Deep Note, which made its debut on May 25th, 1983, at the premiere of Return of the Jedi, is a 30-second tour de force of electronic music. It would play in those few minutes of darkness before the featured movie began, just after the adverts for oversized and overpriced sodas and containers of popcorn.

Here’s me on Deep Note: Eyes closed. Shallow breath. Relaxed to the point of feeling bodiless. A Buddha smile as Deep Note’s first sonic hints buffet those tiny bundles of sound-sensitive hair cells in my cochleas. Then, as the Deep Note algorithm orchestrates the build, climax, and resolution into the final chord, I go full-in with that sequence. My skin toggles from its boundary-from-the-universe setting to a connected-to-everything setting. Vastness, this is, as Yoda might say. Thirty seconds. Trippy deep. Then, just like that, it’s movie time. I do not know if others in the theater shared my transient freefall into vastness, but I hope at least some of them did.

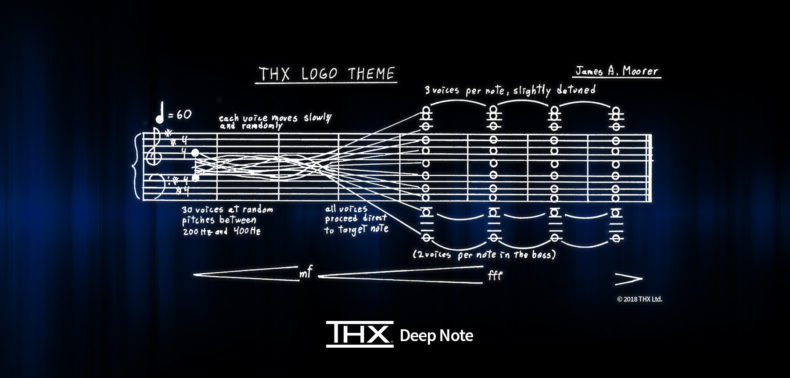

Deep Note, which served as an audio logo for THX, a company that director George Lucas established to develop technologies for upgrading the experience of moviegoers, originally consisted of 30 electronic tones, or voices, spanning over ten octaves. These evolve from an initially dim and menacing din into a chord of such shimmering coherence, grandeur, and expansiveness that for me it is nothing short of epiphanic every time I hear it. Here is how I know I am not exaggerating: Deep Note made it into the script of the Simpsons episode that aired on April 14, 1994, in which the head of an animated moviegoer listening to Deep Note explodes. One of these days, I would like to treat Dr. James ‘Andy’ Moorer, the sound engineer and artist who created Deep Note, to an epic thank-you dinner.

After the 1983 premier of Deep Note, whenever I would go to a movie at a theater that had been audio-equipped and certified by THX, I knew I would experience a transporting moment of vastness when Moorer’s Deep Note would crescendo out of the theater’s speakers. For me, the sound was always so expansive and uplifting that I would find myself grasping the armrests and closing my eyes so as not to squander one instant of vastness from the waveform emanating like magma from the theater’s sound system. Just as you lose the pleasure of chocolate if you multitask while reading a book or even listening to music, you can lose Deep Note’s moment of vastness if you hear it without devoting your full listening attention to it. To listen to Deep Note while crunching on popcorn is like reading an ad for hemorrhoid medicine while standing in front the Mona Lisa at the Louvre. I have never done either of those things.

In an interview on the podcast Twenty-Thousand Hertz, which features the sounds in our lives, Moorer revealed that among his inspirations for Deep Note were two of my own all-time favorite pieces of music. I listened to these over and over in my younger years when I used to haul from dorm room to group house to apartment a set of milk carts filled with vinyl records and a pair of enormous Cerwin Vega speakers.

On one of those albums, the Beatles’ St. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, at about the midpoint and toward the end the song A Day in the Life, are orchestral musical buildups that seem like they might not end. That was one of Moorer’s inspirations for Deep Note. And so was Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in E Minor. This piece is my favorite one on another album—Bach Organ Favorites played by E. Power Biggs—that was in that long-gone vinyl collection of mine. In addition to having an impossibly apropos name for a musician who played the world’s most magnificent pipe organs, Biggs had a set of the biggest hands I had ever seen. On the album cover, he sits at a gorgeous pipe organ, his giant paws resting on his lap. “Bach’s fugue, after noodling around a little, builds this huge chord that resolves in just this massive massive chord,” Moorer says. Here, Moorer sounds like me describing Deep Note!

These two already vast musical moments were merely the points of departure for Moorer. To achieve Deep Note, he built on these inspirations with a combination of what in 1983 was leading-edge electronic audio technology along with some arcane and psycho-acoustically fantastic musical choices. Summoning his Stanford training as an electric engineer, he designed and built his own “digital signal processor,” a DSP. That’s a specialized computer for arithmetic calculations associated with digital audio data. He also wrote out 200,000 or so lines of computer code to operate his one-off DSP. All of that took about two years.

But it might have been two nuances that only deeply learned musicians would even know to try that made Deep Note so powerful for me and that exploded the head of that Simpsons character. One of these was Moorer’s choice to swap out the usual “equal temperament” tuning of the chromatic scale of musical tones for a 2500-year-old tonal framework known as “Pythagorean tuning.” The other pivotal nuance Moorer embraced has to do with the 30 oscillators, aka notes, aka voices, which his algorithm randomly assigned at first within a specified range of frequencies. These voices fluctuate (that menacing din I described earlier) at first. Then each voice makes its way toward one of eleven target notes that span over a range wider than a piano’s. But wait, there’s more. Moorer assigned two or three oscillators to each target note along with this sonic twist: rather than assuring these sets of voices would sing out in perfect unison when they reached their respective target notes, Moorer made sure that the several oscillators assigned to each end note would be slightly de-tuned when they reached the destination frequency. This detuning detail, Moorer said, “is what makes the final chord shimmer.” For me all of this innovation harmonizes into an audio metaphor for the great expansion of the universe after the Big Bang in which all points of the universe race away from each other and yet collectively yield a cosmos of utmost beauty and power.

Though no longer a routine feature of movies, Deep Note still is, in its various renditions (some with up to 90 voices), a rapturous sonic experience best absorbed when wholly relaxed with eyes closed, at high volume, and pumping through a kick-ass sound system. I miss my Cerwin Vegas. With willing abandon, this chord can transport you parsecs beyond the smallness of the actual space you occupy and the few seconds it takes to hear Deep Note. So finally, here it is: Deep Note can envelop you within an uplifting vastness conjured by sound crafted by math, electronic and audio engineering, and artistic sensibility to engage the evolutionary gift of our ears and brains in a way that provides momentary transcendence from our exquisite finitude.

_____________

Ivan Amato is a writer, podcaster, science-cafe facilitator, and crystal photomicrographer in Hyattsville, MD. Currently he also is working on a book of essays about a diversity of vastnesses in his life.

THX, the THX Logo, and the THX Deep Note audio mark are the property of THX Ltd., registered in the U.S. and other countries.

Marvelous post. Thank you!