Lately I’ve been lingering in Bortle 1 zones, rare dark places untroubled by human lights. On the scale, 1 is where your eyes discern the faintest satellites and the fuzzballs of nearby galaxies. When you wake hours before dawn, the atmosphere lacks the flashing planes, and sometimes satellites seem to have fallen asleep. The stars appear numberless.

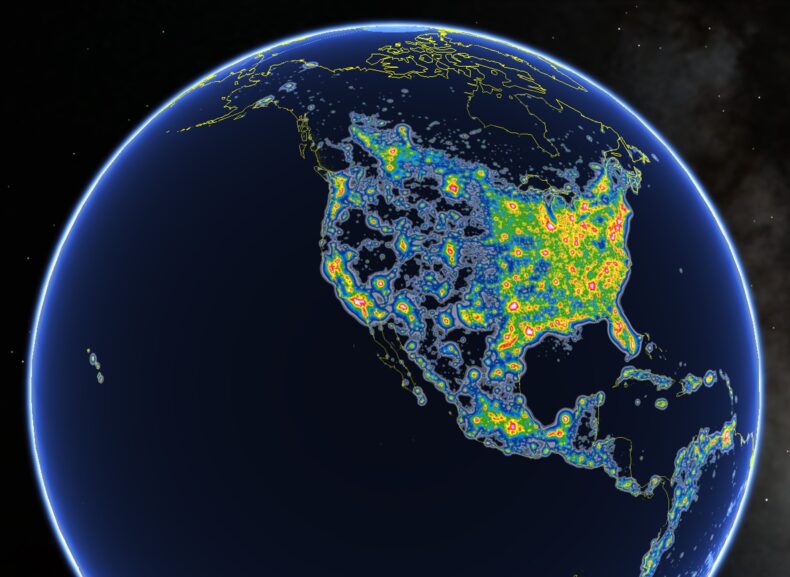

Bortle scale, measuring night sky darkness, goes from one to nine. Nine is mostly starless, and city-lit, lemon-colored or blazing white. Among the many celestial bodies up there – about 5,000 stars visible to the unaided eye at most, along with nine galaxies, and thirteen nebula – the only dependably visible ones are the sun and moon. Think Las Vegas Strip. On the other end of the spectrum, a Bortle 1 reveals a faint blue glow of sunlight scattered across space by interplanetary dust, called zodiacal light, or ‘false dawn’. Clouds form a black vacancy as they pass against stars. The darkness seems as if it casts a shadow.

In September, I rowed through Cataract Canyon on the Colorado, a blob of Bortle 2 in southern Utah with a Bortle 1 center. For eight days we passed below desert buttes, no town or settlement on any horizon. We camped in cliff bends where sandbars gathered at the outside sweep of bowknots, and around the fire told stories and talked about the sky.

As the river carried us southwest, about 65 miles from Moab, Utah, and out of range of its most distant glow, we entered the Bortle 1, though from the canyon bottom, a couple thousand feet down through tiers of boulder slopes and sandstone palisades, I don’t know if I could tell the difference. A few of us were left at the fire, then two, then none. Instead of going back to my camp, I walked alone to the river, and as my eyes adjusted, I took off my clothes. We’d entered the new moon, sky as dark as it gets. Cool, muddy swirls of river came up around me as I waded under a ribbon of stars and the zodiacal light filtering from space. The canyon seemed to hum with darkness, cliff walls pure black.

The Bortle scale, created by amateur astronomer John E. Bortle, came out in 2001 in Sky & Telescope magazine. Scientists tend to shy away from it, finding it more subjective than quantifiable, the number depending on the acuity of the naked eye, but it gives a good sense of what sky you’re under. At Bortle 1, certain parts of the sky and the Milky Way cast a visible shadow. A Bortle 2 horizon is faintly illuminated, the Milky Way looks like an articulated spine, and clouds are seen as “dark holes.” Three is a rural sky with details visible in the clouds. Four and five bear the last zodiacal light. At six, the only Milky Way to be seen will be directly overhead, and seven turns the sky gray. Eight is bright enough to read by without additional light, and a few constellations can still be picked out. Nine, you might see Venus or Jupiter, and the star Sirius in canis minor if you’re looking right at it, otherwise, it’s easy to forget space is out there.

At the end of September I camped with my wife and parents in a cathedral cove, one of many along the fluctuating shores of Lake Powell near the border of Utah and Arizona. This is a patch of Bortle 1, though we had moonlit nights, powder milk floodlights beaming through gaps in cliff walls, turning stars several notches down. The Bortle scale, at least its lower numbers, only works when the moon is a sliver or gone entirely.

Some of these past two months I spent at home in southwest Colorado, a spot of Bortle 1, though larger towns 50 and 60 miles away are pressing on that number. This time of year, nights getting cooler, bugs down, I prefer sleeping outside. Lying on the deck with me, my wife called the Milky Way a galactic chiropractor, spread above us in its autumnal glory. She went back to bed and I slept out there in my bag, waking now and then to blink at a Van Gough canvas of blues, purples, and blacks. With the moon waning toward its new phase, I could see the diffuseness of zodiacal light, and also reflective arcs of countershine, called Gegenschein, a backscatter that lies opposite the earth from the sun. This is the result of gravity between Earth and the sun forming a stable gravitational zone in space where interplanetary dust is more concentrated, thus shining back more light.

With most of human population on Earth living in Bortle 6 or higher, it’s a blessing to get these doses of dark skies. A few months back I was talking to Rebecca Boyle, one of the writers at LWON, and author of a new book on the moon that I’m excited to see. We were talking about skies and she said she felt like during the daytime we see the sky, meaning the atmosphere, while at night we are not really seeing the sky. We are seeing space. I love that idea, that only at night do we see what is truly out there.

Now, we’re heading back toward the new moon phase, full having passed a few days ago. Each night becomes successively darker. By new, I will be halfway through a 200-mile bike trek in southern Nevada, taking back roads through remote saline basins, camping with a friend in the middle of nowhere. We’ve planned to have no campfires and to only use red, green, or blue lights rather than white, preserving our night vision. The plan is to bike out of Las Vegas, starting on the strip, and count our way down through Bortle scale, leaving the sky and tumbling into space.

One of the most awesome places I’ve been to “see” Nevada, both earth and sky, was at a place called Burnt Cabin Summit, about 20 miles +/- southwest of Austin, NV. At night, the sky is carpeted with stars; the Milky Way a thick pathway cutting through a meadow. During the day, the desert spread out in undulations of sagebrush waves. I realized that’s why the Great Basin is sometimes called The Sagebrush Sea.