New York City was my forbidden fruit. It didn’t go with my identity as a nature writer, so I kept quiet about these urban forays. Wilderness trips I’d time so I’d get into the thick of humanity as swiftly as possible. After two weeks backpacking in the west end of the Grand Canyon, not using trails but roping and scrambling through shadowy gorges, I flew out of Las Vegas. That night, I was on the street in Manhattan.

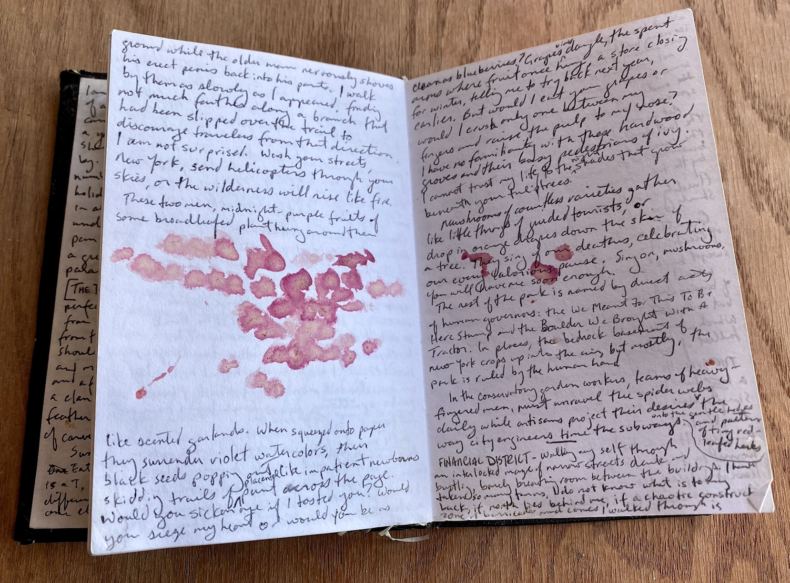

With as little transition as possible, my eye felt sharpened, my skin prickled, and my nose lifted to passing scents: bakeries, car exhaust, gutter urine, and buckets of flowers on street corners. The city was a landscape. People I saw as rivers. Buildings were canyon walls. I dipped in and out of flows, walking streets and riding subways for ten to fifteen hours a day. In the early morning hours, I made it back to a third-floor room and small bed on the quiet glen of Jane Street in the West Village. My journal, rain dimpled and smeared from the field, dotted with the color of berries picked in Central Park, became a repository of urban observations:

Cigarettes mouthed as if they were hot cables of electricity, swept to the corner of the mouth, swept back down. Hated. Loved. Hated.

When I try to leave the Financial District, the city of barricades closes on me. I am walking in circles, but only in straight lines. Where is the sun? Which way do the shadows lean against the tallest of buildings? I cannot see.

On a prismatic September morning, the air rarified from here to outer space, I was on my way to a meeting in lower Manhattan. Emergency vehicles raced down Fifth Avenue and people rising out of a subway station ahead of me stopped stock still, all of them looking up.

You know the rest, you’ve seen it played over and over. People thought it was a movie only to learn it was real.

A woman covered her face with her hands and cried out that her sister worked up there. I pulled my journal and wrote down her words. It was all I could think to do. Reams of smoldering paper blew overhead; I wrote that they looked like birds on fire because that’s what they looked like.

When I called my editor at National Public Radio later that morning, getting through on a landline from Jane Street, she said, “You’re where?” She said she was patching me into the live national feed where host Neal Conan picked me up.

NPR Transcript:

CONAN: Can you describe what you saw?

CHILDS: Well, I can give a visual and emotional sense of what it was like there because I arrived just moments after the plane struck the towers from about a mile or so away. I came around the corner and could see flames just crawling up the sides of the buildings and a robe of gray smoke heading off to the southeast. And people standing around at that moment were just voiceless. People were coming out of the subway onto the street and just standing there transfixed, staring at this thing. People every once in a while would point and shout and say that there were people jumping out of the towers. But, of course, from where we were, you really couldn’t tell. You know, a person that high up is indistinguishable from a falling desk or a file cabinet. And that’s when people started looking around at the buildings above us, and I heard a sigh rise up, just thousands of people gasping at once. And I looked up and saw that the south tower was collapsing. And I don’t even know if the word collapse is correct here. It just disappeared. The lines that defined the building dissolved, and the building just vanished.

What really struck me is that when the south tower came down, just so many hands went up in the air and it looked as if people were trying to stop it, they were trying to reach up and grab the building. Just thousands of hands just shooting up into the air all around me.

It would be days before I started writing again. I was too shaken from that morning. Over the next several days, barricaded into lower Manhattan below Fourteenth Street, I slowly began to record names of faces belonging to innumerable missing people going up on fliers. Buildings and lampposts became canvases of hundreds upon hundreds of thumb-tacked and taped pages. Have you seen my husband, my daughter, my brother, my wife?

From my journal:

In a bloodline across the street, the blue awning of a white building, two flag poles, one of the United States, one of St. Vincent’s hospital. While at our backs the street fills with gurneys. The ambulances return empty, not even the smoke darkened faces of firefighters coughing up blood from burning metal. The ambulances come back like empty sacks that we all turn to watch, hopefully, looking over our shoulders to watch the unbundling, doors opened, no one inside. No survivors. Then we look back to our line, ready to name our blood types as if enlisting ourselves…

I walk away. My name is on a list.

Another line. I stand. Get to the front. I tell them the same. I’ll go down there. I have hands. I will dig with my fingers. The sweetness of the woman’s smile, the sting of her bitter compassion, as she knows the same thing I do. There are no survivors.

Shrines grew outside of each fire station. Strangers kept candles lit. One evening, I crouched with stubs of matches, relighting one wick after another. Streetwise breezes bent the flames and blew a few out. I started again. It was better than sitting in my room staring at a wall, waiting for calls that never came. After a while, a woman put her hand on my shoulder. I looked into the eyes of someone I didn’t know. We said nothing out loud to each other. I stood and she crouched, taking over lightning the candles.

A few days later I went into a studio to record a piece for NPR, talking about hundreds of people joining along the Henry Hudson Parkway to applaud as rescue vehicles drove to and from Ground Zero. The piece was edited, its words not as raw and suddenly uttered as those on the first day. Three public radio stations had crammed into one studio because their tower had gone down. People passed wires over and under each other. The top of a filing cabinet had been turned into a desk. I watched from a soundproof booth, story gripped in my hands as I waited for an engineer to say go.

It wasn’t September 11th alone. It was the twelfth, thirteenth, and fourteenth. Those days did not end. They kept feeding each other. I swore I’d go back every September, and for four or five years I did. Then, without noticing, I stopped. Like a river flowing around a boulder, the city healed itself and that sweet autumn in 2001 fell into line with all the rest.

NPR Transcript, September 11, 2001:

Childs: I guess what I’m seeing now is that the city has been turned from a machine into something organic. It’s just filled with emotion, not necessarily the panic that you might imagine; just sheer emotion everywhere.

Hi Craig,

When September 11 comes around I think of you, Jane St. and me so much wanting to be there .

Oh, Elizabeth, I’m glad at least I could be there in your stead. Thank you for opening Jane St. to me. I will always have that place in my heart, no better base for exploring that boggling city.

Thanks for sharing your account Craig. Crazy you were there. I Dunno if I ever told you, my uncle Jeff Coombs was in Flight 11 when it hit the towers. That event launched my interest in the inner workings of international power structures..or as much as I’m allowed to see…and the truth behind 9/11. To this day I can’t have an honest conversation with my aunt, Jeff’s wife, about my beliefs surrounding the events of 9/11. In fact, where we were once very close, regretably we have now drifted apart.

Jay, I had no idea, I’m sorry to hear about your uncle. So many lives and ends of lives were tangled up in that day.

This is a very powerful read and I am not surprised you happened to be a witness to this tragedy. And Jay, wow… I am one of those few who didn’t see images of the planes/towers etc for a couple days, maybe even a week. Crazy huh? I didn’t have a TV. That morning I was driving to my job as a pre-school teacher, outside Durango, enjoying the peaceful morning drive. As I was engaging the children, we all (teachers) learned of what happened. I suddenly felt like an island, with humanity “out there”, while I was immersed in the “innocence” of children enjoying their playful moments of life…

hi Craig. 2 friends and I were in the NE Sawatch at Mystic island lake when it all went down. We emerged to drive through Eagle CO where all the flags were at half-staff. My first thought was GWB had been assassinated??? We learned later, when dropping off one of my amigos, what had actually happened. That same friend died last year in an avalanche in the San Juans while skiing out of a hut that I had recently visited to celebrate another friend’s 70th birthday. The memories cascade and intertwine in vines of a twisted reality looking for the best light. Que loco! Thanks for the re-post. Abrazos amigo, Ryland

Thank you, Craig. I had forgotten your words but have not forgotten how your voice made me feel that day. Love you.