Maybe it says something that one of my first crushes was on Slim Goodbody, a character who appeared on public television walking around with his insides out. He wore a bodysuit painted with images of tissues and organs and sang songs about respiration. There was something about all this that was irresistible—I mean, I thought he was cute, but the living anatomy was part of it, too, because he looked like something I shouldn’t be looking at, except there he was.

I’ve always felt torn about the inner workings of the body. I thought I wanted to be a doctor for years (sometimes I still search things like, “am I too old for medical school?”), and I also passed out while getting a blood test to volunteer at the hospital. One of my favorite books as a kid was called Blood and Guts. Another time, I fainted when the school nurse held up a set of empty blood bags while talking about a blood drive. When the midwife asked if I wanted to see the placenta after my youngest son was born, I was fascinated. It looked like an incredible tree with branching blood vessels. It looked like meat. It was strong and fragile and beautiful and all of a sudden I needed to lie down even though I already was in bed.

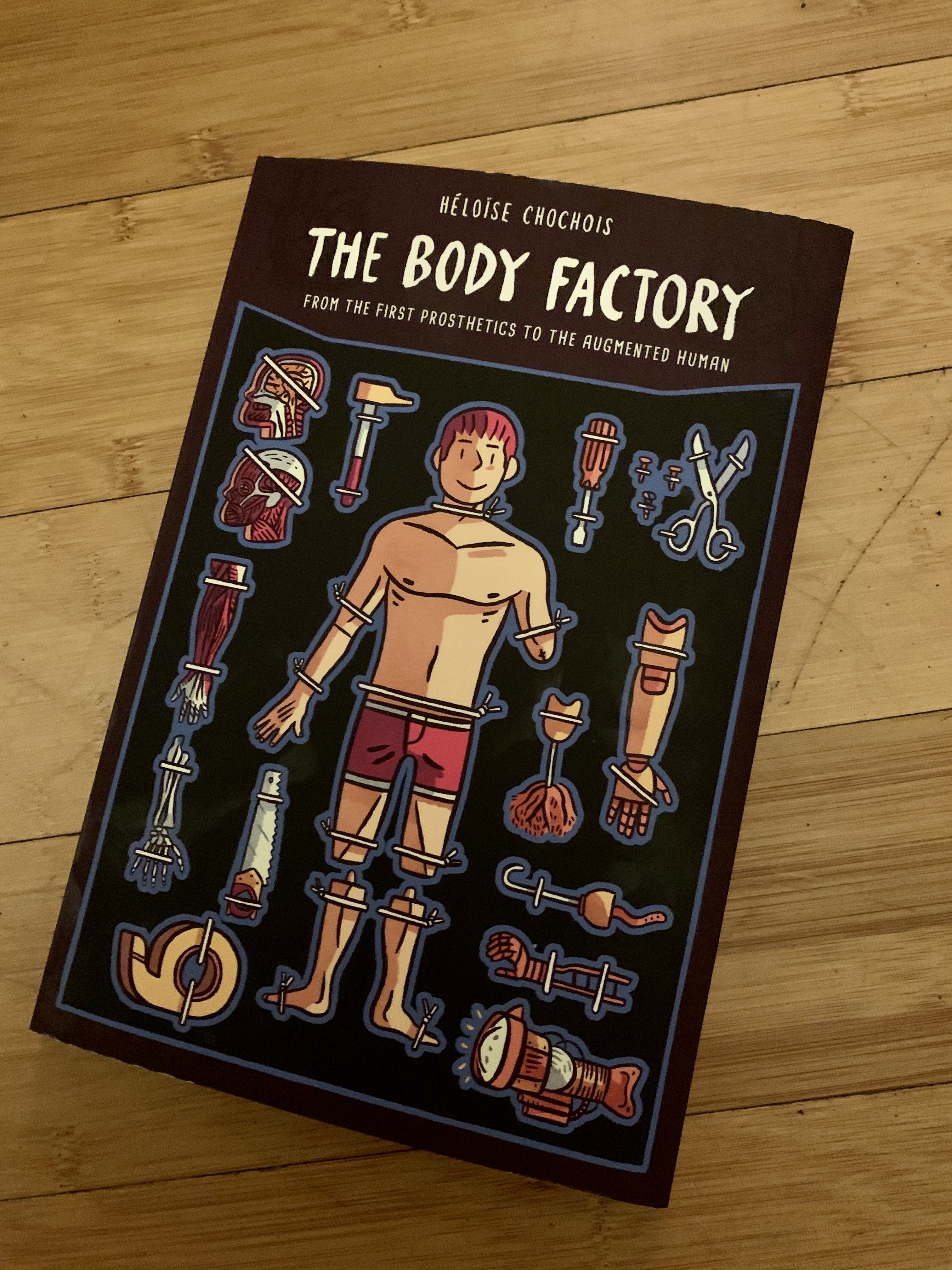

I felt the same tension while reading The Body Factory: From the First Prosthetics to the Augmented Human, a graphic novel by French writer and illustrator Héloïse Chochois (translated by Kendra Boileau). The book follows a young man who has his arm amputated after a motorcycle accident, and uses this event to tell the history of prosthetics and to speculate on what the future holds for the body.

The book itself isn’t terribly gory. The motorcycle accident happens offstage; the blood in the aftermath is rendered in black and white. It could just be pools of ink. There are clean-lined diagrams of the surgery he undergoes, detailing the layers of skin and nerve and bone that the surgeons need to cut through during the surgery. There are images of the brain and nerves that help to explain the young man’s experience of his phantom limb. They’re friendly images that seem to want you to understand them, that soften the inner workings of the body so that you can look closely.

I want to look closely, and I also want to look away. Now I can get a blood test while remaining conscious—in fact, while chatting with the phlebotomist. I want to see what they’re doing, see what my blood looks like in a tiny tube. But I never do. Instead I close my eyes or watch the wall.

What is it about the body that confuses me so much? In The Body Factory, I saw the image of the saw the surgeon uses, the way they wrap the muscles around the bone and stitch the stump closed—and I closed the book. Then I opened it again. Was it too much reality to bear? It’s also hard to read the sections that show the young man adjusting to life without his arm, trying to tear open sugar packets and tie his shoes.

Maybe it’s not the body itself that is the problem, but the knowledge that something went wrong and that’s why we’re looking at it from the inside. Seeing someone else’s pain, anticipating your own. Maybe it’s the combination of how fragile it all is, and how resilient, too. Which one of these, I’m wondering, makes me more uncomfortable?

I’m still not sure. I have now read The Body Factory three times, and just like with the blood draws, I’ve gotten better with practice. Each time I can look more closely at the drawings, appreciate the intricate weave of nerves, the way a tourniquet can prevent the brachial artery from flowing. I will tell you three times that this is all a miracle, that the body is breakable and strong, and still I want to look away, even from drawings on paper in oranges and reds, blacks and blues and greens.

Last night, I was looking around the house for the book so I could write this. “Oh, you mean the gross one?” my son asked. He pulled it out from underneath a stack of papers. Before he handed the book to me, he opened it up and took one more look.

Thanks, Cameron, for this essay on looking at the human body as parts–bones, blood, tissue–a kind of life unwrapped! I read this essay just after I woke up and checked the weather, and this for some reason, seems significant enough to mention. As the morning has gone on, and I’ve been looking at samples of how to write about the history of science, I came across an old review of a book on scurvy at Slate by historian Rebecca Onion. So, such an interesting contrast between the cover of “The Body Factory” with the smiling man with his tourniquets resembling bracelets and Onion’s review which has lines like these: “In the scorbutic body, as connective tissue fails, long-healed broken bones unknit themselves, and legs cramp so severely that the person cannot walk.” https://slate.com/culture/2016/12/jonathan-lambs-history-of-scurvy-reviewed.html

Thank you, Rachel! I’m looking forward to reading this. I also need to go look up “scorbutic”.

My wife watched her own c-section in a large teaching-hospital mirror the anesthesiologist rolled in because she had tried to bring a hand-mirror to hold up and see with. (Doc: No. That hand mirror is NOT going to be near my sterile field.) And she asked questions throughout (“What’s that purple thing? Why does the uterine muscle look like it’s wrapped in a spiral?”). She’s a muscian, btw. Eventually the doc just started narrating the entire procedure. Meanwhile I’m huddled behind the little curtain they put by her head to keep her from seeing (ironically, I guess).

Anesthesiologist, looking worried: Are you OK sir?

Me, probably blanched white: No. I don’t want to be here. I want to be out there (points at door) looking at posters of puppies and waiting for some totally clean person to verbally give me the good news.

My favorite exchange from the whole thing went like this. The doc is in the middle of moving various organs out of the way while discussing that the uterine muscles are in fact arranged in contrary-direction spirals to help push the baby into and through the birth canal.

My wife, interrupting: Ooo. What’s that bright yellow stuff that looks like chicken fat.

Doc: That’s your body fat.

Wife: Can you, um, just leave that out?

Doc, chuckling: Sorry. You need this to cushion your organs. You’ll thank me in 30 years. Trust me on this.