I’ve been talking to Richard Garwin recently and thought I’d run this again. The original had an update, not included here, that read: This post originally said the document on the computer screen is classified, and though it once was, it certainly no longer is. No one who knows Garwin would think he’d allow the filming of a computer screen showing classified documents. Just to say it again: that document on the screen is declassified. In case you’re interested, it’s http://www2.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/nukevault/ebb332/doc09a.pdf, formerly classified TOP SECRET.

Garwin is 4.5 years older now, which puts him over 90. I write “over 90” because math is not my best skill and because if Garwin reads this, I’ll get a brisk little email saying, “Thank you for writing this. I’m 91.15 years old.” Regardless, he’s still packing up and heading to DC because the government still needs to hear from him.

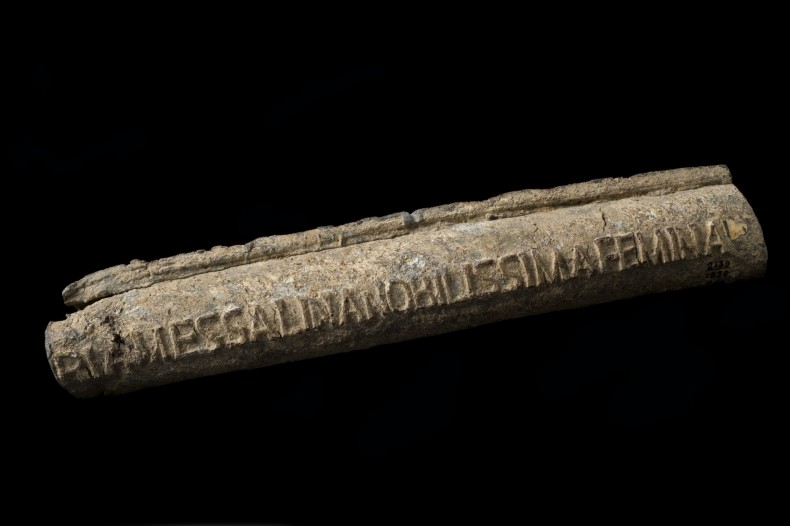

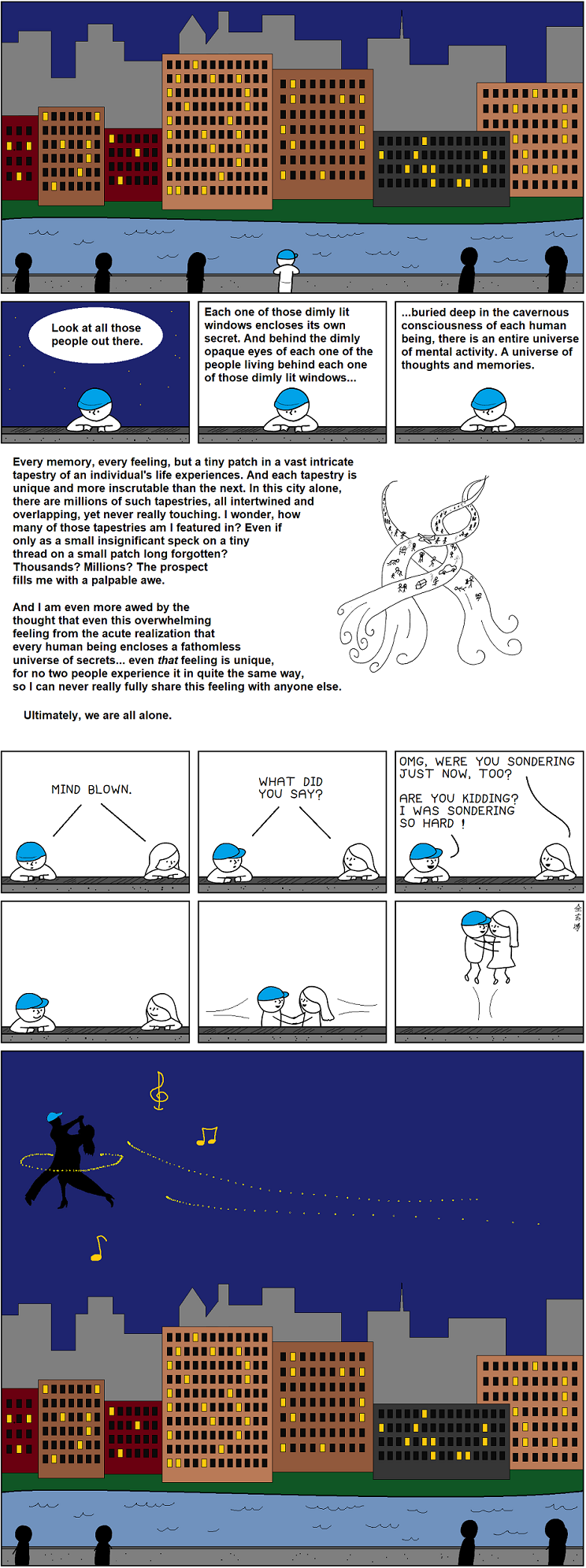

Garwin: the Movie opens with an old, steady, precise hand on a computer keyboard, scrolling through now-declassified* documents. Harry Truman and Dwight Eisenhower make announcements, and newspapers flash headlines about our splendid new hydrogen bomb. Then the blossom of a mushroom cloud unfolds; and John F. Kennedy talks about Russian missiles in Cuba; and the same old hand places a pill case near the keyboard, then dumps out his pills. Lyndon Johnson explains the complex problems of Vietnam and soldiers shoot their way through a jungle, and the old hand is tieing up a necktie. Walter Cronkite reports Three-Mile Island, and the old hand pulls on a suit jacket and slings a heavy backpack over his shoulder. The oil wells of Kuwait explode into a fiery smoking darkness, which becomes the smoking darkness of the Twin Towers, which slides into the tsunami slipping in slow motion over the drowning towns of Japan; and the old hand picks up an umbrella, and a heavily-burdened, slightly baggy old guy in a nice suit and tie stumps out onto the sidewalk, gets in a cab, and goes to DC. The film title slowly spells out the name, Garwin. The old guy gets out of the cab, slowly, creakily — he’s 86, after all — and walks past a group of anti-nuke demonstrators, stops and looks at them for a second, then walks on. He’s seen them before. He walks into the Executive Office Building. You know, he says, the president and his national security advisor, aside from their positions, “are really just ordinary people. And they need to make decisions and they don’t have time to learn. So the only thing that really works is education.”

Garwin: the Movie opens with an old, steady, precise hand on a computer keyboard, scrolling through now-declassified* documents. Harry Truman and Dwight Eisenhower make announcements, and newspapers flash headlines about our splendid new hydrogen bomb. Then the blossom of a mushroom cloud unfolds; and John F. Kennedy talks about Russian missiles in Cuba; and the same old hand places a pill case near the keyboard, then dumps out his pills. Lyndon Johnson explains the complex problems of Vietnam and soldiers shoot their way through a jungle, and the old hand is tieing up a necktie. Walter Cronkite reports Three-Mile Island, and the old hand pulls on a suit jacket and slings a heavy backpack over his shoulder. The oil wells of Kuwait explode into a fiery smoking darkness, which becomes the smoking darkness of the Twin Towers, which slides into the tsunami slipping in slow motion over the drowning towns of Japan; and the old hand picks up an umbrella, and a heavily-burdened, slightly baggy old guy in a nice suit and tie stumps out onto the sidewalk, gets in a cab, and goes to DC. The film title slowly spells out the name, Garwin. The old guy gets out of the cab, slowly, creakily — he’s 86, after all — and walks past a group of anti-nuke demonstrators, stops and looks at them for a second, then walks on. He’s seen them before. He walks into the Executive Office Building. You know, he says, the president and his national security advisor, aside from their positions, “are really just ordinary people. And they need to make decisions and they don’t have time to learn. So the only thing that really works is education.”

§

Richard L. Garwin, a physicist and inventor, has been educating politicians on the scientific realities, whether they want him to or not, in every administration since Eisenhower’s. He educates them on the physics of nuclear weapons, missile defense, jungle warfare, burning oil wells, terrorist attacks, and of nuclear plant meltdowns. The people who made the movie about him, Richard Breyer and Anand Kamalakar, originally pitched a film on the history of science in America, using Garwin like Zelig or Forrest Gump, they said, because at important moments in history, he always showed up. “But when we got to know him and hung out with him,” Kamalakar said, “it evolved into this other film about a person who built this horrible thing and worked his whole life to dance around it.”

The horrible thing is the hydrogen bomb. Back in 1950, Edward Teller was having trouble getting the design right, asked Garwin to help, and in a month or so Garwin had the plans for the bomb test called Ivy Mike. Garwin was 23. Afterward, he went back to Chicago, where he was a young professor, and walked around in his bedroom, wondering what he should do next, what he should do with his life. He apparently figured it out: he took a job at IBM, where he spent the next 41 years, on the condition that he be granted regular, frequent leave to give scientific advice to the government. After all, Eisenhower had said that the only way to win World War III was to prevent it, with the help of some good scientific minds.

The horrible thing is the hydrogen bomb. Back in 1950, Edward Teller was having trouble getting the design right, asked Garwin to help, and in a month or so Garwin had the plans for the bomb test called Ivy Mike. Garwin was 23. Afterward, he went back to Chicago, where he was a young professor, and walked around in his bedroom, wondering what he should do next, what he should do with his life. He apparently figured it out: he took a job at IBM, where he spent the next 41 years, on the condition that he be granted regular, frequent leave to give scientific advice to the government. After all, Eisenhower had said that the only way to win World War III was to prevent it, with the help of some good scientific minds.

§

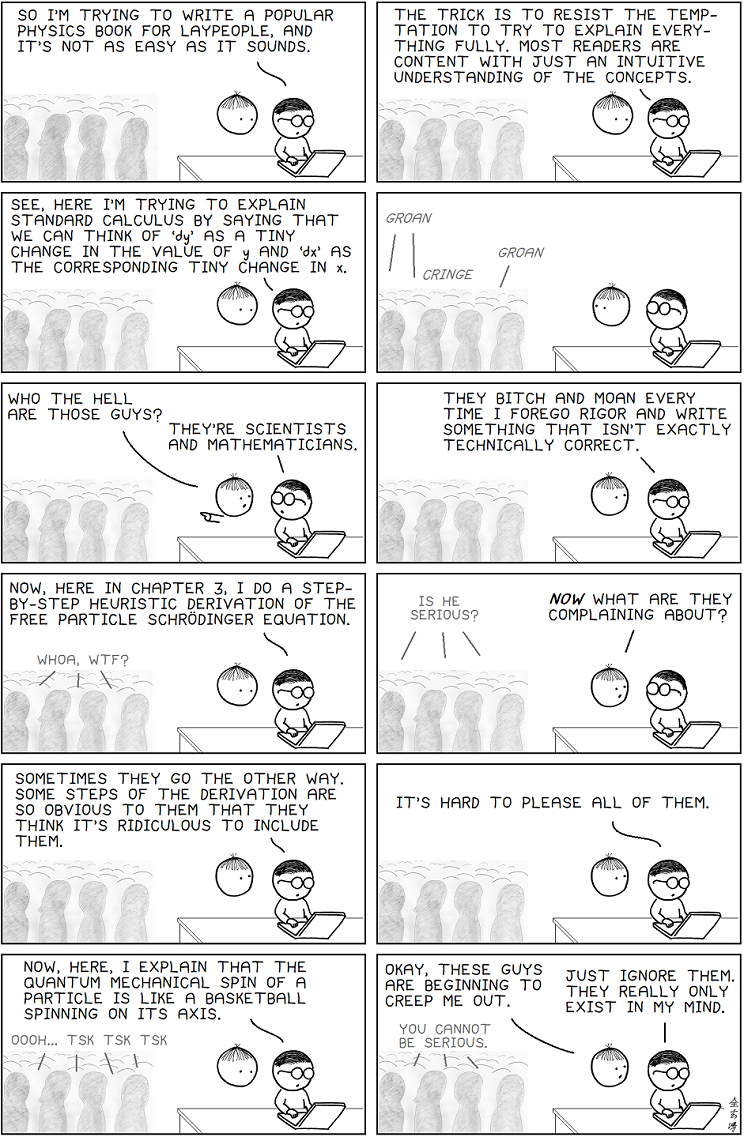

Sputnik goes up and the country panics: the missile big enough to carry Sputnik could just as easily carry nuclear warheads. The Soviet leader Nikita Khruschev pontificates, Americans build fallout shelters equipped with food and radiation monitors. Garwin says that the Soviet Union could destroy the US several times over, the only defense would be deterrence. Tests of nuclear weapons roar through the atmosphere. “Every time you pushed the button to detonate for a megaton fission yield,” Garwin says, “a thousand people are going to die [with cancer] as a result.” His old colleague Edward Teller convinces Ronald Reagan to fund Star Wars; artists’ conceptions show little missiles zamming into bigger missiles and blowing them all up in orange comic book flashes. The Star Wars systems never worked, missile defense still doesn’t work. “I’m not in favor of deploying systems that don’t work,” says Garwin, “and predictably won’t work.” The Russians build counter-measures to our defense systems that don’t work. “Nuclear weapons are much more a problem for our security,” says Garwin, “than they are good for our security.” The head of the Federation of American Scientists, whose mission is preventing nuclear dangers, can’t remember how long Garwin has been a member and notes that Garwin’s at the Pugwash conferences and on the Union of Concerned Scientists, with similar missions. “He gets around,” says the head, “one wonders, how many Dick Garwins are there?”

§

“In a documentary,” says Richard Breyer, “information comes second, the story comes first. We had to put a narrative to Garwin, we had to find a log line, the A story.” Going into the project, which was suggested and partly funded by an old Garwin family friend named Walter Montgomery, Breyer and Kamalakar had reservations about who Garwin was — a cold war guy, they thought, an inside man. But during the year and a half of filming, they got to know him; the word they like to use is “nuanced.” “History can have so many different layers.” Breyer says. “We’re presenting an historical character and the audience makes the judgment.” So their film, he says, asks questions that it doesn’t answer. The questions are about where culpability and responsibility begin and where they end, and the film remains ambiguous. “Garwin was 23 when he designed the bomb,” said Kamalakar, “and there was a war going on and are you responsible for the part you play or not? He did many good things, how do you balance it all?” The people who see the film also see the nuances and have to decide their own answers for themselves, and maybe any discussion then will also have nuances. In these days of us vs. them, religion vs. science, evil vs. good, people make fast and stupid judgments, don’t listen, and don’t change their minds. “In the end,” says Breyer, “ambiguity can take us to the next step of discourse, not things in black and white.”

§

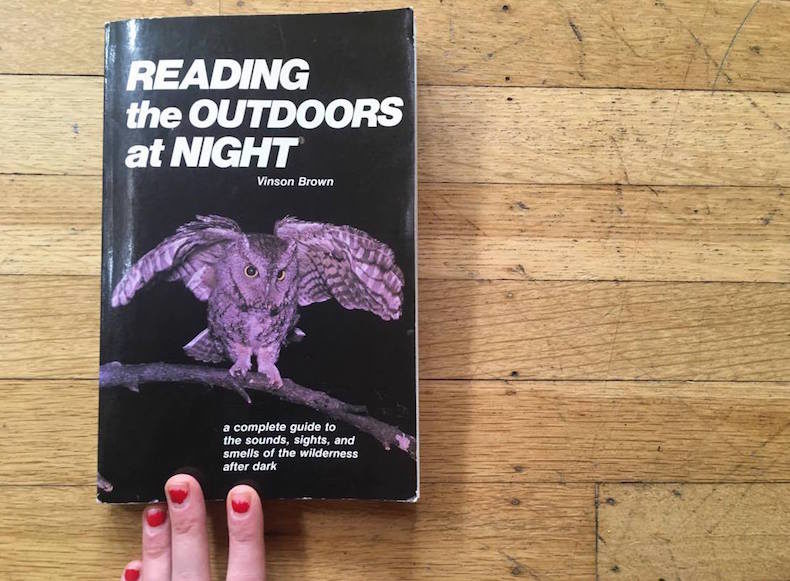

Garwin sits in an airport chair, working on a laptop. He gets up and puts on his backpack which holds his laptop and 15 or 20 pounds of reading matter, unfinished work, and documentation for argument. He walks to the gate, hands in his boarding pass. Then seen from behind, over the airplane seat, is the back of an old guy’s head, a few white hairs sticking up. “I haven’t spent a lot of time thinking about my role in bringing hydrogen bombs to the world,” he says. “But when I do, I think somebody else would have done it, probably a year later. It wouldn’t have made any difference. Am I proud of it? Yes, but not because of the destruction but because it was honest, it was in the interests of the country as the leadership saw it at the time.”

He gets off the airplane in Erice, Sicily, the annual meeting place of scientists who, among other things, give a prize called Science for Peace. He walks with another old, lively scientist, an Italian, through the ancient streets in the heat to a villa. Garwin stops for a minute, rearranges the papers in his backpack and zips it up, then the two of them start up some steep stairs. “Can’t you get rid of these big pack?” says the Italian. “Such a big thing. Always carrying papers and papers and papers.” They trudge up the steps. Garwin doesn’t answer and he’s still carrying the big thing.

___________

The movie’s website allows streaming. You can also call your local film society/science organizations/movie theaters to request screenings, politely but insistently.

Disclosure: I’m interviewed in the movie — God I look old — and provide some of the voiceovers. This is partly because I’d written a profile of Garwin. I enjoyed and admired the movie nevertheless.

Stills from Garwin: the Movie with the kind permission of Richard Breyer and Anand Kamalakar.