If you have been at LWON for a while, you might have noticed that I post this one every year–because somehow, once again, it is June. And once again, it is gloomy. But things have been extra-cloudy this year, and people who don’t live in California have noticed! I mean, the Washington Post was even lamenting our gloom, so you know it’s been bad, with a solid month of fog in May and even some unseasonal rainstorms. (If you’re feeling too gloomy to read this post, there’s a charming explainer of how June Gloom works from the LA Times.)

But things are looking up. July will reportedly be flush with sunshine and even heat. Now, about those wildfires . . .

*

I used to think the weather was something adults talked about because they were boring. And now that’s me, commiserating with neighbors about the state of our sky, which gave us a glorious, bluebird May and then rolled out a thick cloud carpet on the first day of June.

June Gloom isn’t just a Southern California phenomenon, and it doesn’t only happen in June. But perhaps we give it a name (and May Gray, and, in dire situations, No-sky July and Fogust) because we complain about it the most. The response from an Oregonian friend who visited this week: “Talk to the hand.”

(When I later looked at the Wikipedia entry for June Gloom, the authors concurred: “A similar phenomenon can occur in the Pacific Northwest between May and early July, though the phrase “June Gloom” is not nearly as commonly heard as it is in California due to the frequency of cloudy or overcast weather throughout the year in the Pacific Northwest.”)

Sam Iacobellis at Scripps Institution of Oceanography talked me through how SoCal’s gloom works. Different parts of the coast offer their own complications, but generally speaking, the cold Pacific water—aided and abetted by the California Current and the upwelling—and a high pressure region, the Pacific High, conspire to form the marine layer clouds that some of us call gloom.

Usually, the atmosphere gets colder as you head up. But the cold water creates a situation where the air near the water’s surface is colder than the air above it: an inversion. The Pacific High pushes air downward, compressing it and warming it. Together, this forms a stable inversion air that can hold a layer of cloud near the water’s surface like an older brother crouching on an upstart sibling.

Gloom often dissipates in the afternoon, as sunshine warms air near the surface. The warmer air mixes into the clouds and starts to break them up.

Of course, there’s a lot more than that going on, too. The gloom is the home of a wild kind of cloud field called actinoform clouds, which, to a satellite’s eye, look like enormous leaves or pinwheels. And the ocean itself might be providing more than just cold water. Iodide released by kelp may turn into cloud condensation nuclei, which could make clouds thicker and more pervasive.

All this fascinating stuff doesn’t prevent me from being boring. But I also think I was a bit too harsh on weather as a conversational topic. Yes, it is something to talk about when there’s nothing left to say. Yet it’s also a shared experience that has the potential to affect everyone.

When someone I don’t know very well says, “this weather is making me crazy,” I feel like I really do understand, more than if she talked about how her kids or parents or work was setting her teeth on edge.

Weather connects me to other times, too. I can imagine the Chumash, who lived on this coast long before the rest of us showed up, standing on the bluffs when the clouds start to break up. Those first rays of sunshine feel so needed that it almost feels like my skin is consuming them; I wonder if one of them felt this way, too.

Even when the gloom doesn’t lift all day, there are ways to enjoy it. There’s a contest that’s been going on for the last ten years or so among a few Scripps employees to guess the number of gloomy days in May and June.

I asked if there was any trick to forecasting gloom. Events that affect sea surface temperature, from the El Niño/La Niña cycles to the Pacific Decadal Oscillation may play a role in the amount of gloom. Iacobellis says the contest is really a crapshoot, but it also has a way of making the gloom seem less gloomy. Each cloud-covered day is one step closer to victory.

Each gloomy day, too, is a chance to think about what’s happening out there: cold water, enormous swirls of clouds, that lunk of an inversion layer pinning the gray above our heads. Watch out, neighbors, here I come. And now I have even more to talk about.

Today’s playlist: Crowded House, Weather With You; Len, Steal My Sunshine; The Like, June Gloom

***

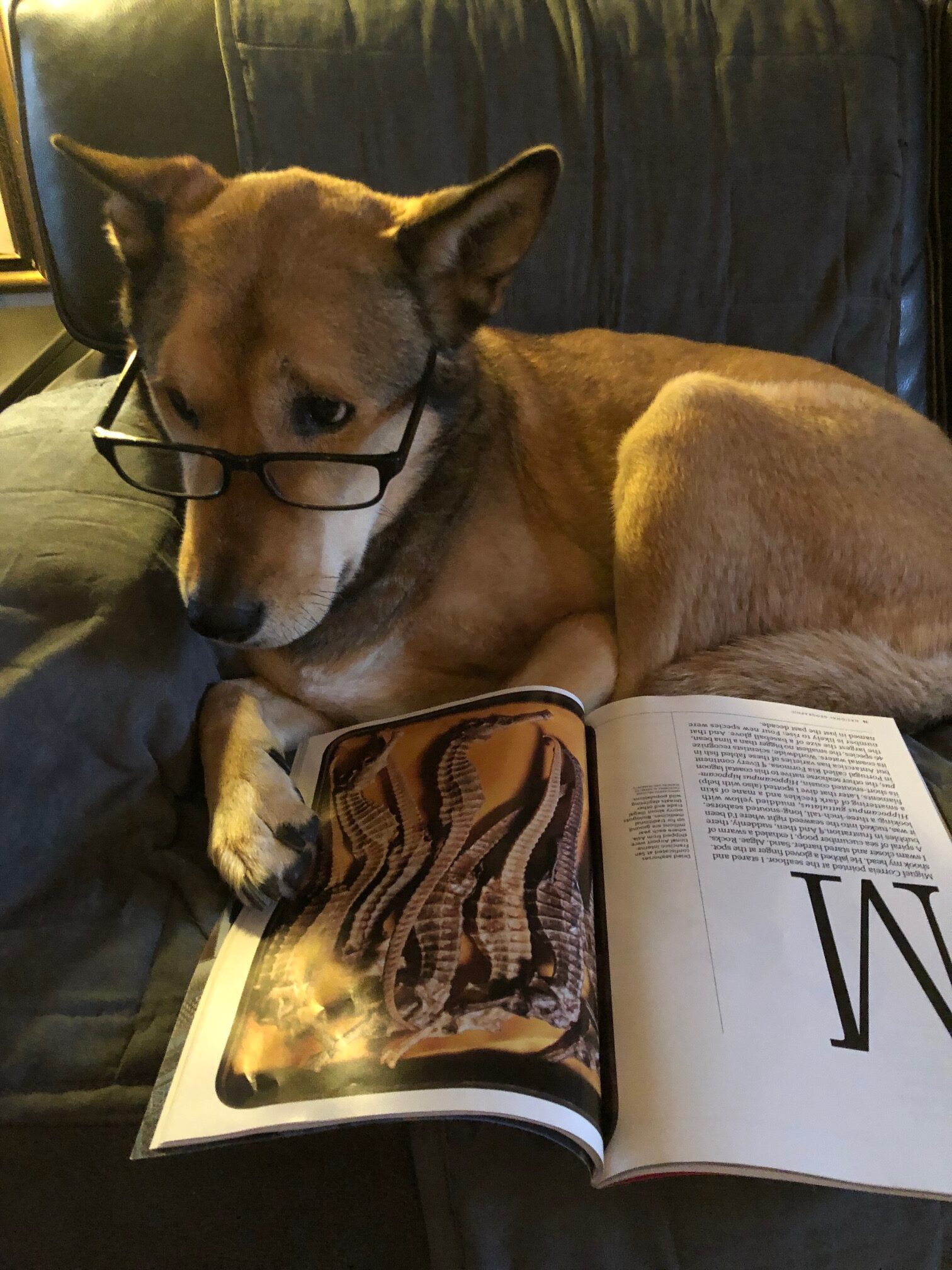

Images Top: Eric Gangnath Middle: marya Bottom: Steve Lyon