From the collection of Marcy Friedman.

This post first appeared in March 2021. My longing for more spontaneous museum visits continues.

A little over a year ago I made an unplanned trip to the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento. I had driven to the city to run errands but then decided to go look at art instead, a moment of pre-pandemic spontaneity that felt indulgent then, and now, I imagine, would feel like intense catharsis. It was a rainy Sunday; I remember stepping over crushed magnolia blossoms on the wet pavement. I paid my admission and declined the headset tour, bought a cup of coffee in the museum cafe and drank it in the light-filled glass atrium, a relatively recent expansion of the oldest public art museum west of the Mississippi River.

I enjoyed all of the exhibits, more or less, but one installation made such an impression on me that I still think about it: A collection of 1st-6th century Roman glass jars, flasks, juglets and perfume bottles called amphoriskos. The placard by the case was succinct, noting only a few physical details like “turquoise twin handles, spiral and zig-zag trailing,” and “globular sprinkler with pinecone.” It didn’t say anything about how the glass was made, where it was found, or how the donor, a local painter, acquired it. I left the museum without asking, not realizing it would be the last time I’d visit.

During the pandemic lockdowns, my curiosity sharpened into something like longing, as if those ancient perfume bottles could hold all the other things I miss. Luckily, I recently found a book, “The Marvels of Glass Making,” by Alexandre Sauzay, which answers some of my questions about the Crocker exhibit. Most of the Roman glass vessels that survive today remained intact because they were buried in tombs; Romans were often cremated and interred in glass urns, then buried with amphoriskos (small, two-handled jars used to hold perfume and cosmetics) drinking glasses, and small jugs called juglets. Sauzay describes the origins of many glass-making techniques in his book, including the invention of spectacles, thermometers, microscopes, and telescopes.

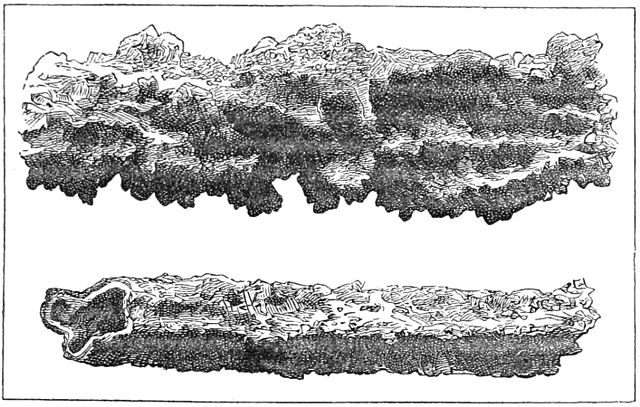

Glass is made of molten silica, which exists in rock, crystal, and sand. It can form naturally when lightning strikes a sandy beach, forming weird, dendritic glass tubes called fulgurites, or when lava rapidly cools into obsidian. I’ve always thought of obsidian as black and shiny, but I’ve learned that it can also be silver, red, or rainbowed, depending on what minerals are in it.

When humans started making glass, they quickly learned to change its color by adding metals and minerals like lead and antimony. It’s likely that people invented glass several times in different places; archaeologists have found cuneiform instructions for making glass written on clay tablets in Mesopotamia that date back over 3,000 years, and evidence of independent glassmaking techniques in Nigeria over 1000 years ago. Pliny the Elder attributes the discovery of Roman glass to Phoenician merchants who were cooking a meal on a sandy beach: When they accidently exposed a combination of alkali and sand to fire, he writes, it “produced transparent streams of an unknown fluid… and such was the origin of glass.” In 79 AD, Pliny was sailing off the coast of Italy when he saw Mount Vesuvius explode. Instead of steering his ship away from the volcano, he died attempting to rescue his friends, described in two extraordinary letters by his nephew, Pliny the Younger.

Looking at the Roman glass and reading about Pliny the Elder reminds me of my grandfather, who died of cancer when I was a teenager. Whenever he had to go into the tomb-like tunnel of an MRI machine or get radiation treatment, he’d recite poems he’d memorized: Shakespeare, Donne, Blake. I like to think he was filling his mind with the things he wanted most to take with him; surrounding himself with precious objects in preparation for some kind of afterlife. Decades later, it is my memories of those poems that survive, fragile but still-lustrous, in his voice.