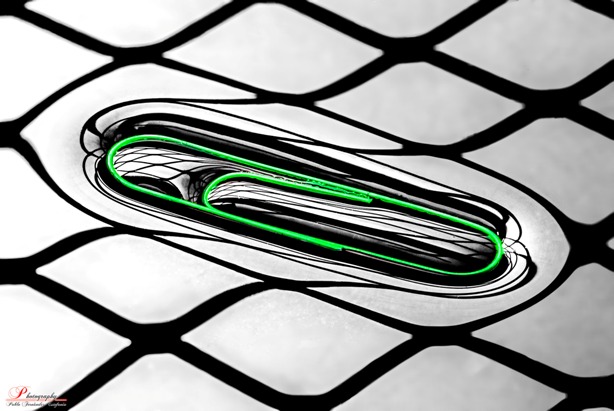

Not long ago, walking past some court buildings with a friend, I kept stopping to pick up paper clips. Besides the usual little Gem clips, like ACCO Brand Trombones No 1, I found a black-and-silver binder clip and a rare angel-shaped “ideal clamp”–all of them no doubt carelessly dropped by lawyers who once used them to hold together reams of paper and their clients’ worst fears. My friend asked what I’d do with these paper clips, what I do with all the paper clips I’ve picked up. “Do you have a big box, or some sort of display?” he said, clearly amused at the thought that I privately worshipped at a bizarre altar festooned with paper clips, like an ancestor shrine. I was offended. “No!” I said. “I use them!”

Not long ago, walking past some court buildings with a friend, I kept stopping to pick up paper clips. Besides the usual little Gem clips, like ACCO Brand Trombones No 1, I found a black-and-silver binder clip and a rare angel-shaped “ideal clamp”–all of them no doubt carelessly dropped by lawyers who once used them to hold together reams of paper and their clients’ worst fears. My friend asked what I’d do with these paper clips, what I do with all the paper clips I’ve picked up. “Do you have a big box, or some sort of display?” he said, clearly amused at the thought that I privately worshipped at a bizarre altar festooned with paper clips, like an ancestor shrine. I was offended. “No!” I said. “I use them!”

The trouble is, once you start seeing paper clips, you can’t stop seeing them. My obsession with lost paper clips started years ago, when I resolved to start gathering coins. I’d read some article that argued that only a fool would walk past free money and that taking a second to collect a coin meant that, at that moment, you’d be making more than minimum wage. I started scanning the ground for nickels, dimes, or quarters, but hardly ever found any. Instead, I saw the metallic flash of paper clips.

Figuring that one paper clip was worth roughly one penny, I started picking them up. This hobby seemed harmless at first, but I should have known myself well enough to foresee my vulnerability. Paper clips in the abstract do not move me—I’ll never read design-oriented books like “The Perfection of the Paper Clip.” What makes me feel weak and tender and deeply sad is the sight of a forgotten paper clip alone in a sidewalk crack. Continue reading