This essay originally appeared in 2012.

If the artwork above looks familiar, the reason might be that it was part of the argument that Ann made in a recent post. She suggested that the beauty of the Florentine paintings of the fifteenth century—“stunning, literally; you look at them and can hardly breathe”—couldn’t have been due only to the usual reasons that art history texts cite: Florence’s return to a leading role in international commerce combined with the rise of humanism and rationality. The intensity of the beauty, Ann argued in both words and images, must be due to the intensity of the catastrophes that recently had befallen Florence: the flood of 1333, the financial collapse of 1346, the drought of 1346 and 1347, and finally, in 1348, the Black Death.

No argument here. Or, I should say, no argument with Ann. But the final work of art in her argument, Sandro Botticelli’s 1489 Annunciation, prompted me to think about not only where fifteenth-century Florentine art came from but where it would lead. More precisely, what got me to thinking was the window in the painting.

A hundred years after the flood of 1333, the Florentine architect Filippo Brunelleschi was inventing linear perspective, from the Latin perspicere, “to look through.” Perspective was one more novelty in an age of novelties, but it was in many ways the defining one. For a world full of new things to see—rediscovered ancient texts, ocean voyages to distant lands, distant lands that overturned the teachings of the ancient texts—the artists of la nuova arte created a new way of seeing. They took a two-dimensional surface, applied the principles of geometry, and discovered a way to represent the workings of the three-dimensional world. In their hands there vanished the sacred backdrop of old—the golden or black curtain against which angels and Virgin, saints and Savior, had enacted their symbol-drenched dramas. Instead what stood revealed, receding to infinity, were the details of everyday life: walls, doors, windows, and what you could see through them: trees, water, sky.

Yet as brazen as the artistic breakthrough happening in the streets of Florence—the tricks of the eye that Brunelleschi and his disciples were executing so that, in the words of one awestruck observer, “the spectator felt he saw the actual scene”—was the insight that had to accompany it: that there was a curtain to part.

The uniform backdrop of old was a presence that didn’t fully reveal itself until it was absent. Only then did it yield its secrets: how it had represented an unwavering, unthinking assumption; how its uniform surface of gold or black provided a sensibility unto itself; how that sensibility reflected a singular point of view—saints of a certain size, Madonna of another, Jesus of a third, all arrayed according to a hierarchy that could belong only to the mind of God. But now it was gone, and what replaced it was a point of view that could belong only to the human eye—and only to an eye seeing the world as if for the first time.

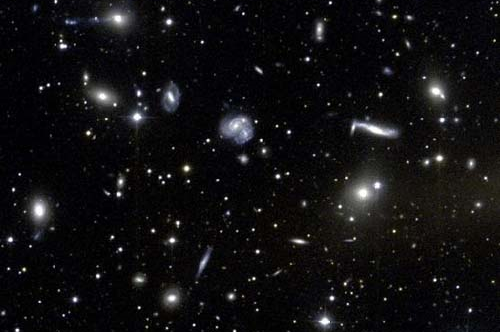

Or, if you were Galileo two centuries later, in 1609, holding in your hand an instrument that you had christened a perspicillum—a perspective tube, or what we would call a telescope: an eye seeing the universe as if for the first time.

To quote Ann: “I’m going to make an argument here, but I’m not going to make it with words, I’m going to make it chronologically and visually.” I’ll begin where Ann began, with Simone Martini’s Annunciation from the flood year of 1333, and I’ll end with a view from a telescope named for a scientist who once made the argument I would make, if I had to make it with words: “The history of astronomy is a history of receding horizons.”

Richard, your restatement of what I said was better than what I said. I love this post.

Thanks, Ann. And thanks for the inspiration.

Did you get the image of Martini’s Annunciation from the Google Art Project?

Gail–I think I got it off Wikipedia.

and the history of this astronomer is a history of receding hairlines

Have you read “The Swerve”? It connects.

This is a beautiful piece.