This post first appeared in September of 2019 and the mushrooms never stop coming.

Paul Kroeger is a wizard. Rolling his quick little cigarettes like skinny sticks of dynamite, he halts and flows like bearded water, crossing streets of East Vancouver at angles between the cars. He slips behind houses, not the path of his fellow human beings, but grassy patches behind offices and medical facilities.

In front of a first floor apartment window, Kroeger coos, “Oh, look, look, look!” A ring of damp brown mushrooms has sprung up around a pine tree, grown from its roots. “Ectomycorrhizal,” he says. The mushroom mycelia is symbiotic with tree roots, taking to specific kinds of trees, gathering nutrients and water for the tree at the circumference of its roots, thus the circle.

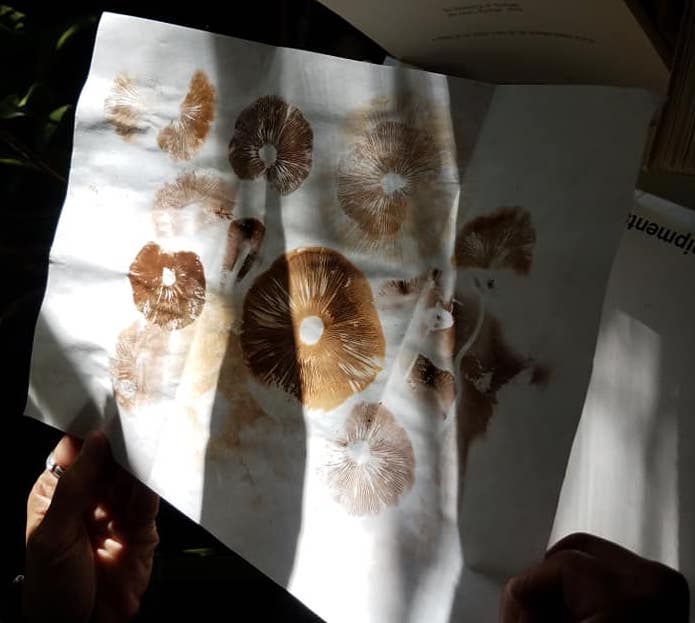

Kroeger — the oe in his name more like oo — has worked at University of British Columbia studying the biochemistry of medicinal mushrooms, and is co-founder of the Vancouver Mycological Society. At the end of a day hunting in the city, he empties his collected mushrooms at home to take spore prints, gill-shaped dustings left on paper overnight. Specimens that he doesn’t dry for science, he chucks into his yard, hoping their spores will take. He has a small house in an old-tree neighborhood, his yard a crowded grove, overgrown compared to the houses around him, odd mushrooms springing up all over.

The map that Kroeger reads of this city lies underground, filaments and roots sending him in zig zags. Crazy, you might think, if you saw his path through the day. I say obedient to a peculiar paradigm, a facet different than the rest of ours, the birds, the bushes, and the ridiculous scales of human architecture. Mushrooms come up in lanes of grass and weed between street and sidewalk.

A collection of mushrooms can be called stand, troop, or copse. It is hard to know what to call them. Genetically and evolutionarily closer to animals than plants, mushrooms and their underground networks are only recently gaining proper nomenclature. Until the last few decades, fungus was not recognized as a distinct kingdom, lumped in with plants as a subject of botany. Now it is mycology, representing one of the major kingdoms of life on Earth: flora, fauna, and funga.

The word funga appeared last year in the Journal of the International Mycological Association, which publishes formal proposals relating to the classification of fungi. The article, pitching the “Fauna, Flora & Funga Proposal,” reads, “As public policies and conservation requirements for biodiversity evolve there is a need for a term for the kingdom Fungi equivalent to Fauna and Flora.”

Giuliana Furci, a Chilean researcher, is one of a group of mycologists coining this term and an author on the paper. In her home country, Furci has been instrumental in including funga in environmental legislation, leading to the protection of 22 native fungal species. Along with plants and animals, environmental impact studies in Chile now include mushrooms.

Looking for funga at the other end of the hemisphere, we find drug needles and light trash in the underbrush. Families go by with strollers. Cars pull in and out. A man with a tool belt walks onto a construction site. Kroeger, bony, long-bearded field scientist, is on his knees with a knife, right in there with the rest of the carnival. His voice is more puzzling and kind than a rainbow. He stops just about anybody to point out what he finds: upthrusting red and white Amanita muscaria, rings of fruiting bodies like fairy kingdoms around the trunks of street trees. They came out with the rains all over the city, some as big as dinner plates, some like cherry-colored doorknobs dotted with white flakes. Kroeger crawls on the ground with his camera, capturing tableaus, tapping on their tops, feeling their firmness.

On the street, most of the people Kroeger talks to, because this is Canada, pause and have questions. Some, because this is the Pacific Northwest, pull out their phones to show us mushrooms. They tell Kroeger which ones are emerging on other blocks. Some tell us about the one we are looking for, sightings of the death cap, what brought me to Vancouver working on a piece for The Atlantic. The man with the construction belt has pictures of them taken a few blocks away. He knows the species, Amanita phalloides, shimmering greenish gold caps that look like beautiful seasickness. From the gills down, they are lily-white.

Organ failures, bleeding out orifices, death by the most horrible means. On average, one person a year has died in North America from ingesting a death cap. The number rises as the mushroom spreads: foreign, invasive, a European native gone worldwide. Sound familiar?

They are said to be quite tasty, and it could be a day or two before signs of illness set in, like an invisible bullet. Liver cells take up the poison where it inhibits enzyme production. Protein synthesis fails and the internal cascade begins.

Kroger finds them by rumor and by the look of streets, on a hilltop peering across the city or from a bus crossing an overpass. The way you might study a mountain slope or ridge, thinking of lightning, rain, and snowmelt, he uses architecture and the age and kinds of urban trees to find these mushrooms. Mature broadleafs, European ornamentals, hornbeams, lindens, oaks, mixed with what he calls mid-century modern domestic architecture, are where the death cap dwells, brought over in the roots of ornamental trees, European saplings cultivated at a nursery on Vancouver Island.

Boom, boom, boom. Death caps appeared in cities like bombs going off, New York, San Francisco, and now Vancouver. Waiting in ectomycorrhizal quiescence beneath the ground for 60 years, the caps don’t rise until trees reach maturity. The architecture is 60 years old, the trees mature, and Kroeger is on his knees with his sharp, curved knife, prying them up, keeping track of their advance like a bell-ringer, a sentry at the gate.

I follow Kroeger for days, on the bus, by foot, like pursuing a fox, not a creature of sidewalks. He has the keys to the underworld of the city. The only time I see his flow halt and rumple is between stops, finding our way through the downtown area. Concrete surrounds us as we ascend stairs to the clattering clomp of hundreds of other footsteps. I keep asking where the closest mushroom might be, and he says five minutes away, maybe ten. There are secret places in the city. Nervously hemmed in, he says that wherever they are, they are too far from here. When we reach grass, or just a patch of soil, he calms. He nudges rocks with the toe of his sneaker. He pours into lawns. His voice pearls at every find, hands wringing happily. He’s returned to the lairs of his beloved. While the rest of us pulse and commerce on our grids of industry, Kroeger spins on the axis of funga.

Photos by Daiva Chesonis and Craig Childs

I enjoyed this essay. The version in the Atlantic is also very good. It is nice to see a photo of Paul Kroeger. He does indeed look like a wizard or “doctor”.

I met Craig Childs once a few years ago in my hometown in Utah. He has a presence. I didnt know it was him until the next day when i went to a lecture about cultural property. He wrote a whole book about this and was here to talk about it. Aha! That nice interesting man i met at work is famous in our small circles!

Ive read several of his books but my favorite is “House of Rain”.