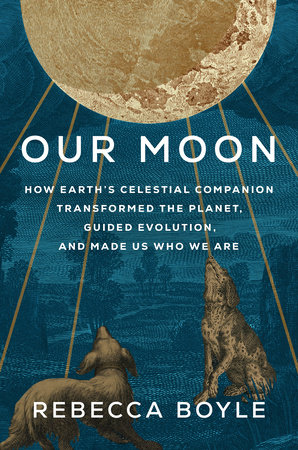

Our Becky wrote a book. It came out yesterday. It’s beautiful. And I got to talk with her about it.

*

Cameron: Could you tell the story about how this book came to be?

Becky: When I started working on this proposal, I imagined it as a sort of appreciation—here’s how cool the Moon is, here’s why you should care about it even though many astronomers find it dull, here’s what it has done for us. I wanted people to think about it in a way that transcends the modern rocket-measuring-contest obsession with going back there and mining or something. My editor, who is amazing, saw early on that this book was more like a history of human thought.

So when I started writing it, I wanted to connect its existence to our own, and our process of thought through time. And I set out to find some interesting lunar connections. As I found these different connections—ranging from the earliest methods of timekeeping, to the roots of religion and philosophy—I grew convinced that this wasn’t going to be an appreciation, but instead an argument. Like: The Moon is responsible for every giant leap we have made as a species. We would not be here without it, and here are all of the reasons why.

Cameron: Before reading this book, I’d never thought of the Moon from the Moon’s perspective. That is, I’d only thought about it as it looks from Earth. You write so beautifully about the Moon and some of the things it experiences–its own seasons and solstices, even a water cycle–and what it might be like to be on the Moon. What was it like for you to think and write about the Moon this way?

Becky: I really wanted the Moon to be the main character of this book. At one point I mapped out the chapters according to Campbell’s traditional hero’s journey — like, the Moon is the central character experiencing a journey of supernatural wonder, encountering forces acting against its interest, triumphing over those forces, and reckoning with the transformation that ensues. I think the ultimate structure is not quite that, but there are some echoes of it in the narrative. In the middle, for instance, the Moon falls from grace; once it is divorced from our notion of time, and Galileo and his contemporaries prove that it is just one satellite of many, the Moon faces its abyss. I tried to keep those narrative ideas in mind as I was writing. If the Moon was a character, what would it feel? Without ascribing too much agency or personification to the Moon, I really wanted to keep it and its experience front and center, whether that was to consider the physical traits that separate it from Earth, or to think about how the Moon experiences the sublime. I also really just love thinking about what it would be like there. I tried to focus on the Earthly things we often take for granted, and how much we would miss them when they were gone.

Continue reading