“Whether we like it or not, there are things out there, not alive, that think about us,” wrote a contributor on the internet anthropologist Katherine Dee’s substack. He was talking about the networks of technologies designed to stalk our movements and use the information to influence our decisions and command our attention.

In the age of these infinitely networked technological megafauna, how do you know if anything you are dealing with on the internet is under human control or driven by its own opaque desires? What is watching you? How will it act on the information it harvests?

I have begun to mentally categorise these nonhuman entities along the same lines theologians once taxonomised them in the old grimoires:

Fairy folk. What better description of deepfakes than “creatures with human appearance, the ability to disguise themselves, and a penchant for trickery“? Old legends offer signs to check that you’re in the presence of fae, and they are not unlike a meme I used to see on Twitter, counseling how to distinguish human photos from deepfakes: “Count their fingers and their teeth.”

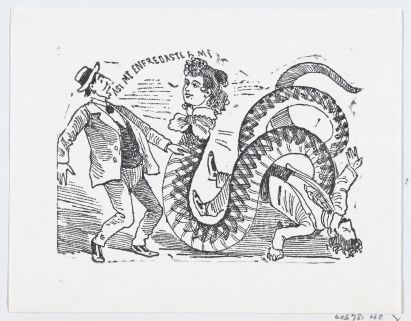

Lamia. Catfishing, pig-butchering, romance scams – all variants of a long game in which what appear to be lovely, doe-eyed ladies (or, less frequently, Brad Pitt) profess their devotion until your bank account has been drained, and then they slither on their snake-like tails back into the mists from which they emerged.

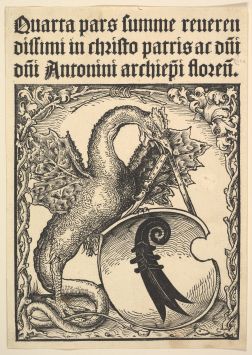

Basilisk. Ransomware can kill with a single stare. Don’t let it perceive you! Modern Basilisks have names like Rhysida and Lazarus Group, and they have taken down major critical infrastructure, from the UK’s NHS, to the British Library, to the US petroleum infrastructure.

Golem. How else would you think of an AI agent that you build to carry out your instructions? Instead of clay or mud, a modern would-be Golem-wrangler uses silicon and electricity to whip up a creature that serves their purposes. (These purposes, including making reservations at a restaurant and doing your Amazon shopping, may be less important than those which required building the original Golem.) Your AI agent obeys your will, but sometimes imperfectly, and with results that can be unpredictable.

Demons. They called Twitter the hell site, but which social network isn’t? The idea that each of the seven deadly sins is embodied by its own social network is a very old idea that’s been floating around since the days when we only had one social media site per sin. A modern update is available, thanks to Binsfeld’s classifications of the princes of hell (1589), which can now be used to categorise various social media subtypes according to who’s in charge: Lucifer, king of Pride, rules over Linkedin; Mammon, prince of Greed, looks after the crypto social apps; Asmodeus, prince of lust, is in charge at OnlyFans and Tinder and the like; Leviathan, prince of Envy, is boss at Instagram. Beelzebub is in charge wherever you gluttonously order your “burrito taxi,” but he sometimes job-shares with Belphegor, prince of Sloth, who is also in charge at Tiktok and YouTube. And finally (and not to put too fine a point on it) the guy calling the shots at Twitter is the prince of wrath himself, Satan. He recently renamed it X.

I’ve been trying to articulate this feeling for at least 7 years, this growing sense that the more technologically sophisticated we become as a species, the less “technological” (in the rational, Mr. Spock sense of the word) we become in our minds. Maybe this is happening because our old rational defenses are no longer adaptive in the nebulous realm we built with the internet. The Turing test no longer applies. Too bad we put all our 20th-century era critical infrastructure on here before we realised this place works by other rules.

Maybe this also explains the deep weidness of the conversation around artificial general intelligence and chatbots. “The leading A.I. companies are actively preparing for A.G.I.’s arrival, and are studying potentially scary properties of their models, such as whether they’re capable of scheming and deception, in anticipation of their becoming more capable and autonomous,” wrote Kevin Roose in the New York Times, not some millennarian nutjob talking about demons.

Read his sentence again. Our engineered infrastructure has turned into something we no longer entirely control but whose behaviour we must study and observe, like biological organisms. This was already obvious to the thinker George Dyson, who observed in his (extraordinary) book Analogia that:

“Nature’s answer to those who seek to control nature through programmable machines is to allow us to build systems whose nature is beyond programmable control.”

And I think this is why we are seeing a return to some older ways of coping with the world. These approaches were jettisoned in the 20th century with a rising confidence that humans were machine-like in their rationality. We could leave pre-modern, non-rational ways of thinking behind. But now it’s time to lash ourselves to our masts again, as Chris Hayes points out in his new book: not only will our technology fail to protect us from the sirens, our technology is the sirens. I think this explains the resurgence of interest in stoicism.

The open question I am struggling with is: does the 21st century still come after the 20th century?

Art Sources

I use Cosmos and the Metropolitan Museum of Art to find images in the public domain. They are all linked to their original source.

Main image: Detail of a miniature of a human-headed satanic dragon, representing the papacy of Urban VI whose election was contested and resulted in the appointment of the anti-pope Clement VII, from Joachim de Fiore’s Vaticinia de Pontificibus, Italy (Florence), 2nd quarter of the 15th century. Source: British Library.

Fairy. “Robert’s first interview with Mr. Stops”. From Punctuation Personified: or, Pointing Made Easy, John Harris. The Public Domain Review.

Lamia: A snake with a woman’s head slithering towards a scared man, an illustration from ‘The Ballad of the Snake Woman’ (reprinted 1930). José Guadalupe Posada Mexican. Source: The Met.

Basilisk. Basilisk Supporting the Arms of the city of Basel. Master DS Swiss. Source: The Met.

Golem. L’Homme Qui Marche. Eugène Druet. Source: The Met.

Demons. Joseph Anton Koch, detail from Casa Massimo frescoes in Ariosto Hall, Rome. Inferno, Canto XVII: Virgil and Dante riding the monster Geryon. Source: Public Domain Review.

Brilliant! This is just what I needed to read today. I’d been considering the names of saints and demons (and fantastical creatures of all kinds), your analogies to digital technologies is so on-point. Thank you so much!

Thanks so much for reading, Sandra – I’m glad it resonated