If you study the breeding habits of a stout gray seabird called the rhinoceros auklet on a couple of islands in Washington, a field season typically lasts from May until August. Come fall, then, you have a choice: you can either dive into the data and analysis and statistical whatnot, or you can spend some quality time with the photos you took during the field season, and so try to make it last a little longer.

I usually opt for the photos. I say this even though I’m not a very good photographer. My portfolio consists mostly of run-of-the-mill landscapes and seascapes. Often those -scapes are filled with dots. (“Are those supposed to be birds?” my daughter asks.) No matter. I just like to look at the auklet’s islands. One, Protection Island, is about two miles off the north coast of the Olympic Peninsula, in the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Here are a few of the several hundred shots I have snapped of it over the years.

Protection is roughly 400 acres in size and in the summer hosts more than 70,000 auklets, making it one of the species’ five or six largest colonies. Although a couple of towns are visible over on the mainland, to be on the island is to feel a satisfying sense of remove. In the evening when the light is just right, with the sun setting and the Olympic mountains to the south, you could be walking through an Andrew Wyeth painting. It’s so beautiful that even I can make it look half-decent.

One thing I don’t have many photos of is the auklets themselves. Blame their life history. When we visit the island the chicks are hunkered in burrows that might be more than nine feet deep. The adults are at sea, meanwhile, hunting for small fish. They return to the colony to feed their chicks only at night, and then they leave at dawn. We check on the chicks during the day using infrared cameras. These we snake into the burrows on long cables, interpreting as best we can the grayscale images sent to our visors at bizarre angles. Making sense of those images can feel more like art than science.

I should say that I don’t have many photos of living auklets. If you study the breeding habits of rhinoceros auklets on a couple of islands in Washington, you soon become familiar with the signs and signifiers of their deaths. When we are walking about the island, for instance, we might come upon an auklet’s severed head, or a pair of body-less wings, or, most often, a bunch of gray feathers strewn among the grasses—all that is left of an auklet after it has been consumed by a bald eagle. These leavings don’t make for great pictures, but we get a good laugh nonetheless. “Aha, looks like an explosive molt!” we will chuckle over such feather piles.

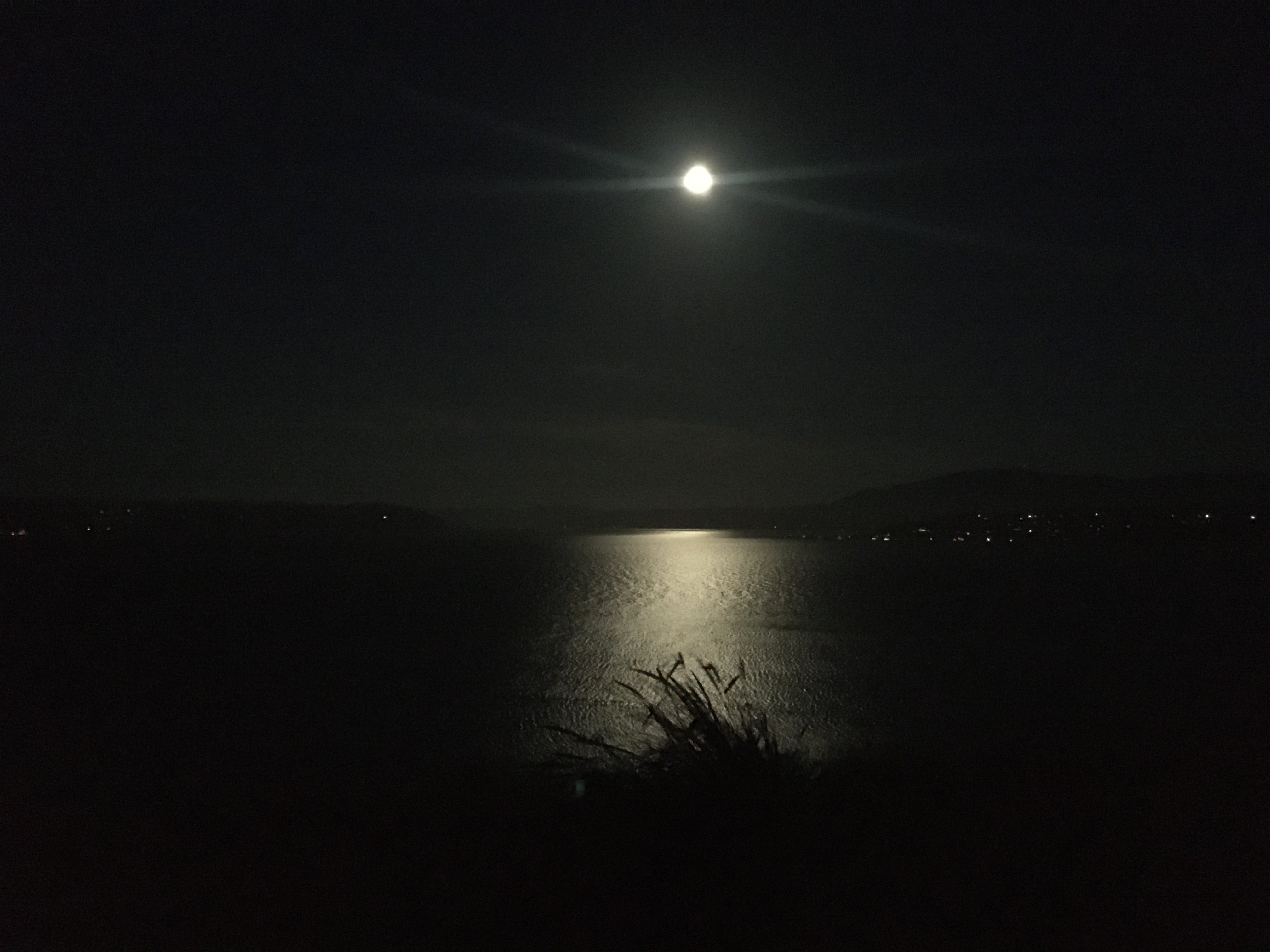

I hope we (I) can be forgiven a certain ghoulishness when it comes to dead auklets. I don’t mean to sound glib. Eagles are why auklets only dare come to the island under cover of darkness; and I have an idea of what it is like to be hunted. Eagles may be famous for their sharp eyes, capable of seeing a deer mouse a mile away or whatever, but their predatory precision at night can leave something to be desired. Apparently my old ragg wool hat approximates an auklet, I have learned, because more than once I have been out under the light of the moon when suddenly I feel something coming, and I turn just in time to see an eagle bearing down on me, eyes fixed, legs lowered, talons splayed. I yelp and hurl myself to the ground, the eagle sweeping so low over my head that I can feel its wingbeats. Having missed, it lands among the tussocks and turns to try again, at which point I leap up and wave my arms and yell and holler and in general try to make it as clear as I possibly can that I am not an auklet. Then the eagle flaps balefully off. If I were an auklet, I think to myself, I would be dead.

Death and its agents are never far from a breeding colony, but that is part of the appeal of field research: not only to study your subject, but also to see how it fits into the larger world, within a cast of mighty characters. One morning a few of us were leaving Protection on our way to another island that hosts a small colony of tufted puffins. The boat had just puttered into the strait when Chad, who was driving, pointed out the window. “Orcas!” he shouted. He cut the motors and we all dashed to the bow. In the distance, six or seven black dorsal fins bladed through the water. I whipped out my phone and started snapping away.

In Washington, the orcas best known and loved are the southern residents, an endangered group that frequents the San Juan Islands during the summer. Or used to frequent them. The southern residents feed mostly on salmon, and as salmon populations have declined, the southern residents show up less and less. In their absence another type of orca has increased: the transients. Unlike the southern residents, transients hunt marine mammals.

People who study orcas around here know them so well that they can tell the types apart at a glance, but we could only marvel at their generic orca-ness. Some were within fifty yards of us, and every so often one would punctuate the air with a heavy pfwoof! of breath. One—a big male—was even swimming straight for us. This is going to make an amazing lock screen, I thought, shuttering madly.

It was then that the harbor seal popped up between us and the orca. It looked over at us and back at the big male, and we knew then what kind of orcas these were. The seal dove but came up again within a few seconds. I don’t know if it was injured or exhausted—probably both—but this time it stayed at the surface, gazing at the big male’s dorsal fin. Just watching and waiting.

I let my phone fall from my face. I think my jaw hung slack. The big male swam to the seal slowly, almost languidly. As the two converged in time and space, I had the presence of mind to lift my phone and take a picture the moment they met and the seal’s head snapped back from the force of the fatal bite. Then the big male smoothly dove with the seal in his jaws, and water closed over the pair like nothing had happened.

All of which brings me to why I will never be a good photographer.

- At its barest a photograph is a frozen moment. Or maybe captured is a better metaphor, given the circumstances. A good wildlife photographer can capture the best, most resonant moment: the moment that should live forever. But gifted with a chance to see what I consider one of ecology’s most essential relationships, the moment I captured was merely the most lurid: the moment a predator took its prey’s life. I didn’t have the subtlety or skill—the art—to capture the eternity that had come before, when the seal knew it was about to die and could do nothing but turn and watch.

- I don’t fill the frame.

I don’t remember exactly what we said afterward—some mix of Huh and Woah and That’s not something you see every day. We watched the orcas for a couple of minutes more, but the air of joyous natural history spectacle was gone. Eventually we trooped back into the cabin and Chad started up the motors. The orcas were moving on, and we, too, had other places to be.

Photos by the author

Beautiful

Thanks, Eric. Sometimes I think we’re blessed by not being so good at some things so that we can be good at other things. I love these stories of field research: the humor and slight terror of being mistaken for an auklet, the deadly dance of seal and orca, the explosion of feathers not yet blown off by the wind. Grateful to you for sharing these moments of awareness.

Thanks, Irene and Rachel. Yes, field research is good at providing me with regular reminders of things I am not good at!