I love museums, and my hometown, Washington, D.C., is full of them. You’ve heard of the big ones—the Air and Space Museum with the Wright Brothers’ plane, the Natural History Museum with its elephant and dinosaurs. We’ve got privately-owned tourist bait, like the Spy Museum and a branch of Madame Tussauds. Then there’s a pile of more obscure museums for everything from textiles to bonsai to individual government agencies.

I love museums, and my hometown, Washington, D.C., is full of them. You’ve heard of the big ones—the Air and Space Museum with the Wright Brothers’ plane, the Natural History Museum with its elephant and dinosaurs. We’ve got privately-owned tourist bait, like the Spy Museum and a branch of Madame Tussauds. Then there’s a pile of more obscure museums for everything from textiles to bonsai to individual government agencies.

One of those lesser-known government museums is the National Museum of the U.S. Navy. The museum is in the Washington Navy Yard, a former shipyard—and still a Navy installation— in Southeast D.C., on the Anacostia River.

The Anacostia, a tributary of the Potomac, is flat and tidal, which is why the Navy could build ships there. But that’s also part of the reason why it’s so darn polluted; its waters are slow and they rise and fall with the tide, rather than carrying all the crud out to sea. In recent years, the river has started to transform. There’s a new path along the right bank and way less trash than there used to be, although you still shouldn’t swim in it or eat the fish. On the walk to the museum with a friend, I saw gulls, cormorants, and two ospreys.

Our visit started in the Cold War gallery, after a check-in with a friendly guard. To me, the Cold War is about the Berlin Wall, world leaders banging their shoes, and children hiding under desks. But the Cold War had its hot aspects, too. The gallery is mostly about Vietnam, Korea, and nuclear submarines.

One cool piece was a map printed for airmen in Korea. It looked like a plain old map, but it turned out to be printed on silk—because silk is tougher than paper—and with water-soluble ink, so the markings could be easily removed. Another surprising item: a little bitty Steinway, the only piano ever to ride in a U.S. submarine. It was lowered into the U.S.S. Thomas A. Edison before the hull was welded shut.

Across a sunny parking lot is the main museum collection, in a long brick building that used to be part of the gun factory. It covers the Navy’s history since the American Revolution. There are lots of intricate models and bits of old ships. One corner is devoted to the “Forgotten Wars” of the 19th century. That includes the War of 1812 and the Barbary Wars, which were fought over state-sponsored piracy in North Africa; one of the battles is the origin of the line in the Marines’ Hymn about “the shores of Tripoli.”

Poking around the airy building, I was reminded how much science the U.S. Navy has been involved with. There’s a section on Antarctic exploration. I was charmed by the socks, mittens, and headband that explorer Finn Ronne’s wife knitted for him. He had navy funding to map the Antarctic coast. He brought his wife, Jackie, along and even named an ice shelf after her.

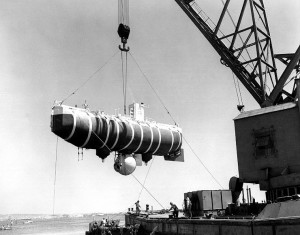

One of the museum’s treasures is all the way at the end of the building: the Trieste, an ungainly-looking vehicle for underwater exploration. It’s a bathyscaphe, which works kind of like a hot air balloon. Instead of rising and falling through air, it rises and falls through water using a huge gasoline-filled float and iron pellets for ballast. The occupants huddle below in a sphere with thick walls and a tiny window.

The Trieste was designed by Swiss scientist Auguste Piccard and launched in 1953, then later bought by the U.S. Navy. Its most remarkable expedition was in 1960, when Piccard’s son Jacques and Navy Lt. Don Walsh climbed into the pressure sphere and rode all the way down to the very deepest part of the ocean, the Challenger Deep, 35,800 feet below the water’s surface. No one had been back until this spring, when James Cameron went down in a one-man submersible.

It’s kind of odd to think that the same branch of the government that operated submarines with missiles aimed at foreign cities and printed silk maps with downed pilots in mind also explored the depths of the ocean and sent teams of people and dogs to map Antarctica.

Back outside, the same river that was sad and forgotten for decades now has kayakers enjoying the afternoon sun. We ran out of time and didn’t even make it to the museum ship tied up at the pier outside. I guess I’ll be going back for more exploration sometime.

Photos: Museum Exterior, Mayooranathan at ta.wikipedia [Public domain], from Wikimedia Commons; Trieste, U.S. Naval Historical Center

Another synergistic aspect of the Navy’s operations during the Cold War is the Arctic sea ice thickness measurements. These were taken by nuclear submarines in order to facilitate navigation over the Arctic, but now constitute a valuable source of historical information about Arctic sea ice conditions, important in assessing the role of global warming on the accelerated summer melting trend.