The other day, my friend Max — a brilliant aquatic scientist whose work lies at the center of the herpetology/gender studies Venn diagram — tweeted a comment he’d received from an anonymous peer reviewer. Evidently this reviewer had doubted Max’s claim that frogs have political economic histories. Max’s reply: “lolz yes. All critters on Earth have socio-cultural & political economic histories.” (If the reviewer found this tweet convincing, Max didn’t say so.)

I agree with Max’s assertion — heck, even a creature as obscure and humble as the achoque salamander is deeply embedded in socio-cultural webs of religion, science, and regulatory bureaucracy. That said, I’m skeptical that every species has an equally compelling socio-political history. While one could theoretically write an exhaustive work of political economy about, I don’t know, the red-backed vole, I’m not sure I’d want to read it. (Apologies to all the mammalogists I just mortally offended.)

I’m biased, but I’d argue that the political economy with the most explanatory power in the non-human animal kingdom is that of Castor canadensis, the mighty beaver. How many other species were the subject of a transcontinental trade that spanned centuries and fundamentally restructured European and Indigenous North American cultures? How many species spurred the colonization of a continent, started wars, inspired a real estate transaction as grandiose as the Louisiana Purchase? How many species were so economically important that regional currencies were pegged to the value of its fur? I could go on. Somebody should really write a book about this.

Anyway, Max’s tweet got me wondering: Which other species are crying out for a popular political economic history? Most of the obvious ones, I think, have been written. Mark Kurlansky covered cod (and, in so doing, made the single-species biography a genre). David Montgomery did salmon. Whales have been comprehensively documented, most recently by Rebecca Giggs and Bathsheba Demuth. There’s no shortage of books about influential disease vectors (mosquitos, rats, ticks) and species at the center of management controversies (wolves, bears, spotted owls) and commercially valuable sea creatures (save some fish for the rest of us, Paul Greenberg).

In short, it’s a crowded market. (Although I do think the world badly needs a prairie dog opus.)

(As a brief aside, I’m aware that I’m defining political economy vis-a-vis species’ interactions with humans, a narrow frame that reveals my anthropocentrism and limited imagination. No doubt many animal societies have endlessly rich political economies of their own, entirely unrelated to their relationship to humans. Imagine the palace intrigue within, say, a naked mole rat colony.)

All of the above notwithstanding, there’s one deserving critter whose political economy has never, to my knowledge, been thoroughly explicated: the Colorado potato beetle.

***

I first became acquainted with Colorado potato beetles this summer, at a friend’s house here in Spokane. (Credit to Carl for identifying them; the fact that I didn’t know them by sight betrays me as an inept gardener.) They struck me as charmingly goofy: broad-shelled and ungainly, gaudily striped in green and white, bumping fecklessly around a back porch light. I could hear the humming brrrrr of their wing-cases as they helicoptered merrily through the warm dark.

The next day I googled my new friends. Colorado potato beetles, I learned, had a stranger, more convoluted history than I could’ve imagined. Here’s the brief version. Nobody’s quite certain, but the Colorado potato beetle — aka the ten-lined potato beetle and, delightfully, the ten-striped spearman — likely originated somewhere between Colorado and northern Mexico. Within its native range, the beetle’s preferred food was a tough, prickly nightshade called buffalo bur. In 1859, though, they were discovered chowing down in a potato patch outside of Omaha, and they never looked back. (To be fair, I’d rather eat French fries than buffalo bur, too.)

The 19th century was a good time to be a spud-lover. White colonists were planting potatoes willy-nilly, and the whole continent must have seemed like a buffet. The beetles hopped from field to field, seizing around 85 miles of new territory per year, expanding their range both east and north. (Some sources describe them as “reverse pioneers.”) They were spectacularly voracious — a single adult can eat 1.5 square inches of potato leaves daily — and almost unfathomably abundant. Entomologists described the beetle’s takeover as the “advance of a great army.” Trains derailed wherever the crunchy multitudes crawled across tracks.

Across the Atlantic, Europe watched the beetle’s progress with horror. The Irish potato famine had shown just how much suffering a tuber shortage could inflict; the last thing anyone needed was another plague. In the British House of Lords, one Lord Stanley of Alderley asked “whether it might not be the safer course to prohibit the importation of all American potatoes except those which, being intended for seed, were carefully packed and sent clean and free from the beetles or their eggs.” In 1875, a number of European countries prohibited American tater imports altogether.

Over time, the beetle came to be associated with American military power. During World War II, Germany, terrified that the Allies would smuggle in potato beetles to destroy their food supplies, established the Kartoffelkäferabwehrdienst, the Potato Beetle Defense Service. Germany also considered deploying the beetles themselves, and bred millions with the intent of carpet-bombing Britain’s own potato fields. To figure out how many beetles they might need to air-drop, the Third Reich apparently dumped beetles on itself; in one trial, scientists released 14,000 beetles and recovered only 57. “It appears no one considered the prospect that Germany might be subjecting herself to a (biological warfare) attack during such aerial releases,” observed one Benjamin C. Garrett.

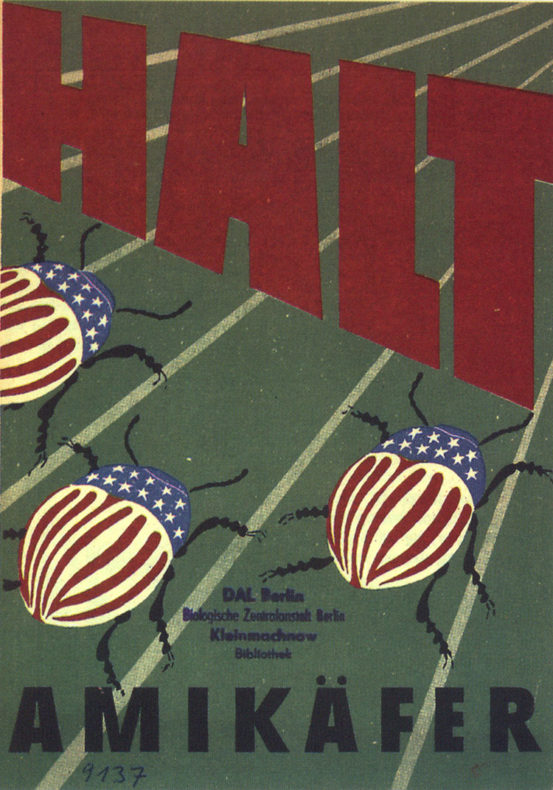

Although the beetles were never truly weaponized, they thoroughly infiltrated Europe in the war’s aftermath, causing devastation wherever they spread. (In Hungary, their arrival was so catastrophic that it’s commemorated today with a Stalin-esque statue.) The Soviet Union cast the Amikafer — Yankee beetles — as a convenient instrument of Cold War propaganda, churning out leaflets, articles, and posters that depicted them in little boots and helmets. Rumors flew that Americans were dropping beetles onto East Germany, and schoolchildren were dispatched to pick them by hand out of the fields. (They’re notoriously resistant to pesticides.) “We would go down the rows of potatoes and everyone would try to pick up as many beetles as they could, maybe 20 or 25 in a day,” one resident recalled to the BBC. “And then we would put them in pots or little glass jars and they would be taken away and destroyed.”

The rumor was, as far as anyone knows, false. Still, the legend endured. The insect became an enduring symbol of American depravity, as horrific in its own way as the atomic bomb. A beetle is never just a beetle.

Anyway, there’s surely a lot more to say about the Colorado potato beetle, but maybe we should save it for another format. Clearly, what the world needs most in this particular moment is an exhaustive, ocean-spanning book about the social and economic history of the Colorado potato beetle, an insect whose biography is far stranger than I could ever have imagined. (You can have this idea for free, environmental history graduate students.) I’m certain the requisite primary sources exist: The Amazon description of one book, published in 1907, suggests that domestic ducks readily eat potato beetles, but that chickens disdain its “nauseous taste.” Who knows what other gems the book itself holds? I know what I’m asking for this Hanukkah.

To the good readers of LWON: What other Colorado potato beetle facts do you have in your pocket, and what other non-human political economic histories would you want to read? Looking forward to the comments. And thanks again to Max’s provocative tweet for inspiring this post.

Photo: Scott Bauer, USDA/Wikimedia Commons

Poster: potatobeetle.org

Henry Hobhouse writes about political economy in “Seeds of Change: Five plants that transformed mankind” for quinine, sugar, tea, cotton, and the potato. The Colorado potato beetle gets only a brief mention so there’s room for much more.

Hi Peter, thanks for the rec — will take a peek at Hobhouse’s book!