Introduction

I hate flossing. My mouth is small, my teeth crowded, the spaces between them difficult to reach. Twice a year, my dental hygienist entreats me to floss more frequently. Sometimes I assent, and mean it, and actually manage to make it work for a few months until I invariably get sick or injured or burned out and jettison all nonessential tasks. Sometimes, especially during hard times, I just tell her no.

I left my last visit determined to try again. At home, I got out markers and paper and drew a shaky grid (see Fig. 1), then affixed the chart to the back of the bathroom mirror. I told myself that I would start small, flossing two days a week, and reward myself by adding a little heart sticker to the chart each time I actually did it.

It’s been months now. I haven’t missed a flossing day since.

The heart stickers are identical and plain, yet I derive tremendous satisfaction from affixing one to its messy square on the chart. The package of 1,810 stickers cost $4.99, or about $0.002 per heart. For less than two cents a month, I’d tricked my brain into actually wanting to do something uncomfortable, boring, and gross.

(You know where this is going, right?)

I wanted to find out why.

Background

As it turns out, scientific literature is brimming with studies on stickers and the brain’s reward circuit—but only in small children. I searched and searched and did not turn up a single paper focused on stickers and motivation in adults. If anyone was going to get to the bottom of this, it was going to have to be me.

Methods

I created a qualitative study: a short survey, distributed via a link in my newsletter and on social media. My sample size (N=20) was meager* and selection bias was significant: all participants are part of my extended network and, more importantly, the kind of people who would volunteer to take a survey about stickers.

Results

Of this self-selected pool, 73.7% of respondents were sticker people. Within that group, 40% reported using stickers to motivate themselves. Sticker-linked tasks included eating vegetables, exercising, drinking water, eating mindfully, and making the bed.

Here’s what else I found out.

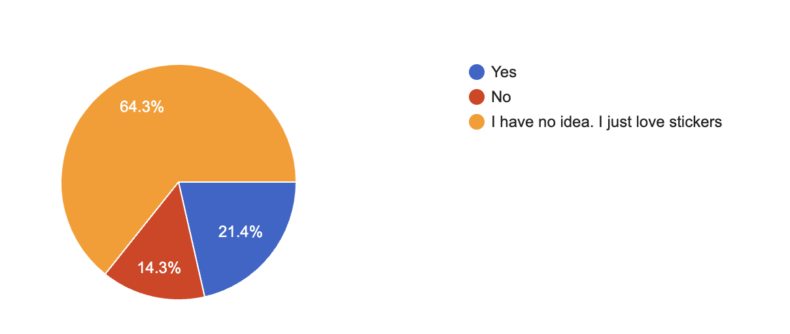

QUESTION: Do you think stickers actually work to motivate you?

QUESTION: Why stickers? Why not something else?

“Good question,” one person said. “I don’t get it.” Another: “Absolutely no idea.”

Some respondents theorized that stickers work because they are immediate, small, and ephemeral (“You can affix them as part of the face you’re showing to the world…today”), while others suggested the opposite. “It’s physical evidence that lasts for others to see and as a reminder. A high five is gone after the slap.”

“I never was a student who teachers gave those gold stars to,” one person said. “I’m making up for lost time.”

QUESTION: How do you feel when you get a sticker?

“Childish and childlike,” one respondent wrote. “Good,” said another. “Shiny.” “I don’t do this a lot but I think it would bring a lot of childlike joy.” “Like I’ve achieved closure.”

Then there was the response that made me tear up.

“Like the kid I wanted to be,” they wrote. “Happy.”

Conclusions

I came away with few answers and new questions:

- Do children whose parents use sticker charts grow up to be sticker chart users?

- Are sticker charts an American thing?

- Is it generational? Cultural?

- Do sticker people stick together?

- Are neurodivergent adults, who are often quite skilled at adapting and hacking their own executive function, more likely than others to enjoy and use stickers for expression, motivation, and reward?

(As a neurodivergent adult myself, I have a pretty solid guess on that last one.)

Major themes included pride, nostalgia, creativity, silliness, and caring for one’s adult self by nurturing an inner child. Reading the responses, I felt washed in warmth and tenderness toward these dear humans doing what they can to treat themselves lovingly in this raging, painful world.

My questionnaire did not (could not) answer my question. It was the wrong tool for the job, and I am the wrong person. I am no closer to understanding the cognitive mechanisms that transform a loathsome task into the prelude to a $0.002 thrill.

My brain continues questing. But my heart is full.

Postscript

The final “question” of the survey offered participants a menu of virtual stickers and invited them to select as many as they wanted. The list included two types of gold star, a sparkly heart, a rainbow, a lobster, a cool skateboard, and a worm. Most respondents (82.4%) wanted the lobster. Very few selected the worm.

I don’t know what to do with this information.

*

Figures by me.

*An N of 20 is pitiful, and it is still larger than the sample sizes of many overhyped studies on human health, especially those involving food or weight. Trust no headline.

If you like sticker charts—or, for that matter, if you don’t—please check out Finnegan Shannon’s Bingo For Doing Something You Dread. https://syllabusproject.org/bingo-for-doing-something-you-dread/

My wife is an inveterate sticker person. When my daughter called with some especially good news about an upcoming surgery, my wife walked around the garden center where she works and gave everyone a sticker – employees and customers. She even put a sticker on the mail carrier’s badge. Yes, she keeps pages of stickers in her work locker. Yes, everyone felt brighter that day.

I think you’re on to something.

Oh, I just *love* this. Please tell your wife she’s brightened my day, too.

Kate: I think this is the best LWON in months, if not years. A rich contribution. I just put my “I Voted” sticker on to my motorcycle. I miss those “I was very brave” bandaids they used to give me when I got shots, and I always ask for one when they draw blood. No luck yet! I too am a flosser hater, so I would like to pass your article on to my dentist. They must get tired of their reprimanding. I thought I was the only one….

Thank you, Chris! I had no idea how this post was going to land for people, so it’s great to know it resonated. I bring my own special wacky bandaids whenever I get a vaccine; it’s not quite the same as getting a sticker from someone else, but I do still walk out of there with my head held high and a cute jellyfish on my arm. I also usually bring a few extras so the people behind me in line can have jellies too, if they want.

“I also usually bring a few extras so the people behind me in line can have jellies too, if they want.”

I don’t know if I’d wear a jellyfish bandage (I don’t know that I wouldn’t, either), but this makes me like you so much!

I don’t use stickers as a motivator, but I do like the damn things. Sometimes when I get a new one, my wife will ask, “How old are you?”, and I’m never sure how to answer. “But look, it’s a trout!” only makes her repeat the question…

I hope there is some consolation in knowing that we, the adult sticker lovers, are legion. I think I have a salmon sticker somewhere in my desk, but no trout, so good on you.

Vital update, Mark: A friend just gave me a trout sticker (plus lots of other fish)! She didn’t even know I wanted one! I am so blessed.

Yay!

Update for you (actually just something I neglected to mention last time): my most recent sticker, a nice Jurassic Park one, was given to me by my wife, so she isn’t actually anti-sticker.

And she raises another topic for research and discussion: how many of us immediately apply stickers to objects, and how many of us instead accumulate them because we are too reluctant to commit a great sticker to what might seem like the right object now but might later prove otherwise? And what does that say about us psychologically?

Yayyy supportive sticker spouses! Pro tip from one of my sticker friends: you can buy sheets of flexible refrigerator magnet material pretty cheap at the hardware store or online. Slap a sticker on there, cut it out, and bam: reusable sticker!

I used to teach in a HS inclusion class (I was the SpEd teacher), and I used stickers as an “on task” immediate reward, students poo-pooed them at first, but within a week or so, would get upset if they didn’t get one when I walked by their desk. These were 10-12 grade kids!