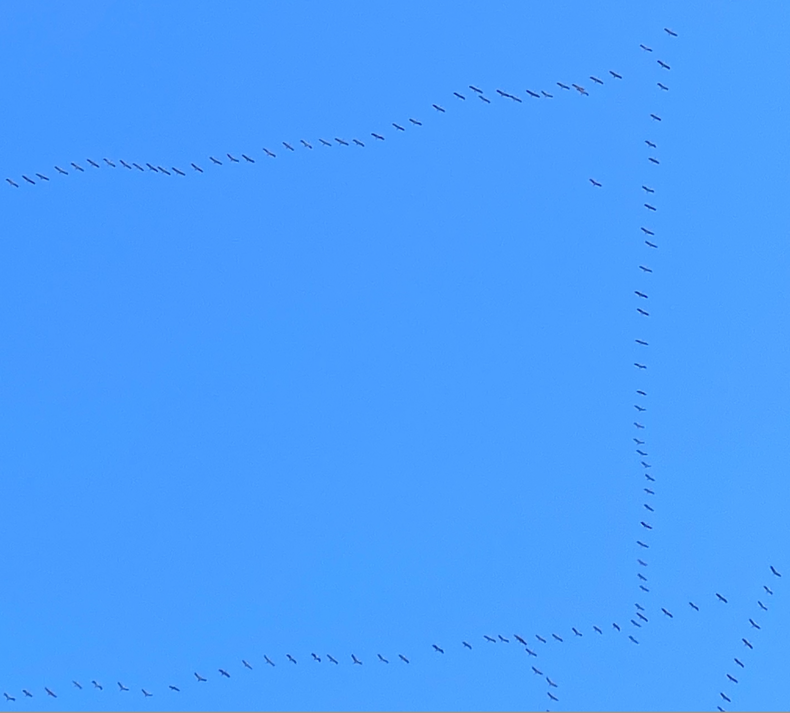

While visiting the Baltic seacoast of Lithuania a couple weeks ago, walking with my wife among hills of half-grassy sand dunes, I heard what I swore were sandhill cranes. I scanned an October sky pillared with distant cumulus until finding giant letters written high overhead, southward V’s and W’s a hundred yards long.

Sandhill cranes was my quick conclusion, though I was wrong. I don’t often travel outside of the Americas, so I was already one lap behind. There are no sandhill cranes on this side of the planet. These were Grus grus, in English known as common cranes, a name that feels underwhelming considering how strongly they must figure every spring and fall. In Lithuanian, they are called gervė, one of the most mentioned birds in Baltic literature and lore.

My sandhills, Antigone canadensis, are American species with some drifting into eastern Asia. They herald the change of seasons, standing together by the tens of thousands along lake edges and marshes on their annual migrations. To me, they are as remarkable as monarch butterflies. Last century they were edging toward extinction, but conservation efforts and changes in attitude where they were not treated as vermin invading agricultural fields has led to their brisk expansion. As they pass through Colorado or Nebraska they are known to gather in the hundreds of thousands, as loud as symphonies of wood ratchets and flutes. These cranes did the same here, coming from as far north as Siberia, flying south as far as North Africa, crowding wetlands and fields that they know like a map.

To verify what I was hearing and seeing, I turned to my wife several paces away and said do you hear that? She paused and when she heard the familiar, faraway prattle, her face changed into a bemused smile. Her mind was suddenly taken home, autumn in ditch country, Western Colorado, the last time of the year she’d be wearing a spaghetti strap outside without getting goosebumps. She’d be squatting in the garden clipping back October die-off when the calls would reach her and she’d shield her eyes from the sun with one hand, searching a prismatic blue sky until she found a great V at 10,000 feet, 3,000 feet above her.

How many times have I watched sandhills flying over the San Luis Valley in southern Colorado, one of their central migratory corridors? I imagined the bright shields of the Great Sand Dunes and the Sangre de Cristo Mountains dusted with their first snow, and overhead cranes spelled out the change of seasons, yet here I was far from home, standing on the Curonian Spit of Lithuania, eye level with Sweden.

When I travel far from home, I find myself looking for connections, ways to bring me back. I trace latitudinal lines around the globe, matching Lithuania to Newfoundland, Winnipeg, and Southeast Alaska. I hear migrating birds and hold them up like an overlay across my side of the world. When I hear cranes pass over my home, watching them kettle on updrafts, my mind is carried, my horizons opened up. I appreciate the freedom of their movement. Rather than roads and borders, they know the land below by its mountains, grasslands, and rivers, a world that to them must seem unbroken.

The European crane — because I cannot for the love of God call them common cranes — is slightly larger than the sandhill, but all in all, voice, flight patterns, physical appearance, they are twin siblings standing on either side of the globe. The traits they share are all but indistinguishable. They are monogamous, forming stable mating partnerships, and their clutches are of no more than three eggs at a time. They share a complex mating dance, long-necked head bobs, legs trotting up and down, wings outspread, each display ending with a vocalization. Same feeding habits, alert patterns, social postures, and altitudinal flight plans. The red cap of feathers on their heads is slightly different in shape, but the same red.

Let’s forget I thought these were the same bird and that like a dumb tourist I wasn’t carrying a bird guide. To be fair, we were here mushroom-hunting, carrying mushroom guidebooks in Lithuanian, focused more on the ground as we headed for a thick pine copse on the other side of the dunes where mushrooms would be springing up through moss. Let’s say I knew these weren’t sandhills passing by every several minutes, a migration that comes in fleets. The point is, I couldn’t tell the difference. They are both unique species, suggesting a long time apart, while their appearance and adaptation tells of shared ancestry and little need to change.

The sound made us slightly giddy, a different shade of light put on our day. Sandhills or European cranes, who would care? We were transported. We walked barefoot, shoes in hand, through dunes a hundred feet tall, some nearing 200, the largest dunes in Europe. The pine copse we were aiming for, where mushrooms came up through mossy duff and soft salads of lichens, was just ahead through gradually descending foothills of sand.

At the edge of the forest, we reached a wooden post painted red and white. A sign stated in multiple languages not to go any farther. We’d reached the demilitarized zone between Lithuania and Russian territory, disguised as the thin band of a fenced wildlife refuge. On the north side was this young country once a republic in the Soviet Union and now part of the European Union, and on the south was Kaliningrad Oblast, Russia. Though dunes and pine copses continued unfazed, I felt like a wall stopped us. The other side leads to Russia’s only seaport below the Arctic. Lithuania, maintaining independence from a threatening neighbor, enforces heavy restrictions on Russia transporting goods from its port across Lithuanian territory, restrictions markedly increasing after Russia invaded Ukraine earlier in the year. This felt like a strange veneer, a human discoloration.

Standing barefoot at the line, I heard the gabble of cranes flying south. I looked up and found a pair of V’s moving across the sky toward Russia. While we remained stopped at a border, our bodies nailed like stakes to the ground, the cranes flew on, as unconcerned as clouds with other people’s nations far below.

Photo: European cranes passing over the Curonian Spit, Craig Childs

Am in love with this story! Such a treat to hear about the beloved Cranes. Thank you.

Thanks for these insights and realizations from around the planet. The call of the cranes is, to me, a primordial one, that invariably has me looking up! I too am grateful for the way they mark the seasons as they, along with vast numbers of ducks, geese and other migrants, bless the San Luis Valley with their presence each spring and fall. They are a vital part of our community, and a tremendous amount of collaborative conservation work has been and is being done, across private and public lands, to protect habitat, provide needed food resources, and to educate and help people enjoy and appreciate these iconic birds. And this essay is a worthwhile addition to that effort of appreciation. As Jacque Cousteau said, “People protect what they love.”