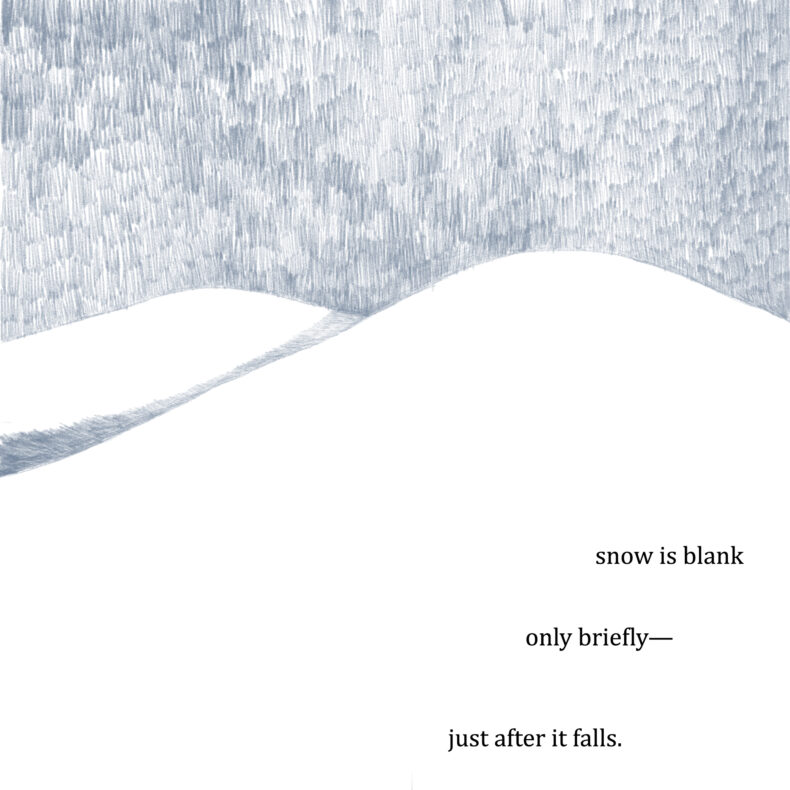

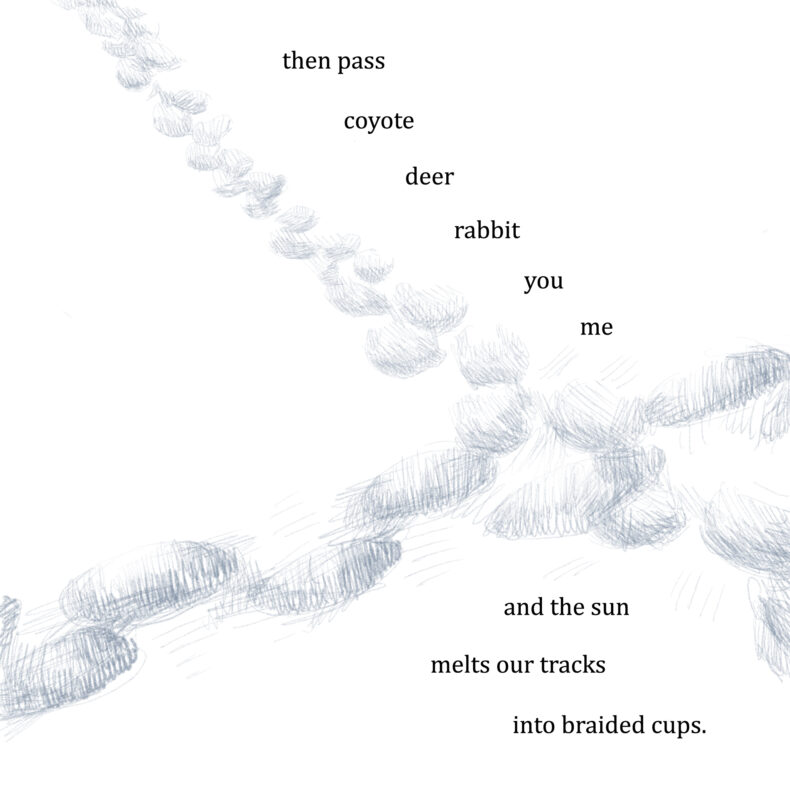

At school, his favorite class was Latin and they sometimes went skiing over a golf course after it snowed. He went to college somewhere his parents wanted him to go but he didn’t. He worked at the newspaper. He worked as a hasher at a sorority house. After a while, he dropped out. No one knew where he went.

Months later, he resurfaced in Chicago. He considered being a minister. He started studying to be a lawyer. Then the war started. He considered being a conscientious objector. Something changed. He went to boot camp, he studied languages. He went to England. Once the war was over, he went to Austria and maybe Germany.

He didn’t talk much about the war. He said that it’s the reason why he never drank coffee (it was terrible!) and rarely drank beer. He didn’t lose his love of languages. There was a period where instead of reading a bedtime story, he read from a Finnish exercise book. I remember words with a long “oo” sound.

One New Year’s Eve I was in Munich, and I called home because the truth was, New Year’s Eve in Munich was not as fun as it might sound. He seemed talkative: He told me that he’d been there, that he’d liked that city, and then he told a story that I’d never heard before about crossing a bridge in a jeep somewhere in Austria. The bridge collapsed right after. I am not sure if I imagined that. He still had nightmares, imagining that he’d killed someone.

A few years ago, some of the Army records got declassified and my mom sent away for them. There weren’t stories about jeeps and bridges, or codes he’d cracked, or locations that he had been that we’d never known, or the mystery of those missing months. But some of his personnel files had notes that revealed a person neither of us had known: my father as a young man.

Slender, health good. Fairly nice looking kid. Extremely alert; eye for detail . . . A clean cut chap; sense of humor, but amusingly serious. Says he’d like to try cryptography.

. . . quiet but with a wry and amusing personality. Extremely conscientious, takes the world serious but with a grin. Can be fully depended on in any situation . . . Is young and often shows it in his actions, but should not be dismissed as irresponsible.

There’s something sweet to me about these notes. Maybe that it’s these Army men—I’m assuming they were men, writing in a cursive scrawl and thick typeset—saw something about my dad that would remain true half a century later.

A hundred years after he was born, I still like to imagine what he’d be doing today. Well into retirement, he was still taking on odd jobs: dog walking, taxes, testing voice recognition software. The rest of this thought the whole thing was ridiculous—the program could hardly understand anything, and it was so slow! Who would ever use it?

He would cut out newspaper articles and send them to me: financial advice, Peanuts cartoons, career ideas. One of them about this program where you could learn to write about science—after all, I liked biology and I liked writing. I thought it was dumb. I was going to be an engineer! A doctor! An anything else! Another time when I was wrong.

Now I can imagine forwarding me links, taking blurry photos, using Siri to send his grandchildren messages.

He would love emojis. Love emojis. I even try to think of messages he would send: unicorn, computer, potty mouth. Plant sprout, upside down face, crying laughing, dollar sign, smiling devil. Pumpkin, rockstar, mermaid, frozen yogurt in a cone. He would have the patience to endlessly debate the kid who leads with their mind. Cat face, tsunami, mind blown. He would sit and listen to the one who leads with their heart. Palette, fencer, croissant, sparkle stars. He would marvel at the one who is in constant motion. Disco dancer, firework, poop face, starry eyes.

And I know what I would send back: 100. 100. Heart heart heart.