This week was devoted to being Off Our Meds, looking calmly and as rationally as possible at scary issues in medicine.

Ebola is about as bad as it gets, and no vaccines or drugs. Guest Robin Mejia suggest we learn some R numbers: “for each day that we’re not effectively isolating people . . .the job of stopping the outbreak, turning it around, gets much bigger and much, much more difficult.”

Sometimes, says Erik who’s a cradle Christian Scientist, the placebo effect, which everybody says is powerful but nobody knows how it works, might just be a doctor and patient talking to each other.

Do you want to know a diagnosis that’s uncertain? do you want to await certainty? and what’s your doctor supposed to do about this? Cassie tells the most godawful story, commenters argue with her.

Richard got very sick. Doctor was seen, tests were done, hospitalization was had, doctor seen again: “Finally, he spoke: ‘Medicine is an art, not a science.’ Screw you, bub. I’m the writer here. You’re the empiricist. So let’s go: What’s the diagnosis?”

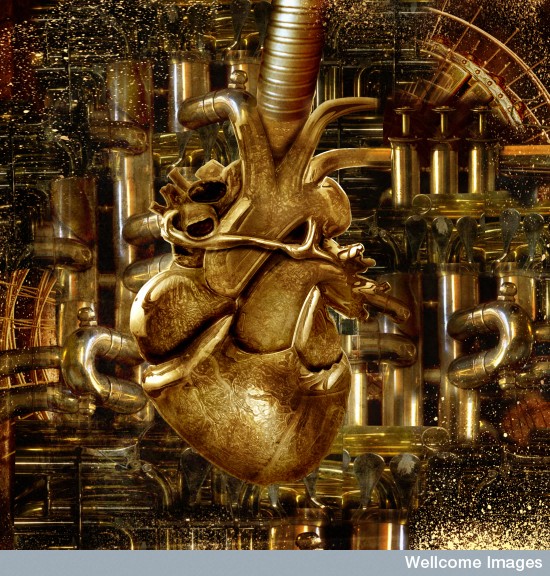

Guest Colin Norman retired, then decided to stop ignoring his family history, then began his medical education. In the last post of the series Off Our Meds, and the first post in the series Affair of the Heart, he takes us with him. Next in the series is this Monday.