Back before I was an official LWONer, I was a Guest LWONer, and this is one of the pieces I wrote in that capacity. Because yoga is indeed a forever practice, it seems just as relevant now as back in 2014. Although, full disclosure, I do more Zumba these days than yoga–because getting older means one needs to jump around more to stay awake. But anyway, yoga is still my go-to when I need to wring out some rag water. Namaste.

Back before I was an official LWONer, I was a Guest LWONer, and this is one of the pieces I wrote in that capacity. Because yoga is indeed a forever practice, it seems just as relevant now as back in 2014. Although, full disclosure, I do more Zumba these days than yoga–because getting older means one needs to jump around more to stay awake. But anyway, yoga is still my go-to when I need to wring out some rag water. Namaste.

Yesterday the People of LWON discussed our hopes for 2020. Today, we reflect on what we hope to leave behind.

Ann: Serious answer is, that’s a little complicated. After a certain point in life, you’ve got more behind you than in front and surely it would be blind-stupid graceless to not weigh carefully what you want left behind. Given that, some things I’m just glad are over with — cataract surgery, a medically-uninteresting fainting spell, the argument with my neighbor over parking, the old friend I gave up on being friends with, the office next to the guy without an indoor voice. All small stuff. Anything big to leave behind? Not that I can think of. Isn’t that nice?

Jenny: I’m with Ann…as time passes the “leave behind” and “look ahead” questions loom large. But it’s not hard to find things to brush away: For me, a painful choice for my dear old dad, a long stretch of angry gut, a favorite aunt’s memory reaching its end. Also, a really ugly screen door (replaced by a beautiful mahogany one–I can share a photo if anyone cares) and self doubt about just about everything. Not that that last one will ever be gone gone, but I hope to continue to chip away at it. Perhaps that’s one good thing about getting older: We learn to care less about what we can’t control.

Emily: Most of the things I’d like to leave behind from 2019 are not going anywhere in 2020, or if there’s a chance they might go, I don’t want to jinx it. Like Ann and Jenny, there are a lot of things I’m hoping will stick around a little longer, like my 1999 Honda Civic hatchback, which just cruised past 200,000 miles. We had a washing machine that wouldn’t spin properly, leaving all our clothes sopping wet — so I’m glad that’s gone. But aside from the political dumpster fires we’re all sick of, there aren’t many things from 2019 I’m desperate to say goodbye to. I must have had a pretty good year.

Ben: I’m looking forward to leaving behind the disorientation that comes with living in a new place — in our case, Spokane, where we moved in July 2018. Yes, the process of discovery is exciting, but it’s also discombobulating to go through life without a go-to bar, hiking trail, or fishing hole, and it’s frustrating to know little of the environmental history of the place you live. Now that we’ve had a year and a half to explore, study up, and get settled, I feel less like an interloper in someone else’s town, and more like a local in mine.

Cassandra: All of the physical discomforts of pregnancy: Skin stretched so tight it burns and itches. The near-constant ache that comes with the brutal and unwelcome expansion of my ribcage. Back pain. A huge appetite accompanied by a stomach no bigger than a teacup. Forced abstinence. I could go on (and on and on and on), but I’ll leave it there.

***

Image courtesy of Sherman W. via Flickr

Happy American Thanksgiving! In the past we’ve written group posts about gratitude. This year, we thought we’d do something different: lay bare our hopes for the future. Here is what the People of LWON are most looking forward to in 2020.

Craig: The numbers, 2020, are pleasing to the eye and roll off the tongue nicely. Twenty-nineteen feels like a debacle just trying to say it, like every other letter is trying to stop you. If that’s the case, I’m looking forward to clarity. I’m thinking of 2020 like a clear pool of water, which after the burning of 2019 should be a relief.

That said, I’ve got to appreciate 2019 for the snowpack it gave to the West, one of the most heartening winters I’ve seen in a while. I figure 2020 will be dry as dust, per usual, but I wouldn’t mind being wrong.

Ann: I’m going to pre-empt everyone else wanting to say this because I’m gonna say it first: bad things end, and so the current administration and the accompanying political and civil and ethical wars will also end, and please please please, let this end be in 2020.

Jenny: A new year is a fresh, clean thing, a time to discard the crusty bits that inevitably accumulate–like those black things in the corners of my dogs’ eyes. I hope to flick those away and get a better look ahead. Maybe there’s wisdom up there.

Plus, all the things one puts off with a “maybe next year,” I hope to revisit, and actually do, in 2020. A certain trip. Some important financial decisions. An herb garden.

Emily: It’s been three years since I moved back to California. Even though I grew up here, I’ve still had to find my people again, like you do after a move. This process usually takes me about three years, and I finally feel like I’ve found the pack of friends I want to run, feast, and howl with. I’m looking forward to spending a lot more time with them. My landlord also just gave us permission to get a cat: a major 2020 news item, as far as I’m concerned. I’m looking forward to playing with my 2019 birthday present, a shiny red boat! Also: ditto what Ann said.

Ben: I’ll join Emily in pet-related anticipation. 2019 was my first-ever full year sharing a house with a warm-blooded non-human: That would be Kit, the 30-pound mutt we rescued from a shelter in Spokane. The first six months of dog companionship were bliss. I was awed by the unconditional love, the therapeutic benefits of petting, the trippy mind-meld of teaching another life-form the rudiments of your own language (even if “stay” remains something of an alien concept). Eventually, inevitably, I started to see Kit’s warts. Her ferocious desire to be cuddled can be crazy-making when it compels her into bed with us at 3 in the morning, and her street-dog past left her with some problematic aggression around other critters (just ask fellow LWONer Sarah Gilman’s own beloved, Taiga, who may still be traumatized from their single meeting). Now that the honeymoon is over, though, I’m able to love Kit more realistically and, in a way, more fully: As one wonderful bumper-sticker reads, “Proud Parent of Two Great Kids Who Are Sometimes Assholes and That’s Okay.” In 2020 I’m looking forward to the continued deepening of my interspecies relationship, my own improvement as a novice dog owner, and the establishment of boundaries — and maybe, Cesar Millan willing, another Kit-Taiga summit.

Cassandra: I am 33 weeks pregnant, so I should be full of hopes and dreams for the future. But mostly what I want is a reprieve from the special brand of all-consuming dread that has come to define 2019. The apocalypse may be nigh, but I don’t want to feel the black weight of this knowledge on my chest when I wake up each and every morning. I need a break.

Because Sarah wrote about grief on Monday and because today my son would have been 51, so then what else would I bother writing about except grief or rather grief as love’s subset or corollary or unavoidable consequence. Love → grief, love ꝏ grief. That little ꝏ sign, that side-ways 8, that’s the math/astro symbol for infinity. It looks like an infinite loop, like it comes & goes, one implying the other one, practically the same thing. This first ran June 13, 2011.

Last week Jessa wrote about psychiatric diagnoses moving from the quantum to the continuum, that is, from neat little packages to shaded subtleties and something called “a quantifiable baseline of life functioning.” The same week, Ginny published a story about the same diagnostic changes but specifically those for pathological grief – the problem being that normal grief already looks crazy.

I remember being at a meeting of a support group for bereaved parents maybe a year after my son died and listening to a sweet pretty lady tell how her golfing partner had asked her when she was going to get over her child’s death, and how the sweet lady had gunned the golf cart and run the partner over. The group thought her golf-cart reaction was reasonable and appropriate. I thought, with the amount of anger floating around in this group, we should form a roving SWAT team.

Anger, plus depression, numbness, apathy, isolation, bitterness, yearning, confusion, loss of meaning, you name it, newly bereaved people are a mess. So what grief is normal? What’s pathological? In the olden days of Freud, “pathological” was someone unable to detach themselves from the dead person and reinvest emotional energy in a living one, or maybe in a cat. The detach-and-reinvest model isn’t talked about any more but I suspect it still underlies the idea of pathological grief. Prigerson et al. — the world-class, experienced psychologists and psychiatrists who wrote the article Ginny cited — used not “pathological” but “prolonged” grief, and said that the field has had no explicit and standardized criteria for it

Prigerson et al. made an intelligent, thorough, and valiant attempt to create some criteria, and even though they’re trying to do science with the uncontrollable variables of the human mind, I don’t doubt them. Some bereaved people seem just too angry, depressed, bitter, yearning, isolated, etc. for too long; they’re in too much pain, they’re functioning too badly. When I met such people in the bereavement support group or while interviewing for a book I wrote, I felt they were unreachable, I couldn’t see where they were, they were in a dark little enclosed place — in a coffin, I thought, in their children’s company in death.

I did have a brief doubt about how long a person has to look crazy before being diagnosed as “prolonged.” The first years after my son died, I looked like a cubist-period Picasso and life looked like death, a flat back lake melting into a flat black infinite sky. By about year 4, I had cleaned up the house, was returning phone calls, meeting deadlines, and generally taking an interest again. That seems the usual time frame: after about 4 years, you’re indistinguishable from normal. Prigerson et al. interviewed people up to 2 years, well inside the 4-year window. But they weren’t finding 100 percent of their interviewees bug-nuts diagnosable, so I assume they took the worst cases and declared them “prolonged.” So, ok. After all, they’re looking for the “quantifiable baseline of life functioning” that Jessa mentioned, for a gray scale of dysfunction. So to put it all together, psych research says that after a couple years, some people just haven’t detached and reinvested enough that they can function normally; and now not-normal is quantified.

Here’s my only caveat: refine that word, “detach.” One day after I’d begun working on my book, I stepped wrong off a curb and fell, cut my knee badly, and went to my family doctor. He began stitching up the cut, and because he’s a gregarious fellow and knows I’m a writer, he asked me what I was working on. I told him. “That’s a subject no one wants to talk about,” he said. “People suppress that.”

I thought he meant people who had not lost children don’t want to talk about children’s deaths, agreed with him, and let the subject drop. He made a stitch.

“I lost a child, you know,” he said.

“I didn’t know that,” I said. “I’m so sorry.”

“Well, it was a long time ago. It was just a few months old, bad congenital heart problems,” he said in the off-handed, seen-it-all way that old doctors have. “I never think about it.”

“How long ago?” I asked.

“Thirty years,” he said. “It doesn’t affect me. The reason I think it doesn’t is, you don’t have a chance to get close in just a few months.”

I don’t remember him referring to this baby as “he” or “she,” only as “it,” an age, and a fatal condition. I thought, Ok, maybe he didn’t get close and thirty years is a long time, and I dropped the subject again.

“Are you going to put me in your book?” he said.

“I’d love to,” I said. “I’ve had trouble finding fathers who will talk about it. The interview would take several hours.”

He said, “I’d have to be anonymous,” made a tricky knot, then reconsidered.

“No, I don’t want you to interview me,” he said. “I don’t want to talk about it. I don’t want to dredge it all up. It would hurt too much.”

I thought I’d let that pass but couldn’t. “If it didn’t bother you too much,” I said, “maybe it wouldn’t hurt to talk about it.”

He started laughing. “You really know how to hurt a guy, don’t you,” he said. “Now I have to go see a psychiatrist.”

So before I left, I made a bargain with him. I would ask him again in a month, and if he still said no, then no. A month later, he still said no. “It was so long ago,” he said. “Time is the great healer and I don’t want to open up those old wounds.”

“Thank you for considering it,” I said, and thought, thirty years and a baby he didn’t get close to, and wounds that can still be opened.

“Detach.” For a long time, I had regular dreams in which my son was pale and weak, so sick he was going to die; or he was shut up and dying in a room I couldn’t get into; or he was alive right then but he’d have to go back to being dead. These dreams were unspeakable. But now, 24 years later, I don’t have them any more. In my dreams now he’s alive and going about his business as usual. Sometimes I dream questions, can he go back to school? is he not dead? And even in the dream, I know the answers: of course he can, of course he isn’t. Here he is, he’s right here.

_____

Parts of this post have come from a Mar 4, 1997 op-ed I wrote for USA Today (behind a paywall), and from my book, linked to above.

Photo credits: top – Kevin Dooley; bottom – Eric Vondy

The other night we were supposed to see a meteor shower with fireballs. That’s what they predicted, fireballs. My gal and I went out on the deck in the late fall chill, dropped a single sleeping pad, covered ourselves in a blanket, and stared up at a midnight quarter moon.

The Taurid meteor shower and its fireballs would have been visible between Aldebaran and the Pleiades, and a little to the right, except for the moon in our faces. We couldn’t see a thing around it, holding up our hands, shielding our eyes.

We live near the Colorado-Utah line, which is some of the clearest and darkest there is. The nearest town is certified as a Dark Sky Community, granting international recognition, a big deal for a high desert burg of 526 people. We live over a hill out of town and down near the rim of a canyon that looks across a horizon of nobody. Stars are numerous and crisp. Looking up, she calls the Milky Way the Galactic Chiropractor.

We’ve been watching the night sky for most of human evolution, nothing but space overhead. It’s not a habit you shake. We see supernovas and comets, the sky busy with far more than its seasonal cadence. You’ll notice Mars the night it enters retrograde. One night it’s moving ahead through the stars, and the next it’s turned around and swimming the other way.

Continue reading

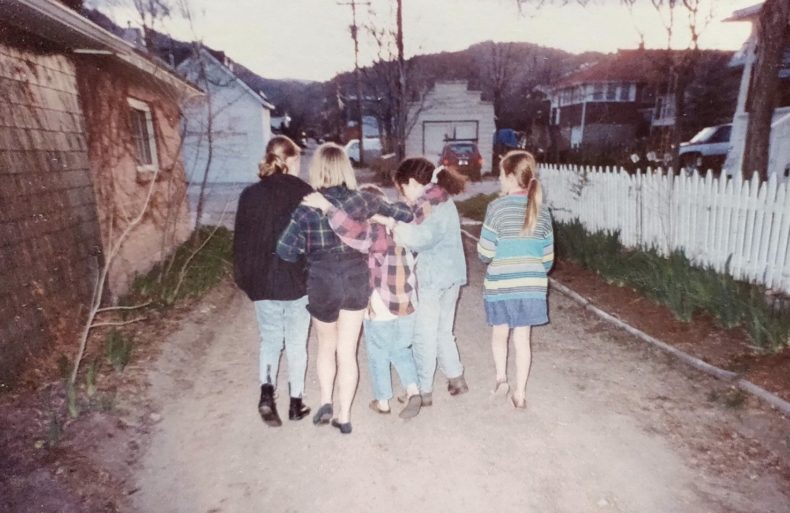

Do you remember when we used to yell at people from the roof? The light was longer then, and gold the way that it is in Colorado in fall, and we’d climb out your bedroom window and sit on the sloping awning over the porch and call out lines from movies to bewildered passersby. The lot of us were bony legs and arms lost in baggy clothes, then—members of a nameless generation that was not quite Gen-X and not quite Millennial. We were pre-internet and post-ennui, stringy haired and plaid shirted, sections of rope as belts, chipped nail polish and choker necklaces, pant cuffs frayed from slipping beneath our heels as we scuffed along sidewalks in combat boots or sneakers, our smiles marked with the metal trackways of braces.

None of us knew we were beautiful, then. We didn’t yet know how to love ourselves. But we were all in love with each other in that way that belongs only to teenage girls. Awestruck and skin-close, we drew on closet walls and each others’ arms, slept in down-lumped piles on the carpet when the VHS and whispering finally went quiet, slipped long notes into each others’ lockers, slipped into each others’ families. We were as tender as lovers, as vicious as sisters, knowing where the worst hurts lay, and prodding them when we needed to cover our own. We pushed aside our child selves, we tried to grow hard and sharp and cool and brilliant; we tried on things that the world insisted we should be, even as we fought to be something of our own.

Continue reading

The world of science entered November 6, 1919, as gray as a doughboy and exited it dancing like a flapper. That afternoon, British Astronomer Royal Sir Frank Dyson announced at a special meeting of the Royal Society in London that a recent experiment had validated a new theory of relativity. The occasion provided one of the few pure before-and-after moments in the history of physics—an occasion so rare that its very existence remains as impressive as both the theory and the brain behind it.

The centennial of the Royal Society announcement two weeks ago prompted the kind of tributes that Albert Einstein anniversaries usually do: essays and events chronicling the ascension of Einstein into the pantheon of the popular imagination. The topic is, in fact, endlessly fascinating, an enduring enigma: Why would a scientist become so famous for creating a seemingly indecipherable theory?

Part of the reason, as many commentators observed, was political. On November 6, 1919, the first anniversary of the Armistice of 1918 was only five days away, and an intellectual collaboration between a German resident and British scientists might well have symbolized the end of hostilities and hope for the future. Perhaps it even portended a return to fun and whimsy. As The New York Times headlined an article trying to explain the new theory to its readers: “JAZZ IN SCIENTIFIC WORLD.”

Continue reading

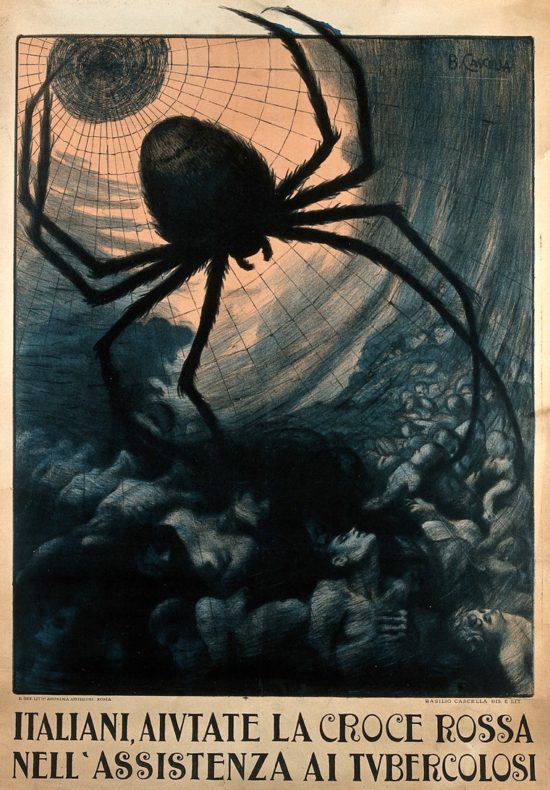

It’s spider season here on Knifecrime Island, but it looks like I’ve escaped this autumn’s offerings. At least that’s what I tell myself smugly as I prepare my first cup of coffee in the British predawn pitchdark of 6:39 am.

Anyone who’s ever watched a horror movie is already reading through thinly slatted fingers. Humming insouciantly – she doesn’t know! – I casually reach for a pan I left out last night – and instantly throw myself across the room. The thing that was waiting for me inside the pan is about the size of a human head, its arms and legs (and some more legs, and more after that) sprawling in every direction like a beer guy manspreading on a frat house couch. If that beer guy had hundreds of legs.

Scientists claim spiders have eight legs, but this is an obvious lie fed to us by academics who have never been alone in a dark room with a spider. From the furthest edge of the kitchen – a room in which I remain only to make sure that the thing doesn’t leg it into a new hiding place, all the better to surprise me with later – I inquire, in only a slightly elevated tone, whether my other half could please perhaps consider removing the interloper. A not reasonable request, you’ll agree.

Continue reading