This summer, my parents pulled out an ancient family VHS tape and we all gathered around to watch a video of me at 18 months old, in a full body cast that extends from my chest to my right foot. My femur is broken, a spiral fracture, into seventeen fragments — the result of a freak sandbox accident.

These fragments will, I want to go back in time and tell my parents, fuse into a perfectly strong bone that can take me anywhere: I’ll run trails and climb the Tetons. But for now I am scooting around on a hideous brown and yellow carpet that they won’t rip out for at least another decade. I’m on my stomach, playing with an assortment of dolls that appear to have very complex inner lives and relationships. I am sternly admonishing one Barbie while ignoring the camera. I became more cautious after the broken leg, my mother says. “You knew you could get hurt.”

Watching this video has new meaning now that I have a 3-month-old baby. I feel more protective toward my own 18-month old body, which looks so much like Will’s. I can more fully imagine what my mom went through, turning me over in bed every couple of hours at night to prevent bedsores. I also understand better why this incident dominates my parents’ memories of my childhood. I don’t remember it, but it was a defining experience for them, the first threat to their first daughter.

Will, too, is in a period of forgetfulness. According to psychologists and neuroscientists, he won’t remember the emergency C-section, or his first shots, or our sleep-deprived blunders. There are various theories for what causes this infantile amnesia — some say it’s because babies don’t yet have a distinct sense of self; and/or they lack the words to form a narrative; and/or an infants’ hippocampus isn’t fully developed. But he’s still squirreling away other kinds of knowledge – our faces, our words, the way it feels to be held and to touch.

There are lots of other videos from my own childhood, of birthday parties and choir performances and community theater productions, me fully recovered and happily swimming toward my mother in a pool. But the painful memories have a sticky quality. I wonder constantly about the memories Will is forming — what preferences and aversions are already there or undecided, what colors and shapes will form the back, mid and foreground of his consciousness.

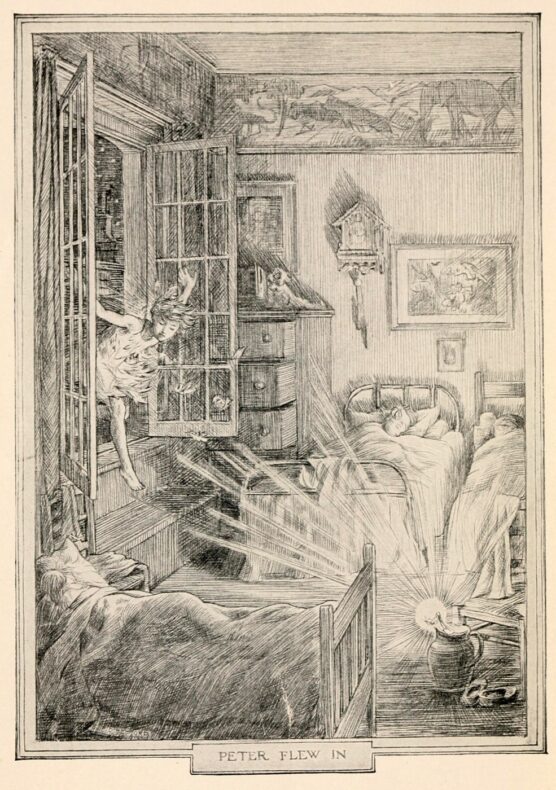

Nearly every night, when I put him to bed, I think about this passage from J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan:

“It is the nightly custom of every good mother after her children are asleep to rummage in their minds and put things straight for next morning, repacking into their proper places the many articles that have wandered during the day. If you could keep awake (but of course you can’t) you would see your own mother doing this and you would find it very interesting to watch. It’s quite like tidying up drawers.”

I don’t know about Barrie’s prescription for being a good mother, but I love the metaphor. Is there any parent who hasn’t wished they could get a glimpse of their child’s interior world? But as Barrie knew, we can only influence, not control, the memories our children retain and the stories they’ll tell about them. Will’s mind is like the blackberry thicket in our backyard, an unruly, fast-growing tangle of sharp thorns and sweet fruit.

People used to think memories were intangible – something impossible to grasp or capture. But now we know that they are material: made of connections between neurons, or synapses, that the brain constantly weaves and unravels. Some memories last for seconds or hours, while others persist for decades. But even our oldest memories aren’t static, and like bones, they can heal and grow like we do.

I’m still sifting through my own freshly formed memories of parenthood. It will take a while to forget that glimpse of my own viscera during the emergency C-section, organs spread apart and rearranged by a dozen gloved hands. Likewise, the vibration of Will’s first yell against those organs, which I could feel because the spinal anesthetic blocked pain, but not pressure and touch. But also: The first half smile he gave me. The first time our eyes locked in what I could have sworn was mutual recognition. Is this terror or clarity? Exhaustion or joy? It’s all of those things, I’ll tell Will someday, and more.