I’ve been interviewing an archeologist who’s famous for “sticking close to the data,” that is, not saying anything he can’t back with actual evidence. Reminding me of what I learned in my first year as a junior high school teacher: don’t make threats you can’t carry out, and that’s not as much a digression as you’d think. Anyway, sticking close to the data is a great scientific desideratum. You do get the occasional scientist who takes two facts and spins them into great theoretical scenarios. Reminding me that two swallows don’t make a summer, and this also is not a digression. To get to the point here: as a science writer, I’ve learned how good scientists think, and the ones who go off the rails and make claims they can’t back? I don’t interview them, I quietly disdain them. Which doesn’t mean I don’t go off the rails myself, every chance I get.

The latest instances are with just this one archeologist. He’s a specialist in the indigenous people of the Americas, particularily the prehistoric ones. He’s not especially interested in when and how the first people got here but I pushed him to tell me the theory: “You’d expect a dribble of people” he said, “a few 100, ten to twenty to thirty every few decades. They [cross the Bering Strait into North America] and head out and become isolated. Once they drift into a huge landscape, they get isolated.”

Oh oh oh! Small groups of people, huge landscape, getting isolated! Because I’d heard from another scientist who was pretty sure he remembered that the Pacific Northwest had an unusual number of indigenous tribes. I immediately had a theory: the number of tribes was so high because 18,000 years ago, the first people came over in families and in those hundreds of miles of continental coast, didn’t run into other families and grew into separate tribes. Note that I’ve got a full-fledged theory based on one piece of data — a scientist’s vague recall — and my stunning logic. Anyway I interrupted the archeologist and told him my theory and hoped he’d say he’d just been reading a study detailing exactly that. Instead he paused for a minute, then changed the subject; and in that minute, over the phone, I could hear him roll his eyes.

Ok, so much for that one. But I’m not discouraged, so how about this one? The same archeologist wrote that several centuries ago a local tribe in Chile lived in the Andes Mountains, in the central valley, and on the coast. I instantly have a theory: they couldn’t have. I used to live in the central valley between the Appalachian Mountains and the Atlantic coast. The valley people were farmers and small businessmen; the coast people were fishermen or filthy rich; I haven’t a clue what the mountain people did except that the valley people called them bad names. Those were three very different cultures. So my theory is, people who live in different places are different people and have different lives; they are not the same tribe at all.

This theory, my only datum is a broad and so-far unsupported observation of local culture, plus some more stunning logic. So my problem now is, do I ask the archeologist about this theory? Or since he’s still talking to me, should I just leave well enough alone? Drop it, Annie? Reminding me of the lady up the street whose dog loves acorns and she thinks that’s not good so she’s trained the dog to drop them, and in this acorn season the two of them walk up the street with her saying, “Drop it, Coco” and Coco going “ptooie, ptooie.” Now that really is a digression.

My real problem is less whether I ask the archeologist than whether I should stop going off the rails. It’s such a lovely little rush, that little springy “oh! hey!”, entirely addictive. I suppose, as long as I don’t go spreading it around as the God’s truth, it’s harmless.

I do want to advise you, though, that if you see a scientist or a science writer running around loose, issuing great proclamations with sparce evidence, you should pat them on their little heads, be happy for their unsupported joy, and not believe a word of it. Go about your business as if they’d never spoken.

_________

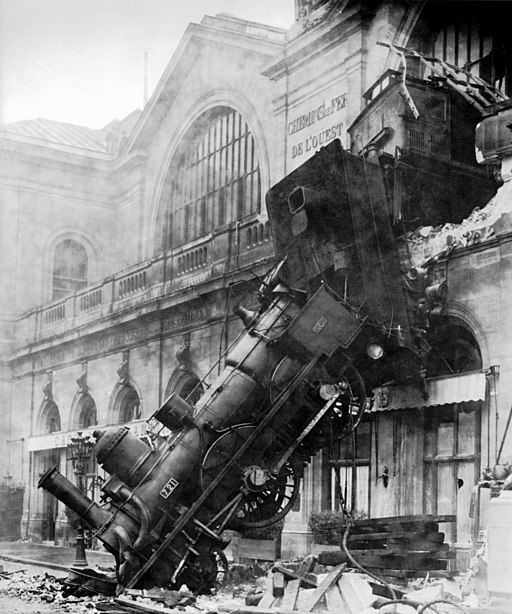

Photo: via Wikimedia Commons

Delightful…fascinating. That said, would or will be interested in how an AI chat bot would extend this perspective, with or without digressions. Just wondering. And, I will still prefer your written wonderings.

Thank you! My understanding (big caveat right there) of AI is that it’s only as good as its training set. So its digressions wouldn’t have included my memories. I’m delighted that you still prefer the real thing. So do I.

Another good one, Ann.

Mille grazie, Dale.

I love when some connection goes off in my brain — and I equally love when the scientist I’m interviewing goes there with me. I’ve certainly been met with disdain in the past (and then I worry that my interviewee no longer trusts me as a reliable reporter). But I’ve also had researchers say, “Oh that’s interesting! We should try to look into that.” Which makes the exercise worthwhile and the risk of disdain nearly moot.

I had the same experiences of both kinds, and I love it when the researcher say “Oh that’s interesting.” I just need to keep reminding myself of my remit — I’m the writer, not the scientist. I can use my own questions to understand the research, I can’t fall in love with them. I know you know this.

“[R]unning around loose, issuing great proclamations with sparce evidence” has become a national sport not confined to the [playing] fields of scientists and science writers.

Excellent point. A hard-earned lesson for me in those first years of reporting.

(Meaning: I totally made that mistake – the falling in love with a source and relying on them too much – early on.)

Oh I meant, falling in love with my own questions and theories. Unclear referrent there. Falling in love with a source is an entirely different matter and will not be discussed publicly but will be avoided like the plague, the plague I say.