It began with a software engineer in India. The man’s email signature says that he works in “Dreams Sustainment (Offshore).” His note with the subject line “Regarding INC5760131” referred to some technical issue that was virtually incomprehensible to anyone who was not among the email’s intended recipients. And there were a lot of unintended recipients. Somehow this poor guy managed to copy everyone working in ESPN content.

That’s a lot of people. ESPN employs about 8,000 people worldwide, and during a single short burst that morning, his misdirected email spawned something like 138 replies. I know this, because I worked for ESPN and was on the receiving end of the email tsunami.

The NC5760131 fiasco was no isolated incident. In 2012, an NYU student accidentally sent a query about his tuition payment to 39,979 other students. Time Inc and Reuters have also suffered reply-all incidents, but these incidents are nothing compared to a test message sent to UK’s National Health Service’s 1.2 million members, which created a deluge of emails so big that it crashed the system.

“Regarding NC5760131” wasn’t my first involuntary ride on a reply-all train. Not long before that email thread clogged my inbox, I found myself copied on an email thread about Kay’s hip surgery. I still don’t know who Kay is, but it seemed that her surgery had gone well, and the other 28 people on the thread were eager to congratulate her. I would have just deleted these emails and set up a filter to send them directly to spam, but once I started reading these notes, I couldn’t stop.

Over the course of Kay’s long email thread, I listened to a member of the group agonize over whether to return home (wherever that was) after a stint in Australia. I also received news of Tom’s tragic and untimely death. I read heart-felt memories about Tom and his friends, and it felt something like dropping into a soap opera a few episodes into season two. Eventually I surmised that this group of women had been high school classmates. I couldn’t bear to tell them that they had accidentally invited a voyeur into their midst. But I also knew that asking them to take me off their list was likely to just spark even more emails.

Which gets me to my Ann Landers question. What do you do when someone erroneously copies you on an email thread? The answer is simple. Don’t engage. A concise New York Times Q&A from 2016 was published with the headline “When I’m Mistakenly Put on an Email Chain, Should I Hit ‘Reply All’ Asking to Be Removed?” The one word answer? No.

It’s not the content of the email (in most cases) that makes a reply-all thread so annoying, it’s that it exists at all. Which is why replying only amplifies the awfulness. The best thing you can do in response to a reply-all thread is nothing. Let the damn thing die.

If only people would. Consider the NC5760131 thread. I put 136 of the emails (the ones that my spam filter didn’t eat) into a spreadsheet to analyze how the thread played out.

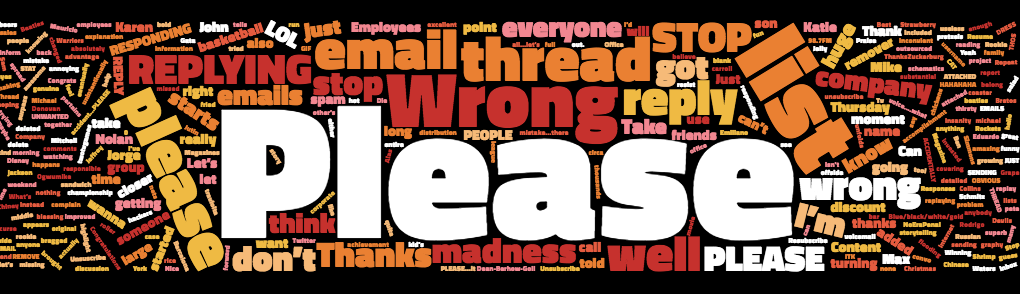

The first replies were earnest. “I think you added me to this email thread by mistake,” someone wrote. Within minutes, a new meme emerged. “Sorry, wrong [David or Karen or Chris]” replied some of the first responders. (“Wrong [insert name here]” became an ongoing joke as the thread expanded.)

Here’s my rough count of the overall responses. (They add up to a few more than 136, because some replies fell into multiple categories.)

48 jokes about the thread

31 requests to unsubscribe from the email chain

19 replies reveling in the absurdity of the reply-all thread

17 emails explaining the problem (“I think it’s obvious we were all accidentally attached to the email”)

14 replies saying “you’ve got the wrong [insert name here]”

10 photo memes (for instance, a photo of Michael Jackson eating popcorn with the words “I just came here to read the comments.”)

8 instructions: here’s what to do and how to stop replying to all. (“Please don’t reply all,” one person wrote, adding a long, detailed explanation.)

6 desperate attempts to make the emails stop, with exclamation points, all caps or other cries for help (STOP REPLYING ALL!!!, one person wrote.)

As you can see, the jokes outnumbered the earnest replies, and this was especially true as time went on and the LOL replies eclipsed the serious ones. Early in the thread, which lasted less than two hours, someone sent this plea:

PLEASE…it was a mistake…there are thousands of people on this email by accident…PLEASE don’t everyone reply all…let’s end the madness now before it starts!!

I chuckled when I read that. How naive to believe that such madness can be stopped. Once something’s on the internet, it takes on a life of its own. As the NC5760131 emails continued, they became more and more light-hearted. “I just wanted to inform the group that a hot dog is 100% a sandwich,” wrote one guy. Of course there were GIFs, and it was probably inevitable that someone posted a photo of The Dress. Sub-threads developed, with people making pitches for their favorite sports team (“Let’s go Mets!”) and ridiculous self-promotion (“Now would be a great time for all of you to take advantage of ESPN The Magazines discount for employees, friends and family.”) One guy even attached his resume, perhaps hoping to upgrade his job.

The thread eventually ended when someone from corporate intervened to block the thread. But don’t tell that to the guy who sent the last reply. His earnest note explained what was happening and asked “Please use this tool (email) in a responsible way.” He probably thinks it worked.

___

This post first ran on April 25, 2018.