These thoughts on sneezing first ran back in October 2015, and I loved the responses. Feel free to share more examples of achoo styles from friends and family! It’s always a good time for a robust sneeze.

——

When we were kids, my brother was the sneezer of all sneezers. There was never just one, or even two or three. It was always 17. No lie. Each sneeze began with this strange little sucking in of air, a pause, and then from his bent body and contorted face flew ah-YESH-ah!

Seventeen times. He was very consistent. (He says he’s now down to seven.)

By sneeze number two, tissues were required—and employed, if time permitted, in between explosions.

My husband, meanwhile, sneezes so loudly and with such force that I can’t help but shriek. I beg for a warning but never get one. Even the second and third ones rattle me. They cause our old Jindo dog to drop belly-flat to the floor in fear. John is a big guy, with big lungs, who doesn’t hold back. So he sneezes larger than most.

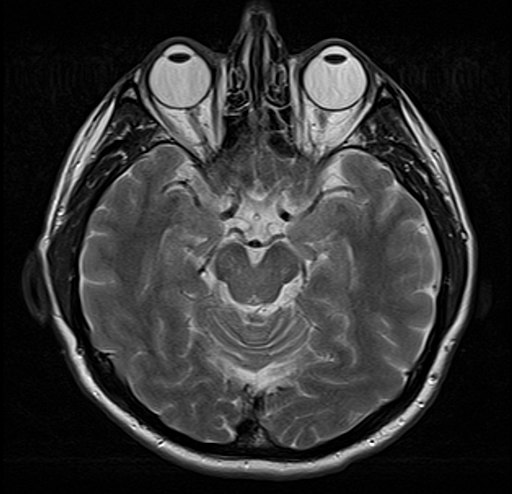

Sneezes are like fingerprints—we each have our own. But the physiology of a sneeze is the same for all of us. The trigger is usually dust or some other irritant trapped in the mucous lining of the upper respiratory tract. Cranial nerve endings fire off a message to the brain stem telling the lungs to take a deep breath. Your eyes and vocal cords close, then air explodes forth from the mouth and nose at upwards of 90 miles per hour.

There’s no way to look cool while sneezing.

Scientists call sneezing sternutation. Some of us sternutate (no, I’m not sure you can use it as a verb) when we look at the sun—called photic sneezing (I do that). A sneeze may build as we tweeze a hair from the eyebrow or nose (been there). Others achoo during an orgasm, apparently (so far, nope). Those responses—and others—are a bit of a mystery, but faulty wiring in the brain is likely to blame.

Do sneezes match personalities? A lot of loud (may I say obnoxious?) people are, after all, giant sneezers, and we all have that friend who really holds back, letting squeak out just a tiny, high-pitched choo at the very end. My mother did that, at least for sneeze number one. Any follow-up sneezes had force, and the same phonetic as (though less drama than) my brother’s: ah-YESH-ah. They were much like her, a seemingly polite and gentle woman who might without warning start a whipped-cream fight at the dinner table or make a joke about “taking the bull by the balls.” In a church.

From a very unscientific poll (thanks, Facebook) I learned that allergy sneezes tend to be harder to control than other types, many people sneeze in twos, and sneezing politely into the arm is far from universal. (Australians and Indians, according to friends, aren’t germ-phobic like we Americans; they share sneeze product widely. Sometimes right in your face.) A pregnant friend has decided that letting it all out is better for the fetus than holding back. Who knows if that’s true.

My friends seem to like sneezing. Here’s how some of them do it:

Often its loud-knock-the-china-off-the-wall sneezes…and out of the blue. Scares the bejeezus out of the mister.

Mouth sneeze, not through the nose. One sneeze, rarely multiples. All out. [A useful tidbit: Ear doctor taught me to suppress post-surgical sneezing (so as to avoid jostling delicate ossicular chain reconstruction) by snorting forcefully out through my nose, alternating with panting hard out through my mouth. Works pretty well.]

Face in elbow and let ‘er fly. Sleeve stops the splash damage and muffles the sound.

Definitely through the mouth. No hand gyrations or exciting body movements. Volume is excessive.

Once sneezed very delicately and got such an amazed and positive response that I now actually out of habit sneeze that way. It is about the only time I ever get called, “cute”.

My sneeze? Like my mom, I might go minimal at first but then I transition to a fuller more satisfying outburst. Why hold back? There’s obviously something in there that wants out. If needed, though, I can sneeze almost imperceptibly, with no product whatsoever. I’m pretty proud of that.

Meanwhile, the appropriate response to a sneeze depends on where in the world that sneeze happens. According to a fine list on Wikipedia, in most countries, a witness offers up God’s blessings or wishes you good health or long life. (We were a “bless you” family, although the German “gesundheit” was also acceptable.) Mongolians ask God to forgive the sneezer, and the Igbo apologize to or for the person. In China and Japan, it is customary just to ignore the whole thing.

But my favorite reply wonderfully states the obvious. If you speak the Australian language Ritharrngu, you might say after someone’s wet blast, “klas bin gurruwan.” It means: “You have released nose water.”

They don’t say “You have released nose water in my face.”

I guess that would be rude.

*

Possible future polls: Tissue or Kleenex? Whose dad still carries a handkerchief—and has he ever found a pocket booger? Does your sneeze match your love life? Stay tuned.

—-

Photo: Shutterstock