I’m on a backpacking trip this week, which makes it as good a time as any to revisit one of my favorite posts (or, more accurately, to make you revisit it). Although Colorado, our home since early 2022, doesn’t have quite the same abundance and diversity of rentable Forest Service fire towers as did the Inland Northwest, we still hope to rest our bones in a couple of these aeries next summer. Hopefully they’ve updated the menu since I whipped up a batch of Shipwreck in 2020.

When, years from now, I reflect on the debacle that was 2020, I will remember it for COVID, of course, and for its possibly planet-saving election; but I will also recall it as the Year of the Fire Tower. Decommissioned fire lookout towers stipple ridgelines across the West, many of which can be rented for a $40 nightly fee — a sensational bargain, as long as you don’t mind carrying your water up fifty feet of rickety stairs and sleeping on a mattress strewn with mouseshit. Elise and I spent this summer bouncing up derelict dirt roads to towers with names like Cougar Peak and Gird Point and Yaak Mountain, seeking solace in sunsets and the stoic profile of the Northern Rockies. As I wrote recently for CNN: “Being surrounded by millions of years of rugged geology doesn’t diminish our present crisis, but it does offer a bit of deep context.”

I’ve come to love fire towers not only for their scenery, but for their history. Luminaries like Gary Snyder and Ed Abbey once scanned horizons for smoke; Jack Kerouac suffered an emotional meltdown during his summer at Desolation Peak. Traces of antiquity still survive at some towers: initials carved into cement foundations; lichen-encrusted cairns; the wondrous Osborne Firefinders that dominate the tiny cabins like supermassive stars. In one tower we unearthed a copy of the Fire Man’s Handbook, a 1966 manual whose wisdom included this pearl: “When lightning storm is near or overhead, observe the following safety rules: Stand on insulated glass-legged stool.”

If lightning didn’t kill twentieth-century lookouts, the food might do the job. Lookout cuisine was, by all accounts, abominable. Fire-watchers depended on the canned, the powdered, the non-perishable: anything that could be hauled in on a mule and preserved without refrigeration. One early cookbook advised lookouts to “purchase a half or a whole mutton from sheepherders in the vicinity of your station. To keep, hang up in a tree or some other high point at night, wrapped in canvas, or put in a burlap sack during the day and put between blankets and mattress of bed.” No wonder towers were often ransacked by bears.

Fire tower food was so notoriously terrible that it inspired a Colville National Forest lookout to pen the following bit of doggerel, in which FS stands for Forest Service:

I like FS biscuits;

think they’re mighty fine.

One rolled off the table

and killed a pal of mine.

I like FS coffee;

think it’s mighty fine.

Good for cuts and bruises

just like iodine.

I like FS corned beef;

it really is okay.

I fed it to the squirrels;

funerals are today.

***

One afternoon this summer, while camped in a tower near Hamilton, Montana, we dug up a dusty document that validated the abysmal reputation of lookout food: The Lookout Cookbook (U.S. Forest Service, 1954). The 1950s have always struck me as a rough culinary decade, a casserolic wasteland of TV dinners and tuna noodle surprises. The cookbook, we quickly realized, combined the era’s tendency toward bland mush with the manifold challenges of preparing and storing provisions in a remote, climate-uncontrolled setting. Flour, potatoes, onions, and canned beans abounded. The book contained not only recipes, but dubious life-hacks for rendering stale goods palatable: “Tough meat may be made tender by pounding, slow cooking, or allowing it to lie a few minutes in vinegar water.”

We leafed through the pages. Every dish was more questionable than the last. There was a section titled “Fish,” whose offerings included salmon loaf, salmon cakes, creamed salmon with peas on toast, and something called, horrifyingly, a salmon wiggle. There was a page of sauces: brown gravy, cream gravy, cheese sauce, and Quick Tomato Cheese Sauce. There were desserts: maple custard, caramel custard, boiled custard; rice pudding, bread pudding, cornstarch pudding. Many baked goods were topped with something called “boiled frosting,” while others called for sour milk:

To sour milk:

1) open a can of milk, let it stand where warm until sour.

2) A teaspoon of vinegar in ½ cup of milk will sour the milk instantly.

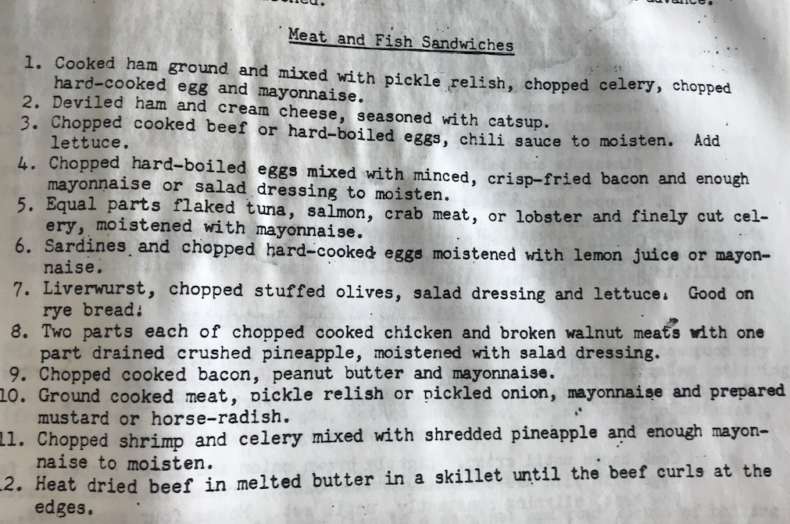

And the less said about the sandwiches, the better. Suffice to say that “Deviled ham and cream cheese, seasoned with catsup” was one of the more appealing options. Or how about a classic BPBM — bacon, peanut butter, and mayo?

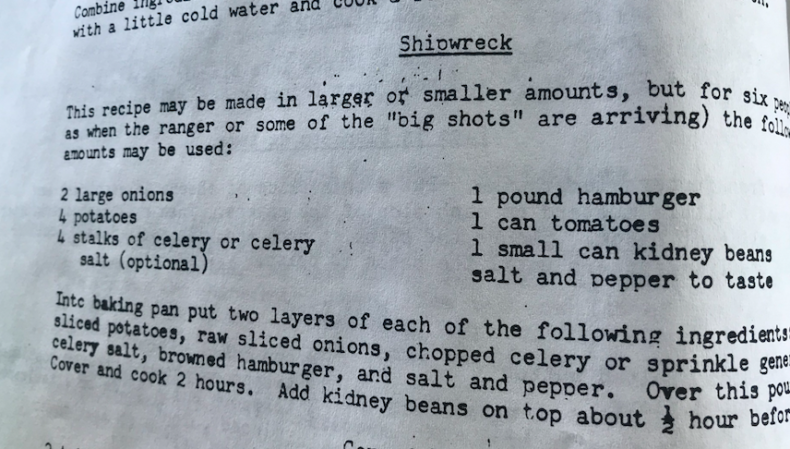

This week, seeking to revive warm summer memories, I decided to finally sample the Lookout Cookbook’s wares. Although I’m as adventurous a gourmand as any, boiled frosting and salmon wiggles were bridges too far. I decided to play it safe and whip up a concoction known only as “Shipwreck,” a colossal meat-and-potato stew. Shipwreck, the cookbook claimed, was a surefire way to feed a large crowd, “as when the ranger or some of the ‘big shots’ are arriving.” No ranger seemed likely to show up on my doorstep in Spokane, but I was determined to impress my wife.

Shipwreck shared the same fault as most 1950s fare: it seemed destined to be utterly insipid. The recipe, written in an epoch that predated the advent of luxuries like “spices” and “seasoning,” called only for “salt and pepper to taste.” That would never do. We poured a full beer (a Belgian-style white from Alaska Brewing Company) and most of the contents of our spice rack into the stew, and let it bubble away for two hours. (I also substituted bison meat for the hamburger.) I’m grateful to live in the age of cumin, coriander, chipotle, and cayenne.

Thanks in part to this flavor augmentation, Shipwreck hit all the right spots. The stew proved filling, hearty, and bone-warming, perfect for an early winter evening. To my astonishment, I realized I’d happily make it again.

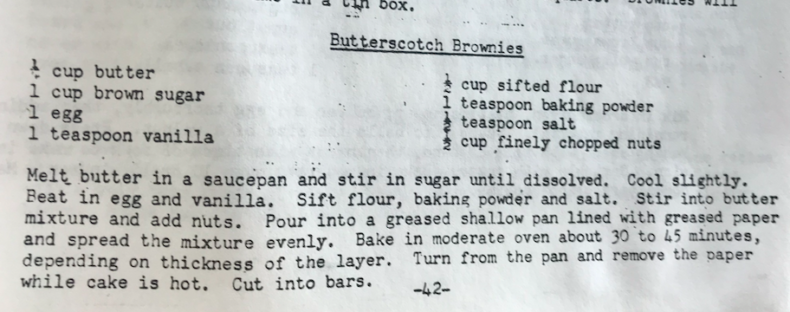

The second recipe was less successful. For dessert I whipped up a batch of Butterscotch Brownies, which, I soon learned, were basically moist blocks of brown sugar. As the recipe didn’t call for cocoa powder, and the tough, buttery briquettes emerged from the oven the color of wet sand, Elise disputed that they were actually “brownies,” an epistemic dilemma that, a day later, we’re still contemplating. What is a brownie, anyway? Whatever your definition, the Lookout Cookbook’s interpretation wasn’t half as appealing as the brownies on any number of foodie blogs. Maybe these impostors would’ve been more appealing topped with a nice warm swirl of boiled frosting.

Despite these mixed results, I’m willing to give the Lookout Cookbook the benefit of the doubt. After all, suburban comfort is the wrong context in which to consume its haute cuisine. The Lookout Cookbook was intended for a different era, and a more spartan setting — one of deprivation, austerity, and simple pleasures. It was easy to imagine shoveling down a bowl of Shipwreck in a tiny aerie high above the Bitterroot, the chill night wind whistling through the loose panes, a fire crackling in the woodstove, cheeks flushed from a long day of chopping wood and breaking trail. In that environment, Butterscotch Brownies would no doubt have been a luscious luxury. Long live the Lookout Cookbook, evocative guide to a lost culinary era.

Below, some gnarly sandwich suggestions from the 1954 Lookout Cookbook — if you dare. And if you’re a veteran lookout yourself, I hope you’ll share your favorite recipes in the comments.

Thanks for making me laugh. I presently live in a suburban storage unit and can empathize with the cooking dilemma. (No website. I’m on Facebook, Instagram, and Google Maps reviews. My Twitter account was highjacked.)

I enjoyed this piece, esp the cited poem about Lookout fare. It reminded me of a FS experience I had in 1976. Although a surveyor and not a firefighter, I’d work in fire on weekends to make a little extra money. There were C-Rations at the station that we could help ourselves to. Even fresh, homemade Holiday fruitcake is often the butt of jokes, but it is foodie-worthy compared to a C-Rat fruitcake that is nearly as old as I was (22 at the time). An epicurean low point, to be sure.

Maybe I spent too many years working on a trail crew and packing a lunch of Jiffy and crystallized honey on stale bread, but I would eat every single one of those sandwiches, with the exception of No. 7.