This week is the 79th anniversary of two nuclear weapons used on a human populace. In remembrance, I look to the region where the first bomb was set off as a test, less than a month before it was used against the Japanese people.

Where this devastation begins is hard country, Jornada del Muerto, which means journey of the dead. The name came before “Trinity Site,” and was taken for the bones of a horse and rider found there by a Spanish party more than 350 years ago, as if some poor fool and his horse had stumbled into the Book of Revelations.

I can only imagine the test site was chosen for its emptiness. Hardly a soul lives around here even today. Downwinders still pay, and for many, the government that did the deed won’t cover the cost. My family is from a town a hundred miles west, downwind in southern New Mexico. We don’t talk about it.

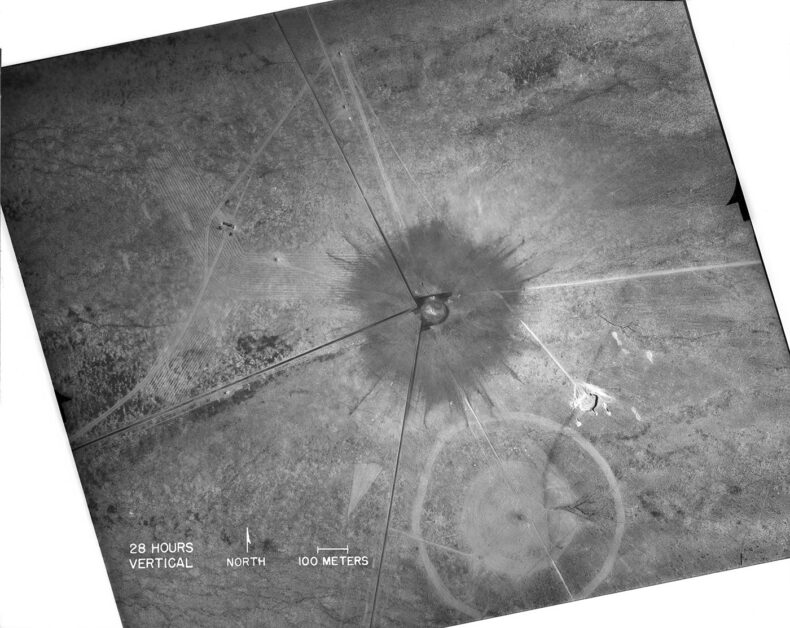

The basin is now marked with a hot crater half a mile across. An event of such magnitude in human history resonates in all directions through time. In the Pleistocene, the detonation site would have been under a lake, part of a chain of sparkling mirrors, some taking up the whole horizon. The next big basin south is now occupied by an active bombing range, a perfectly flat geography called Ancestral Lake Otero, a place that no longer has a lake. Its once muddy shorelines have produced a litany of Ice Age tracks, Columbian mammoth, big cat, giant ground sloth, human. Now it is barren, nearly lifeless. When the wind blows, the sky turns to zinc.

I walked there with a few friends years ago. The fence at the edge of the bombing range was down, or so drifted with white gypsum that it was buried. We had a camp nearby and one day strolled across a blank interior where we heard atmospheric concussions of missile tests far away. One of the friends had worked as a bomb diffuser for the Army in Iraq and he said we wouldn’t hear an incoming missile until the instant it struck, and if the direct impact didn’t kill us, the concussion wave collapsing our lungs would.

The first atomic bomb was detonated five miles from a gunsight gap between low, rough buttes. Here lies the one of the largest Paleolithic hunting encampments documented in North America, a center of Clovis activity strewn with single-use fire pits and the debitage of stone tool manufacture from about 13,000 years ago. This is the Mockingbird Gap Clovis site. Tool-stone found here includes rock carried south from what is now northern New Mexico by Paleolithic tool makers. Some of this raw material was imported from near Los Alamos, and here in these basins it was fashioned into the famed Clovis point, the height of weaponry for its age.

The 1945 bomb’s parts were likewise prepared in Los Alamos, then transported to the Jornada del Muerto where the first nuclear weapon in human history was assembled and detonated. It was also the height of weaponry for its age.

This first bomb was called “Gadget,” a plutonium implosion device, like the one that would be dropped on Nagasaki, slightly different from the uranium bomb detonated over Hiroshima. This seminal test in New Mexico happened on July 16, 1945, and the question some physicists asked — will this cause a chain reaction destroying our entire world? — was answered. The world was not destroyed and nuclear weapons were dubbed a useful tool for military action. August 6, 1945, Hiroshima was hit first followed three days after that by Nagasaki, two names of Japanese cities that will not be forgotten. The third name is Jornada del Muerto, the Trinity Site, one of the key points of the triad that made this particular end of the world possible.

If time is as thin as I sometimes think it is, I imagine people carrying Clovis weapons along an Ice Age lake that summer morning before dawn, their hands shielding their eyes from this sudden, early sunrise. The explosion happened in the dark while stars were still out. It is said that the mountains surrounding these basins lit up as if it were daytime. This is where a new and dangerous era began, and we forever live in its shadow.

Photo: Trinity Site aerial

This lighting of the hills coincided with my birth. I became un- dead on that date. I have ever since been a subject and student of that event, including some time in the PU lab at Lawrence Livermore.

My Uncle Pino and George Perry from Hondo were erecting a windmill on the site when told to leave because of an ammunition delivery. Upon return, all was materials where dissolved into fragments.

I was born in Whitehaven, England, a few years later in 1951 while my father was working at Windscale, now Sellafield, billed as an experimental nuclear power plant, but in reality, a plutonium factory, Britain’s Hanford. It’s a wonder I don’t glow in the dark. I plan to visit Hanford this summer. Thanks for writing.

There is nothing like growing up in the nuclear age. My elementary school, Crystal River, had nuclear drills. We lived within a 25-mile radius of the Crystal River Nuclear Plant. We sat lined up along the hallway walls, arms covering our heads. As if that would do any good. The drills stopped when we began chanting: “Put your head between your knees and kiss it good-bye!”

During the summer, my friend Michelle and I rode bikes through neighborhoods emptied by snowbird migration, singing that it was the end of the world and we were the only ones left. My nightmares were echoes of The Day the Earth Stood Still, brought to reality by the map I saw on the police department wall – the radius circle of the power plant and our small coastal town together, a target.