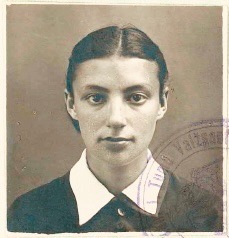

Under a spring sky in the high desert of Western Colorado, we had a little gathering at our house. My wife’s childhood friend, awarded author and translator of Lithuanian poetry Laima Vince, stood on our wooden deck discussing a Jewish poet who was executed along with her family at the age of 19 in 1941 outside of the small Lithuanian town where they lived. Laima translated the young woman’s work into a beautiful book, including reproductions of journal pages revealing a swooning love life complete with teenage heartbreak, ink on two of the pages dotted with three drops of tears.

Matilda Olkinaitė’s journals and poems were hidden in a church and hardly seen by anyone until they were unpacked from a dresser and shown to Laima in 2017. Otherwise, they would have easily disappeared, and the young poet’s name would be lost. As war rose around her, the poems became dark with premonitions as, Laima wrote, “she wished she could bring the world back to its senses.” Less than a year before she was murdered and buried in an unmarked weedy peat bog, Matilda wrote:

It is so difficult for me. I wish I could utter that one word.

Just one word for the crowds and for the nations.

The processions would pause. Time would come to a halt.

All the generations would stop and listen.

Several months ago, my wife Daiva and I traveled to her family’s homeland in Lithuania, where she’s been returning since she was a teenager when the country was still under Soviet occupation. As we drove the countryside we came on sign after sign indicating a tragedy had happened in one place or another, mass graves where a village burned to the ground, murders unspeakable, concrete bunkers old enough to have become part of the landscape. The numbers of the dead at each site range far and wide; 105, 49, 50,000.

Daiva took me down a gravel road puddled with rain to a place she’d visited before, a haunting and beautiful scene for her. We parked and walked up a hill in birch trees and damp grass where 40-some residents of the massacred village of Ablinga are memorialized. They were killed by Nazis in World War II, fathers and sons, mothers and daughters, sisters, brothers. What was left of them and their village was burned. Trees have been carved into remembrances, and walking through their renderings I felt crushed. In one wooden trunk, a father held his arms around a mother who held onto their two daughters, the youngest turned to face inward as if hiding from something. She had two braids tied with ribbons down her back, now cracked where the wood had split from age. The father’s hands, oversized, as if they could hold off anything, were placed so they made contact with everyone in the family. It was impossible not to cry.

How could I not talk with my wife about her relatives sent by Soviets to Siberia never to return? Lithuania, she said, is between other countries who want to get at each other. Russia is on one side, the rest of Europe on the other, and wars of unthinkable cruelties pass through the middle. We walked from one sculpture to the next under a crisp autumn sky, sunlit breeze bending the grass after a rain.

On our deck at home as Laima read to us in English and Daiva stood to read the poems in Lithuanian, I walked through carved trees in my mind. I saw the people of Ablinga in their best clothes, represented in a moment between normal life and the end, their braids perfect, flowers in hand.

Laima said she’d been interviewing people caught up in the war in Ukraine. A volunteer delivering humanitarian aid and returning frequently through the border to Poland said he saw young women with children who fled so quickly they hadn’t been able to grab passports. Guards at the border told them to go through their phones to see if they had pictures of their documents, and as the women scrolled desperately, he saw the pictures they carried, birthday parties and sunsets, family gatherings, smiling faces. The informant was struck. Life had been ordinary up to the last second.

The last entry in Matilda Olkinaitė’s journal, at a similar turning point, reads,

I passed my exams with a score of 3, but I did not take the grade. I went home. I did not stop at Kaunas. And now I am determined to study hard to quiet my conscience.

While we were in Lithuania, a fresh mass grave of more than 500 people was found in Ukraine, consisting of soldiers and civilians and whole families made nameless in Putin’s war, now left to forensics specialists and DNA to find their names again.

A high-rise in Vilnius, the capitol, bore a huge banner which read PUTIN, THE HAGUE IS WAITING FOR YOU. Ukrainian flags were everywhere.

The loudspeaker in a grocery store announced that there were three Ukrainian colleagues working at the store and they were still learning the language, so please be patient and help them along.

We went out to a whiskey bar one night with a young cousin of Daiva’s who is in the Lithuanian military. He said people in the service are pacifists. They know they will be fodder if Russia takes Ukraine and keeps moving.

Matilda wrote a year before her death,

Long generations carry suffering

From the cradle to the grave—

Suffering immense and deep,

And as endless as the night.

Fall asleep now. It is a long roadThat will lead you into the night…

Go to sleep, I will sing to you,

My tiny baby.

As Laima read to us, giving young Matilda back her voice, a hawk circled the Colorado sky behind her. It came low enough we could see its spread of feathers holding the wind. Laima couldn’t see the bird as she read, but the rest of us, a handful of friends, lifted our faces. Later, Laima said it must have been Matilda, she must have heard her poems being read and come back.

She came back, I hope, to utter that one word that brings the world to its senses.

Ablinga photo by cc; student photo of Matilda Olkinaitė, Rokiškis Regional Museum

Thank you for this story, Craig. So poignant, and also a reminder to us, in this time when it sometimes feels like the world is caving in on us, that history holds catastrophe after catastrophe. The dead leave behind bits of their humanity for us to hold. The resilient carry on, hopefully to remember that their miseries are not the first nor the last.

Deeply moving

Thank you for this, I think. It is so full of many humans desire for war and chaos no matter the cost to others. It is also a wonderful testament to the courage of some.

Beyond heartbreaking… heart shattering…

One of the best posts I have read. We can never forget!

Well said and writen. I watch the marchers at Charlottesville, the singular mass murderers, the thinly vailed hate in speeches from our former President and his disciples around the world and wonder if we will ever come to our senses. My wife is Jewish, from Cleveland. Her grandfather escaped the Pale of Russia and Poland in 1905 coming to America. His wife was Canadian. A story in the family tells how she kept asking to go to Europe. He finaly told her to go, “you go, I’ve been”. She went with some girlfriends and did the grand tour. Grandpa Sam met them all at the end in Israel.

We, all of us, Jews, gentiles, all of us, must never forget. We must also never allow such things to happen again.

as moving and important her words, and your words, Craig – humans seem to be losing the ability to listen, no matter what “word” is spoken. Thank you for sharing what you heard.

Beautiful. I wish I could utter that one word, too! Matilda’s story had additional resonance for me since I’m part Lithuanian–my Lithuanian grandparents arrived in the US in 1948 with my then-2-year-old mother (another Daiva). They had a good life here but also carried a lot of pain, thinking about loved ones left behind whose fates were unknown to them until much later.

Hi Giedra! Good to hear from you. I can’t imagine that kind of pain.