My phone buzzed just as I was finishing filming with the BBC Sky at Night crew for an episode about Mars, having spent the day immersed in the high-resolution panoramas returned by the Curiosity and Perserverance rovers. A text from a researcher wondered if I’d be around to comment on embargoed research from scientists in Cambridge who had ‘found new tentative evidence that a farway world orbiting a different star to the Sun may be home to life’.

I guessed immediately we were talking about the group who, back in 2023, had published what the peer-reviewed paper described as ‘potential signs’ of dimethyl sulfide (DMS), a chemical produced on Earth by plankton, and therefore a possible ‘biosignature’, betraying the presence of life on a small world called K2-18b in orbit around a red dwarf star 124 light-years away.

Such is the interest in (and perhaps desire for) alien life that even this very early hint of the possibility of a detection had garnered plenty of press coverage. Some posted the principal investigator, Prof. Nikku Madhusudhan’s caution that further data from the orbiting JWST would be needed to confirm the detection, but plenty did not. Now, it seemed, these new results were in.

My heart jumped. Aliens! Or at least the possibility of them. I got hold of the press release and the paper it was based on, newly accepted by the Astrophysical Journal Letters (Note that I am an editor for the AAS Journals, which includes ApJL; I had no involvement with, nor knowledge of, this paper during the editing process). Sitting on a rattling train heading back to Oxford, I dug deeply into both. More importantly, I started calling and texting friends and colleagues who work in the difficult business of measuring the properties of planets we cannot even see (K2-18b is only detected by the effect it has when it passes in front of its parent star).

Home, I settled on the sofa, reading the burgeoning literature on K2-18 and DMS which had been sparked by the Cambridge team’s previous results, pinging off requests for clarifications on statistics and astrobiological theory. What emerged over the course of the next few hours was a very different picture from that in the press release.

The detection was still tentative (in the paper it’s ‘3-sigma’, with a 99.4% chance of not being due to chance, but that estimate depends on exactly what one is comparing to what. Whole conference sessions could be devoted to the statistical intricacies.). The search for DMS had been motivated by the idea that the planet might be a nearby example of what Madhusudhan and co call ‘Hycean’ worlds, with a liquid water ocean deep under a thick hydrogen atmosphere, but other modellers think a magma ocean fits the data better. And the chemistry of such a world will be very different from that of the Earth, and so molecules which are biosignatures here – produced on Earth exclusively by life – may be no such thing on a different world, with different chemistry.. (See my Bluesky thread posted from bed early the next morning for details)

It was, frankly, a mess, but that’s to be expected. Barring the arrival of a suitably shiny spacecraft above a major world city, the search for life in the Universe even if it is ulitmately successful will be marked by the slow accumulation of evidence that is bound to often be confusing. That’s ok; in fact, it’s why this sort of science is fun. It was even acknowledged in the paper, which refers, for example, only to a ‘potential biosignature’ in the abstract, and which notes that ‘additional experimental and theoretical work’ is needed, in particular to consider how else DMS might be made.

Looking back at coverage that, in the UK, ranged from a front page in the Sun tabloid (‘The Planet of the, erm, Plankton’ was the headline) to a testy exhange on Radio 4, what strikes me is that gap between the paper and the press release issued by the University. Though it notes caution, suggesting further observations are needed to confirm what’s been seen, the press release does not have any trace of the broader caveats which are in the paper and which other experts raised. The paper reports ‘While [the presence of molecules] DMDS and DMS best explains the current observations, their combined significance…is at the lower end of robustness required for scientific evidence’ but the press release quotes Madhusudhan “The signal came through strong and clear.” Even with a very charitable reading, those are not the same thing.

(The press officer responsible was kind enough to confirm to me that quotes in the release come from interviews they conduct with the researchers, which are then checked by them before release.)

There is caution in the press release (‘It’s important that we’re deeply sceptical of our own results, because it’s only by testing and testing again that we will be able to reach the point where we’re confident in them’) but in it and in Madhusudhan’s interviews and briefings, the caution was attached only to the need for more observations to improve the statistical significance of the result. The myriad broader unknowns – whether DMS could be produced without life, and whether there was evidence for an ocean at all – which were raised by every expert I spoke to – were not mentioned at all. The line ‘Strongest hints yet of biological activity outside the Solar System’ which heads the release might even be true, but there’s still an enormous gap between where we are now and anything ‘strong and clear’.

‘Scientist wants publicity for work’ is hardly news, and nor is ‘researcher more convinced of their own results than their peers are’. This is the normal process of science, and it’s also not surprising that the story flew around the world. The Cambridge press office (who I’m pleased to acknowledge are acting as storytellers, without being instructed to aim for a specific number of hits), and many of the scientists and journalists who reported on the story, did a great job of conveying the nuance of where we are, and I don’t think science is well served by waiting until things are certain before talking about them publically.

We want to show how science, in all its messy, human glory, is done, and allow everyone to follow along as debates are resolved, but I can’t escape the feeling that something has gone wrong here in the translation from scientific paper to newsprint. I’d like to propose a golden rule for press releases:

A release should convey to its audience the same impression of a result that an independent expert would get from reading the paper which describes it itself.

This means obviously that one can’t exagerrate the significance of a result. But it also means that if one knows that the expert audience addressed by a paper will have broad questions, those need to be in the release too. I’m reminded of the late, great Tim Radford’s rule that science journalists should, ‘if an issue is tangled like a plate of spaghetti…regard [the] story as just one strand of spaghetti, carefully drawn from the whole. Ideally with the oil, garlic and tomato sauce adhering to it’. It should be the responsibilty of the press release to point to the existence of the whole plate of pasta, not only present a single delicious piece ready for consumption, even if that’s uncomfortable for the institution or scientist involved.

The idea that we’re close to finding molecules produced by alien plankton, lurking in an impossibly alien sea under the thick clouds of a world that’s closer to Neptune to Earth, enlivens any news bulletin. The search for life is the grand adventure of astrophysics in the next fifty years. But in the journey toward understanding how unusual we are in the Universe there will be many false steps and confusing results, and we need to be able to communicate this mess as we go.

__________

Chris Lintott is an astronomer at the University of Oxford, where he thinks about unusual objects and how to find them. He is also the 39th Professor of Astronomy at Gresham College, which has been providing free lectures to the City of London (and now online) since the 16th century. His favourite spaghetti dish is Pasta Puttanesca.

_________

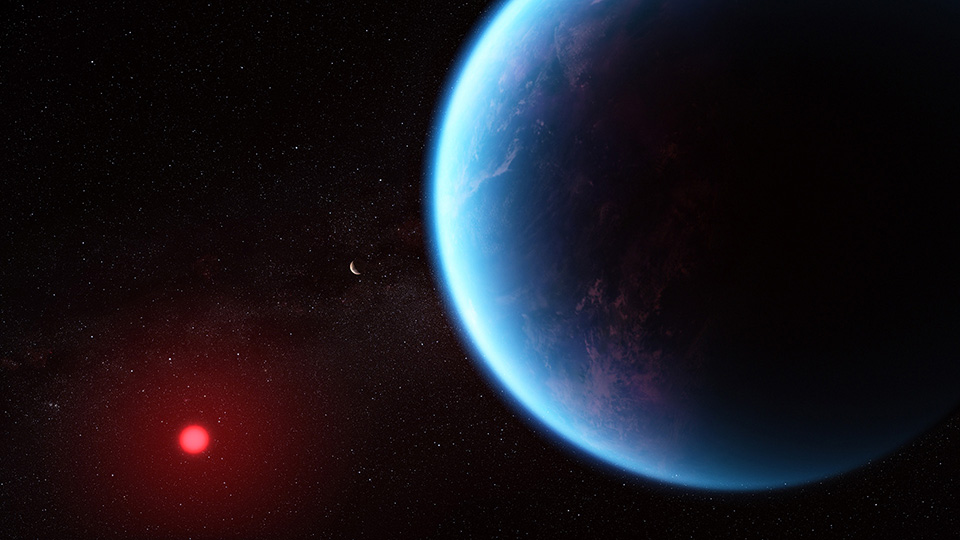

An artist’s impression based on the Cambridge group’s thoughts about what K2-18b might be like. Illustration: NASA, CSA, ESA, J. Olmsted (STScI), Science: N. Madhusudhan (Cambridge University)

Good sense Chris. I heard the “testy exchange” on R4 Today: “that’s the difference between a practitioner and a commentator” without any apparent self-awareness of natural bias in favour of his own interpretation.