What follows is a poem about the Voyager spacecraft I wrote a long time ago, when the world and I were very different than we are today. For a multisensory experience, you can read along while listening to a splendid set-to-space-noise version here.

What follows is a poem about the Voyager spacecraft I wrote a long time ago, when the world and I were very different than we are today. For a multisensory experience, you can read along while listening to a splendid set-to-space-noise version here.

“Whether we like it or not, there are things out there, not alive, that think about us,” wrote a contributor on the internet anthropologist Katherine Dee’s substack. He was talking about the networks of technologies designed to stalk our movements and use the information to influence our decisions and command our attention.

In the age of these infinitely networked technological megafauna, how do you know if anything you are dealing with on the internet is under human control or driven by its own opaque desires? What is watching you? How will it act on the information it harvests?

I have begun to mentally categorise these nonhuman entities along the same lines theologians once taxonomised them in the old grimoires:

Continue readingI’m in my office. It is snowing lightly outside, and suddenly I hear them — a flock of sandhill cranes flying overhead. So I step outside for a moment to observe their formation and remember that the world is still a beautiful and wondrous place.

This realization is what is keeping me grounded amidst the alarming and increasingly dystopian news that keeps coming. Yes, I will stand up and fight as much as possible.

But I am also taking time to stop, breathe and listen. I filmed the video here (turn the sound up!) while skiing earlier this week. I noticed a sound, so I paused to look up and listen. The noise is so distinctive, a gentle trilling sound.

There is now a population of cranes that winter near here, but this time of year — spring — also marks the mass migration of larger populations who stop at Fruit Grower’s Reservoir on the South slope of the Grand Mesa on their migratory route. It’s a sign of spring, just as much as the apricots that are now blooming down the road from me. (I hope mine can wait a little longer, so as to avoid a freeze.)

Happy spring!

Spring seems to come every year. The apple tree in front yard has leaves. The season of direct sun in the living room: over.) Everyone else has started taking their dogs for longer walks. (The season of walking my dog in relative peace: over.) The trees shed their pollen and my nose runneth over. (The season of clear breathing: over.)

The famous cherry blossoms of Washington will reach peak bloom in the next few days, but in the meantime the non-famous trees of Washington are putting on a show. That apple tree will put out its pretty little flowers soon – I can see the buds from my desk. A neighbor’s dwarf peach (that’s the picture above) is putting on a show already.

I had more trouble than usual figuring out what to write about this month. So much is happening on so many fronts here in Washington these days that it’s hard to get your head around and exhausting, too. Too big to tackle in writing while I’m living through it. So I try to be grateful for moments of good news as I wait for peak bloom.

Photo: Helen Fields, obviously

I always knew flying squirrels lived among us, probably of the southern variety, in the trees at our cabin-in-the-woods in central Virginia. But those buggers are hard to spot. They’re night-owls, first of all, and they’re pretty small. So, I was delighted to see a whole nest of them in our woodshed this winter. (Okay, truth is my husband found them when I wasn’t there one weekend and bragged about his discovery, and I only got to see them by pics and video. Had I been there, I surely would have plucked one out of that nest and kissed it on its little velvety head, so perhaps it’s best I was elsewhere.)

When I saw there were numerous squirrels tucked into the nest together, I assumed they must be pups (also called kits, funnily enough) and thought, huh, why would they have babies during this cold, hungry season? Then I read that the adults commonly come together in the winter to stay warm; nests have been spotted packed with as many as 50 of the things. (This one had eight or ten.)

They don’t actually fly, of course; they have this flap of loose skin on each side of the body attaching fore leg to hind leg, and it creates an airfoil so they can glide in a downward direction (steering with their tail), usually 25 feet or so but sometimes more than 200, or so I’ve read. They have white bellies and pink ears and glorious huge eyes allowing them to see in the dark, all of which makes them extra cute. (Big eyes is one of those traits we humans especially love in other creatures, as it projects innocence and childishness and a request for love and care, in a way.)

Flying squirrels have an impressive repertoire of calls, more than any other type of squirrel, with some utterances out of the human range of hearing. If I’d actually been there with the nest I would have recorded these calls, but I wasn’t, so I couldn’t, so I’ll attach someone else’s recording of their chirps. (Scroll down to “Voice.”)

I’m hoping next time I’m at our cabin the nest is still there, overflowing with little warm bodies. At times like these when the world feels like its imploding, it’s comforting to find wild things living their lives as if nothing is wrong.

Photo by John Holland, that lucky duck

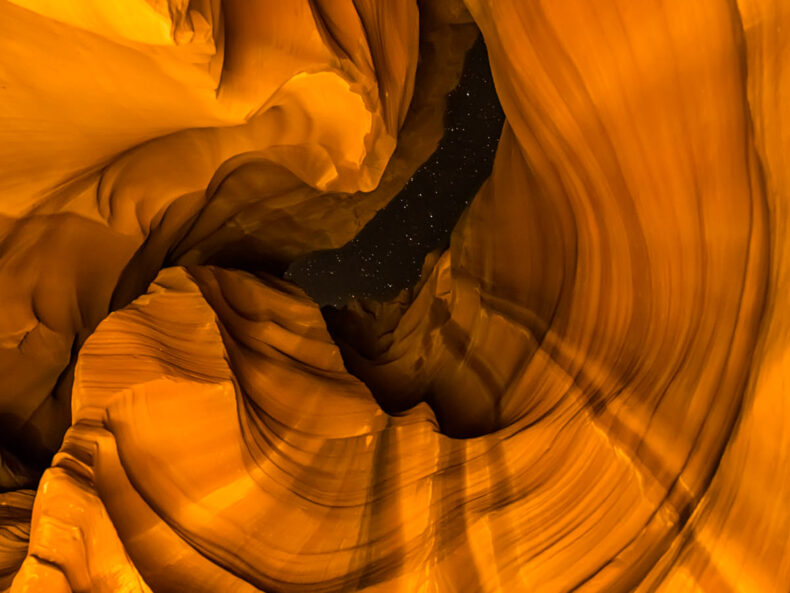

Decades ago when I was hoping to become a scientist, I got a master’s degree dealing with the actions of water in the desert, part of which was studying the hydrology of flash floods on unvegetated bedrock. One term for the result is a “slot canyon.”

When people died in a flash flood in a narrow canyon in Zion years back, NPR brought me on to explain what happened and why. I told listeners that these desert rainstorms touch ground far away and run fast over forty or fifty miles, finding people in a dry, sunlit cathedral dazzled by the convoluted walls around them, perhaps wondering what could have formed such a place. Water and debris arrive in what is called a “flood bore,” either a towering wave or a long, inescapable slope: ankles, knees, and once it’s to your waist you’re ass over teakettle. It keeps rising ten to forty feet or more, a maelstrom of mud, water, and boulders leaving a log jammed between walls sixty feet up in the air. No skill or strength can save you. Everything is up to the flood.

The best chance you have is scrambling to a high ledge when it hits, and hoping it’s high enough.

I interviewed workers on body recoveries, usually Park Service or land agency employees (those now being fired) telling me of a wedding ring being the only thing still on a man, or how three people were all swept together under a ledge miles from where they started as if the water took them in its hand. I was told about a person’s face like a mask, only the face, no bone or anything else. The flood seems to have some kind of agency. Anything in the way enters into the equation.

Continue reading

When civilizations fall into barbarism, the arising culture fetishizes strength. So it has always been. It can feel as if the weak and sensitive have no place and no voice in a time when throwing one’s weight around is the done thing.

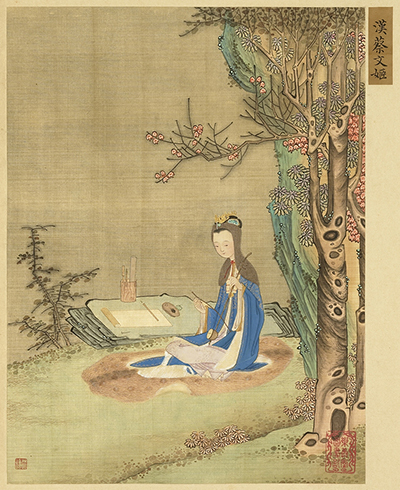

This was the world in which Cai Yan, a Chinese noblewoman at the end of the Han Dynasty (around 200 A.D.) found herself when her homeland was thrown into war. She was kidnapped by nomads and taken into the desert as the concubine of a chieftain. She says her captors had the practice of killing the old and weak, while idolizing the young and vigorous. By the time the Han Court negotiated her return, she had borne two sons whom she had to leave behind in the desert, never to see again.

Cai Yan is that rare phenomenon—a voice from the ancient female experience. She tells the story of her life in “18 Verses Sung to a Tatar Reed Whistle“, a lamentation with an interiority that feels ahead of its time. Though she had such little agency in a life dictated by men, there are glimpses in the poem of her power to assert herself in the world. One is her mention of her decision to raise her sons without shame, despite the circumstances of their birth. Another comes from the self-conscious reference to her own art: “As I sing the second stanza I almost break the lute strings / Will broken, heart broken, I sing to myself.”

I can imagine this woman, alone in a world of macho men, singing to herself in the nomad camp. But then I imagine another gentle soul picking up her melody on the wind, taking brief respite (as from the Cellist of Sarajevo). The whole poem feels like an act of resistance, and I find it fitting that her art is so compelling it has lasted for thousands of years while those who subjected her to violence and insults are lost to time. As deflating as it may be to create with posterity alone in mind, know that there may be others listening from neighboring tents, similarly despairing, taking heart from your humanity right now.

There is always one section in our utensil drawer that is emptier than the others. Spoons are useful for so many things, and they seem to have a natural restlessness. They leap away from the confines of the kitchen. They jump into cars and carry-ons. Sometimes the places they go are even stranger. All they need is for some piece of china to whisper “Hey, diddle diddle,” and there they go, sneaking out with the dish again.

In their absence, I have learned more about them. Spoons have, depending on who you ask, between four and seven parts. There is the bowl and the handle—the two parts I know the best, because I hold one part and the other one has the food in it. But there is also the neck, the shoulders, the drop, the tip of the bowl, and the tip of the handle.

Different types of spoons are paired with different purposes. A slotted spoon can strain beans and lentils, a ramen spoon helps you sip the broth and scoop your noodles. When you need a break from eating ramen, the bent tip of the spoon’s handle is like the shepherd’s crook that used to lean against the lifeguard tower, a tool for preventing your spoon from drowning. The name of a ramen spoon is chirirenge, a fallen lotus petal.

Continue reading