Time for another visit from Bad Science Poet. Remember: “It’s not the science that’s bad—it’s the poetry!”™

Time for another visit from Bad Science Poet. Remember: “It’s not the science that’s bad—it’s the poetry!”™

A LESSON IN HUMILITY FOR SCIENTISTS

Bunsen had a burner.

Ike had Tina Turner.

And which became president?

Time for another visit from Bad Science Poet. Remember: “It’s not the science that’s bad—it’s the poetry!”™

Time for another visit from Bad Science Poet. Remember: “It’s not the science that’s bad—it’s the poetry!”™

A LESSON IN HUMILITY FOR SCIENTISTS

Bunsen had a burner.

Ike had Tina Turner.

And which became president?

This is the third post in Affair of the Heart, a series that takes place at the intersection of a highly-experienced science writer and the medical system.

by Colin Norman

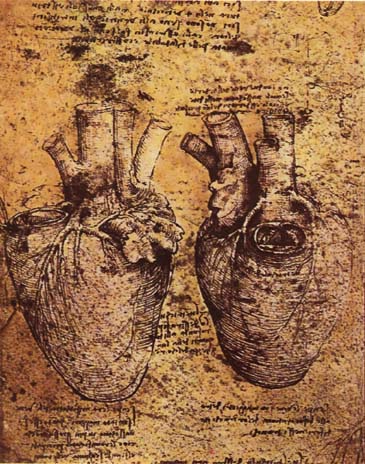

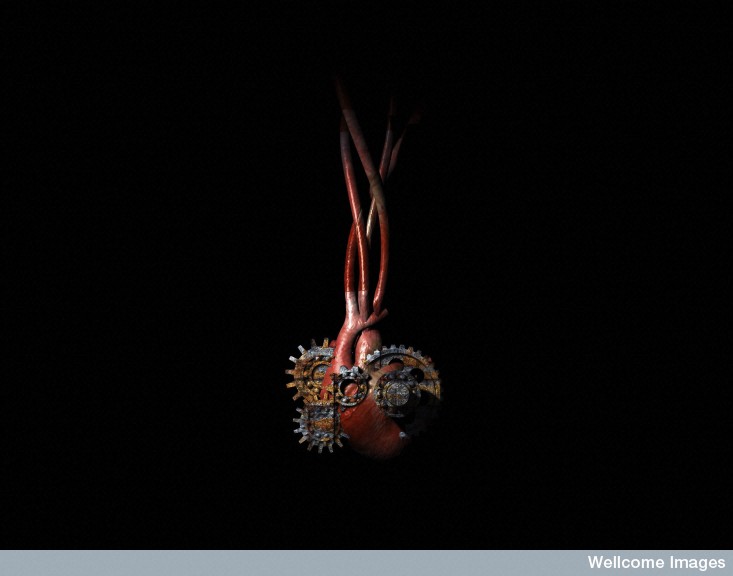

When my aortic aneurysm could no longer be ignored, and my cardiologist recommended a consultation with a specialist, I finally began to act like a science journalist.

When my aortic aneurysm could no longer be ignored, and my cardiologist recommended a consultation with a specialist, I finally began to act like a science journalist.

I scanned the literature and called medical experts and physician friends, who put out feelers to others in the medical profession. I got some reassuring responses: There are several excellent centers and surgeons who specialize in repairing diseases of the aorta. Among them is Duke Cameron, chief of cardiac surgery at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore. Johns Hopkins is a national center for the study and treatment of Marfan syndrome, a genetic disorder characterized by, among other features, long limbs and a predisposition for aortic aneurysms. Duke Cameron has probably seen more aortic aneurysms than almost any other surgeon in the world. He sounded like the man for the job.

My wife Anne and I first met Dr. Cameron on a Saturday morning in April. He had had to cancel an appointment earlier in the week because he was sick, and came in on Saturday to see me and another patient in the otherwise empty cardiology offices. It was a good sign. A calm man with a reassuring demeanor, he certainly didn’t fit the stereotype of the swashbuckling heart surgeon. We liked him immediately. Continue reading

October 13-17, 2014

Colin Norman continues his exploration of the medical system through his own familial cardiovascular condition, and Cameron finds a universe in a small window pane.

Michelle celebrates the day now dedicated to Ada Lovelace, patron saint of gifted women.

A midnight encounter with a beaver leaves Chris Arnade in a standoff between cuteness and destructive nuisance. He takes the only logical way out: the Way of the Assassin. I organize a conference on traditional knowledge, TED-talk style.

Image: Burgruine honberg fenster web by Sebastian Kirsche via Wikimedia Commons

In 1972, Chief Jimmy Bruneau of the Tłı̨chǫ First Nation attended the opening of the school that would bear his name. As part of the ceremony, many dignitaries got up to the microphone before him and gave long-winded speeches. Bruneau was an old man and very ill (he would die three years later), so when his turn came, he told the crowd he would only be able to speak for a short time.

In this short speech he laid out the plan for a new educational system that would see native youth become “strong like two people” – with confidence both in the wage economy and in traditional skills. His vision was so clear and powerful that it formed the basis of much of the Tłı̨chǫ territory’s direction for the next 40 years.

In the local language, this speech is known as Įłàà Katı̀, or “few words with much meaning”. When I began to work with a team organizing a conference on traditional knowledge and its place in the modern world, we realized that Chief Bruneau’s address on the topic was akin to the present-day TED talk. We decided to invite anthropologists from around the world to speak about traditional knowledge – heretofore a fairly inaccessible, complex and long-winded field – in 17-minutes or less. Continue reading

I have a beaver, which I am going to kill, which is a complex thing to do. The beaver moved into a small pond on my property a month after I moved from Brooklyn. I came 100 miles, the beaver had to move less than a mile, coming from wetlands that border part of my property. Beavers are not known to travel much more than that.

I have a beaver, which I am going to kill, which is a complex thing to do. The beaver moved into a small pond on my property a month after I moved from Brooklyn. I came 100 miles, the beaver had to move less than a mile, coming from wetlands that border part of my property. Beavers are not known to travel much more than that.

The pond is small and roughly rectangular, about half an acre. Two of its sides are ringed with trees. Those sides are where the action is. Frogs, snakes, voles, mice, birds, raccoons, and hedgehogs fight for room.

Two weeks ago, near midnight, I was photographing frogs on the pond’s edge, sitting under a bright moon. The beaver announced itself with a loud slap of its tail on the water, a sound I mistook for a bass jumping.

Two weeks ago, near midnight, I was photographing frogs on the pond’s edge, sitting under a bright moon. The beaver announced itself with a loud slap of its tail on the water, a sound I mistook for a bass jumping.

The sound repeated within a few minutes, only louder. Bass don’t jump like that.

The beaver was swimming across the pond, head out, its teeth reflecting in the light from my flashlight. It made five or six laps, staring straight ahead. Ok, beaver, I get it, you can swim fast. It then slipped under the water. Gone.

Beyond the beaver, floating in the middle of the pond, was a branch about fifteen feet long, still with the orange leaves of early fall.

Earlier in the day I had found a small tree, perhaps six feet tall, its trunk about 2 inches in diameter, lying across the footpath in the further woods that rings the pond. I cleared it away, confused that wind had knocked it down.

I had a beaver. I was content. This is why I had moved out of Brooklyn. Continue reading

At 3 a.m., a quiet settles like fog around the neighborhood, freckled by a few bursts of sound. Sometimes there’s the whistle of an incoming train. An acoustical trick might carry sea lion barks from distant buoys, the deep buzz of fishing boats, even a wave pummeling the rocks. Occasionally, a single too-loud bird call coughs and silences itself. I imagine that it’s a youngster, unable to stop from bursting into laughter, with its parents giving it the avian equivalent of the look that means pull yourself together right now or else. Continue reading

I’m not, in general, huge on holidays. I often wish that those of us in the U.S. would observe the weeks between Halloween and Martin Luther King, Jr., Day with a nice long nationwide nap. But I feel differently about Ada Lovelace Day, founded by British digital-rights activist Suw Charman-Anderson in 2009. Now, every year in mid-October, the world has a chance to recognize Lady Ada, the woman some call the first computer programmer.

I’m not, in general, huge on holidays. I often wish that those of us in the U.S. would observe the weeks between Halloween and Martin Luther King, Jr., Day with a nice long nationwide nap. But I feel differently about Ada Lovelace Day, founded by British digital-rights activist Suw Charman-Anderson in 2009. Now, every year in mid-October, the world has a chance to recognize Lady Ada, the woman some call the first computer programmer.

This year, Ada Lovelace Day arrives with a fine new Lovelace biography, Ada’s Algorithm: How Lord Byron’s Daughter Ada Lovelace Launched the Digital Age. The last major standalone biography of Lovelace was published in the late 1990s, and a lot has happened since then: a new set of letters between Lovelace and her collaborator Charles Babbage was discovered in 2000, and we’ve all clicked and poked and LOLed our way through another decade of the digital age. Ada’s Algorithm argues that Lovelace was one of the first—if not the first—to foresee just how deeply computing would affect our lives. Continue reading

This is the second post in Affair of the Heart, a series that takes place at the intersection of a highly-experienced science writer and the medical system.

A few months after my brother almost died from an aortic dissection, when his aorta began to break down right where it emerges from the heart, I was in the office of a respected Washington cardiologist to get myself checked out.

A few months after my brother almost died from an aortic dissection, when his aorta began to break down right where it emerges from the heart, I was in the office of a respected Washington cardiologist to get myself checked out.

He ordered a stress test, which I completed with no sign of any problems—I was a dedicated runner, after all. But when I asked him whether a stress test would indicate precursors to aortic dissection, he agreed it probably wouldn’t. That would require an echocardiogram—ultrasound imaging that shows the structure of the heart and aorta and, thanks to the Doppler effect, displays the flow of blood through the heart chambers and major blood vessels in hues of red and blue. It so happened that an echo machine was available in his office at that moment, so I had the procedure there and then. The cardiologist left to see another patient, saying he would be very surprised if the echocardiogram showed any abnormalities.

The next morning, however, he called to say the imaging had turned up something: a mild dilation of the aortic root. He prescribed a beta blocker, a drug that lowers blood pressure, slows the heart rate, and reduces the strength of the heart’s contraction, relieving some of the stress on the aortic root. And he recommended a follow-up echocardiogram in 6 months.

The follow-up echo apparently showed little or no change, and another one a year later also showed no further dilation. So I became complacent. I let the time between supposedly annual imaging stretch out a couple of years–or more. Continue reading