Manhattan rattles my ears. Subway lines shake the fine bones inside my head. Cars honking on the street change the way my brain physically functions. When I stayed in the city a week ago I noticed the same as I always do: noise.

I live in a quiet place off the grid in Western Colorado and when I plunge into urban melee it is a primarily aural experience. Much of the city runs at about 85 decibels, a level that takes just eight continuous hours to permanently kink the hairs transmitting sound through the inner ear. The average subway ride comes to around 112 dB, somewhere between a shouted conversation and a power saw going off near your head.

An audiology researcher in Berkeley, California, informally tested the sound of his local transit system and found sustained peaks at the level of a rock concert (around 120 dB). On top of that, he noted, many passengers were wearing ear buds, listening to music loud enough to mask the external noise, far exceeding limits on volume and time-exposure that lead to permanent damage and hearing loss.

I’ve made a habit of seeking out the quieter places in the city, this time taking shelter in a poetry reading room. At other times I’ve gone to Wall Street at dawn on a Sunday morning for its towering quiet or, once, the Ramble in Central Park at night, also quiet but disturbingly dangerous.

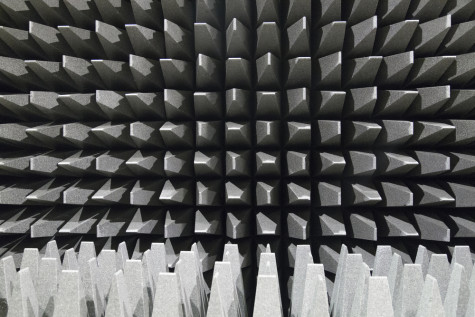

Every city has its sanctuaries from noise. The most profound I ever encountered was an anechoic chamber in a basement on campus at the University of California, Berkeley. This soundless chamber sits on the bottom floor of the Hafter Hearing Center, overseen by retired audiologist Erv Hafter, who took me inside. Hafter carefully explained that an anechoic chamber is not an infinitely silent place. As far as he knows no such thing exists on Earth. He said there are movements in the ground, vibrations, jackhammers, even distant earthquakes.

As we stood in the master bedroom-sized chamber, I asked if I should be able to hear anything, and he said no.

“Sound may enter your ears, but you’re not hearing it,” Hafter said.

“It’s not reaching the brain?” I asked.

“Yes, it reaches the brain, but the brain is a filter. One of perception’s most important functions is to forget.”

In other words, silence, like noise, is what your brain allows you to consciously experience. The rest you decode and dismiss.

Covered top to bottom and side to side with foam-core filters, the space absorbed all noise but what was aimed directly at me, in this case Hafter’s voice. I could not stop staring at his mouth as he talked. It was as if he were speaking down a tube. I could hear his spit. Between words came a brief and eerie deadness, the room absorbing every sound. There was not a single detectable reverberation.

Hafter went to the large airlock door. “I’ll just shut you in. Take as much time as you need.” He drew closed the door, and I stood in silence, listening for earthquakes in China.

Used for sound experiments, the chamber is lined with speakers and trunks of electrical cables. The floor is a springy net of wire suspended over geometric baffles. The wires strained, sounding like violin strings under my feet as I slowly paced the room’s perimeter. I could not hear where I was, my ears fighting with my other senses. My eyes said I was in a closed space, but my ears said I was floating in an infinite void. Usually a person hears an entire auditory environment by detecting waves bouncing this way and that. In the chamber there was no context; it’s a sensory black hole.

An audiologist doing sound research with babies once told me anechoic chambers always made them cry. He said, “You have a perfectly quiet, normal 10-month-old, happy as a lark, maybe even half asleep; you bring them into an anechoic chamber, and they go berserk.”

I pulled the chains on four light bulbs, plunging the room into total darkness. It felt as if my senses were suddenly cut off, a sensation that would have driven a 10-month-old stark raving mad. We need sound as much as we need silence, maybe even more.

With vision removed from the equation, I focused on what I could hear, which at first was nothing. Muscle tension eased off my tympanic membrane, and the tiny bones in my ears relaxed, their tendons letting the hammer down. I began to hear the soft thrum of my heart. Then came a fainter noise, a hiss. It was not as sharp as the ringing in the ears known as tinnitus (the result of damaged hearing where auditory neurons fire off randomly because they are not being stimulated). I thought it was an air duct, but no air comes or goes from an anechoic chamber. I tilted my head one way and the other, trying to fix on the sound’s singular location, and realized it was in my head. It was, I believe, the sound of blood flow echoing through my skull, like sand pouring across velvet.

I lasted 45 minutes, then pulled the chain on each light, popped open the heavy door and emerged. I took an elevator up, pushed through the outside doors and stepped onto campus as if coming up for air. It was like getting my senses back, the relief of jet-noise and thousands of bustling students.

Last week in Manhattan, I found no anechoic chamber. I drifted through rivers of noise. The quietest it got on the street was a steady rain one night. Rain comes in around 50 dB. I could appreciate this sound because it wasn’t the human cacophony. Rain on sidewalks and the bluster of wind between buildings masked the maddening noise going on the rest of the time. At least then I could shut my eyes under this hiss on my umbrella and relax.

Images: Shutterstock

From Edgar Allan Poe; Silence – A Fable

“Then I grew angry and cursed, with the curse of silence, the river, and the lilies, and the wind, and the forest, and the heaven, and the thunder, and the sighs of the water-lilies. And they became accursed, and were still. And the moon ceased to totter up its pathway to heaven –and the thunder died away –and the lightning did not flash –and the clouds hung motionless –and the waters sunk to their level and remained –and the trees ceased to rock –and the water-lilies sighed no more –and the murmur was heard no longer from among them, nor any shadow of sound throughout the vast illimitable desert. And I looked upon the characters of the rock, and they were changed; –and the characters were SILENCE.

“And mine eyes fell upon the countenance of the man, and his countenance was wan with terror. And, hurriedly, he raised his head from his hand, and stood forth upon the rock and listened. But there was no voice throughout the vast illimitable desert, and the characters upon the rock were SILENCE. And the man shuddered, and turned his face away, and fled afar off, in haste, so that I beheld him no more.”

So good to find someone else who’s witnessed the Wall Street dawn–not just the quiet, but the blue in the streets while the sun is glancing golden off the tops of the skyscrapers, like a canyon in the mountains.

Ah, someone else whose overwhelming impression of NYC is the amazing noise. I wear earplugs when I fly. In NYC, I keep them in until I get into the hotel room.

I’ve been told that hiss is actually the current through your nervous system.

I do remember Wall Street on a Sunday morning, a quiet urban canyon. We are such sensory creatures and the senses help protect us. If I am walking alone on a quiet street, you can bet my auditory sense is on high alert. Or in a quiet woods for that matter.

Your words are always such a gift.

I was due to fly out of Dulles at 5 AM back in May, after a few days in Virginia. I had a cold at the time, with a nagging cough. At 1:00 AM, I realized I was better off just pulling an all-nighter, so I loaded up and drove down into DC. It was quite an experience prowling around all the monuments in the wee hours, the city dark and silent, the only people about a handful of Secret Service agents guarding various locations. It was like having the city to myself. I don’t know if I could handle it in daylight, in the heat and crowds.

Noise from and by shouting i find most annoying…noise from music can never be noise but can be simply sound, can’t be that irritating ..

Surprisingly, there are pockets of quiet in Manhattan, some in the most unlikely places. I lived on West 44th Street a couple of blocks from Times Square. The street front of my apartment was loud but the back was very, very quiet. I’d hear the clip clop of horses, train whistles and the occasional ship’s blast. All embedded in a relative ambient silence. One New Years Eve we went to be early. At midnight we awoke to a deep rumble. Not loud, really. More like a coming thunderstorm. Turned out what we heard was the roar of 500,000 people cheering the new year.

Great post. The first half and mentions of subway decibels reminded me of this recent post on OpenCulture: https://www.openculture.com/2021/08/the-sound-of-subways-around-the-world.html