It’s Atacama Week at LWON. This post originally appeared March 19, 2018

Most of us probably remember the first word we spoke in our native language.

Mine was “Cat,” for I was fascinated by the ornery old Siamese that my parents kept when I was a baby. From there, I’m sure, I learned a child’s standard repertoire: “Mommy,” “Daddy,” “Doggie,” the colors red-yellow-green-blue, and those most basic early expressions of desire, “Love,” and “NO!”, and “I” and “Want.”

Most of us probably remember our first word in our native language, but I doubt many of us can remember a time when we knew so few words that we had to expand their definitions to cover an entire universe of necessary expression. When the word “Mom,” depending on how we said it, had to stand for everything from fear to hunger to whatever as-yet-inscrutable emotion was blowing through us.

I know I don’t remember. I work with words for a living. When I want to say, for example, that I’m cold, I have dizzying array of synonyms and phrases to call upon, each with different connotations and levels of extremity. I could be chilly or frigid, freezing or frosty, even glacial, hoary, icy, wintry, or just plain numb-lipped-club-footed-broken-fingered cold.

Then, I spent two weeks in Chile’s Atacama Desert this January. Only three of my five companions spoke English. When they talked among themselves, they spoke exclusively in Chilean Spanish, which, one of them—Fernando—gravely informed me, is even worse for outsiders than Argentine Spanish. I was awash in a sea of musical sounds whose meanings I could only grasp at based on context and hand gesture. Or from incessantly badgering the English speakers to help me out.

When Fernando grew tired of translating, he would turn to me and say drily, as if casting a spell, “By the end of this trip, you will be fluent in Spanish.”

Decidedly not, but I did learn the word for “key” – llave – since our two pickup trucks were our lifeline to food, water, and safety in the event of emergency. We were searching for burrows where desert creatures were living, so I also learned several words for those: hoyo, cavidad, agujero, hueco. And of course, being in Chile, one of the first words I learned was for barbecue – parilla – and more importantly, steak – palanca – which we ate almost raw, cooked over the coals of a campfire.

When the others addressed me in English, they were building a narrow bridge, trying to use the array of practical English words at their disposal to help me arrive at a much more complex and nuanced set of ideas on the other side. Sometimes, this happened entirely by accident.

When we found holes, we would smell them as a coarse way of discerning whether there was something hiding inside. If Fernando detected an odor, he would speak in English for my benefit and say, triumphantly, “I feel something!” If he detected none, he would say, dejectedly, “I feel nothing.”

His novel diction was better than standard, for it transformed the mundane action of sniffing a hole into something much more existential, with higher stakes. Which, when you’re driving around the driest nonpolar desert in the world looking for life, is pretty dead on.

After I returned to my home in the U.S., I decided to keep learning Spanish, and signed up for a beginners’ class. Each new word was like a bowl. Its uses had to be many, and its weight of meaning grew as I filled it with the associations that build from use.

As spring deepened, I would take runs each afternoon, and try to explain things to myself with the tools I had. Estoy con sueño means “I am sleepy,” but translates literally to “I am with dream.” “I want to see blooming magnolia trees” became Busco las flores de los árboles – I look for the flowers of the trees. And somehow this all felt more right.

Because sleep, for me, is transit into strange new worlds where elk are amphibious and sharks look like 30-foot-long flatworms. And because it was the flowers themselves that I sought, for the sole fact that they grew, wildly and hugely and improbably, not from stalks in the ground, but from trees. In having to rely on more general words, I had to find different paths to specificity. And somehow this got me nearer to the truth.

There is, in the transit back and forth between tongues, a serendipitous poetry. It makes me think that learning one is not so different from being reborn: New language upends the familiar into beauty.

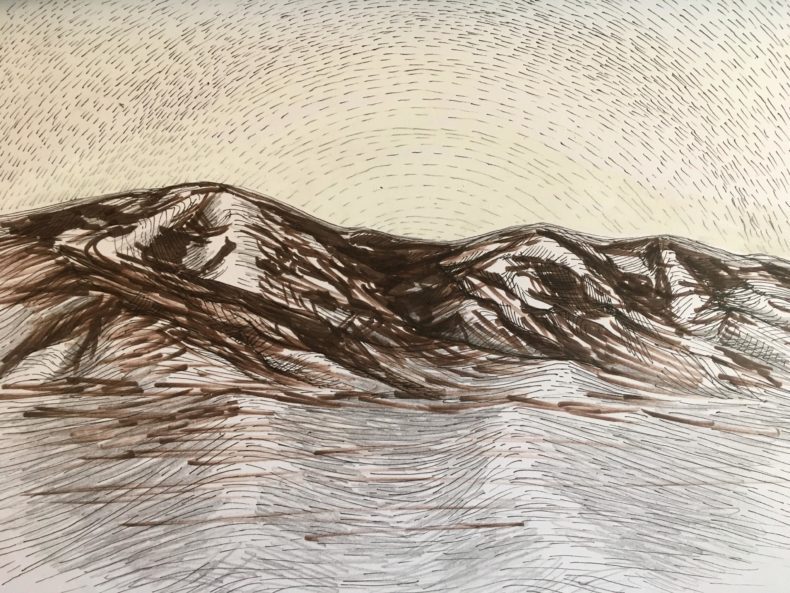

Original drawing of the Atacama by the author.