This post first appeared in March 2023. I can’t wait to go to the beach again.

Walking south along the beach towards Los Angeles this weekend, my friend and I were talking about all the arbitrary things that can alter a life’s trajectory, like where you’re born or if your parents went to college.

As we walked, we noticed hundreds of tiny sea creatures scattered like dark blue flower petals along the water’s edge. Some were as small as a baby’s fingernail. Others were as big as silver dollars. When we looked at them up close, we saw that each animal had a flat, blue oval disc for a body, joined to a transparent sail.

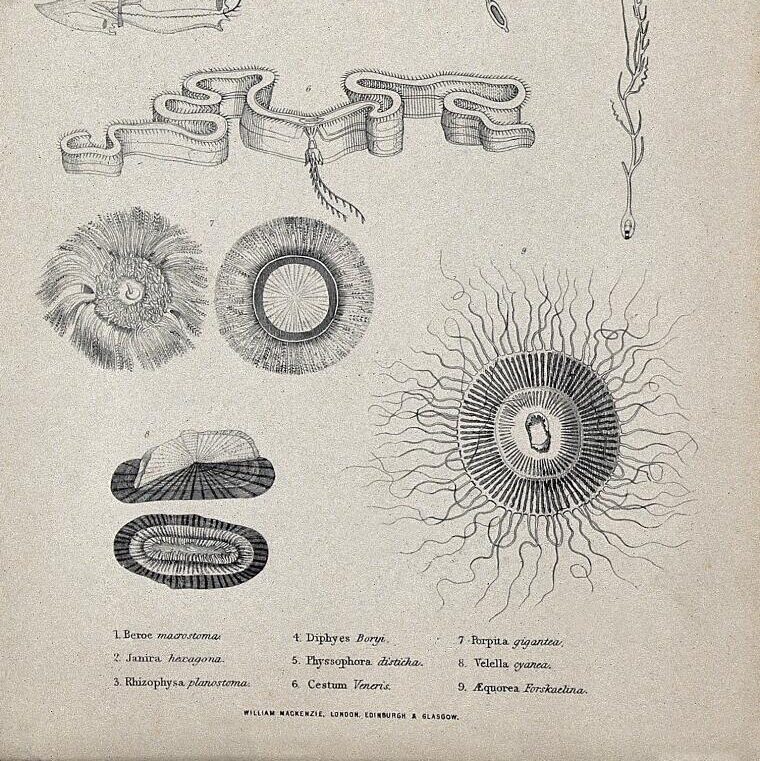

We prodded the stranded animals gently to see if they were alive or had any stinging venom, since they looked a lot like jellyfish. When nothing happened, we started arranging them in a line on the damp sand, from small to large. All the sails curved in a shallow S–shape, and were angled slightly to the left. They looked like a fleet of ships waiting for a general’s command to launch. Later, we learned that the strange blue discs were called Velella velella, or by-the-wind-sailors.

Although they look a lot like jellyfish, velella are more closely related to sea anemones. It’s as though, long ago, a sea anenome broke free from its secure attachment to a rock or the sea floor, and drifted to the ocean’s surface. Somewhere along the line the descendants of that anemone decided to make the blazing ocean surface their home.

Scientists are still debating what velella are, exactly — some think they are one animal, with a tentacled underside that serves as a single mouth. Other researchers think of them as a consortium: many individual tentacled polyps working together to find food and travel and reproduce. No matter how they work, velella are wildly successful – to the point that they can sometimes be a nuisance, carpeting the sea surface and washing up in massive heaps during storms.

The species has two mirrored forms – one with the sail angled to the left, and one with the sail angled to the right. The angle of the sail determines which direction the animals can travel in relation to the direction of the wind. Left-angled sailors are more common off the California coast, for example, likely because prevailing winds generally drive them away from our beaches. But over the past few months, fierce onshore winds have driven huge numbers of left-angled by-the-wind-sailors ashore.

My friend and I tried to imagine having a body built to go either left or right, towards destruction or survival. Floating in the open ocean with no arms to swim, no legs to kick, no paddle, no motor. Just the wind and the waves pushing you helplessly across the ocean. The velella’s indigo blue pigment provides camouflage and sun protection, but the color was starting to fade as they dried out in our arrangement. Meanwhile, we were getting sunburnt.

My friend waded out into the water, waving at me to follow. I dove under a wave. Once I wiped the saltwater out of my eyes I could see what she pointing at: a by-the-wind-sailor regatta bobbing on the surface. They were almost invisible against the blue of the ocean. But there they were, their tiny tentacles combing the water for plankton and fish eggs.

These velella were headed for shore, where they’d soon be stranded and die. Somewhere out in deeper water, they’d ejected countless medusae, the animal’s sexually reproductive form. The cartoonlike creatures were probably already thousands of meters deep, making embryos. When they were ready they’d half-swim, half-float to the surface and make their own life rafts out of raw ocean, with circular chambers of trapped gas bubbles. Then they’d build a wafer-thin sail out of chitin, catch the wind and fly across the sea surface at speeds of up to 20 knots.

Suddenly the velella didn’t seem quite so helpless – just lucky or unlucky. Sometimes the wind was in their favor, and sometimes not. A bit like us.

Aren’t they amazing?! My partner and I live on California’s north coast and see these Velella Velella fairly often. At times the entire beach is literally COVERED in blue… A fascinating world we live in, yes we do.