This post originally appeared in May of 2020.

A few days ago, I was walking idly along a mountainside near my house when I noticed the lower branches of a ponderosa pine, heavy with bullet-sized pollen cones. Intrigued by their purplish color, I plucked one, piercing it with my thumbnail. The juice came out magenta as a beet.

Natural inks have been enjoying something of a contemporary resurgence, at least in my Instagram feed. There, I had recently noticed that the Toronto Ink Company had teamed with New York Times illustrator Wendy MacNaughton to show kids how to make inks out of common kitchen items like black beans and blueberries. So why not pollen cones? I thought, loading my pockets with the sticky orbs.

Naturally, I didn’t do anything so practical as follow an ink recipe. I just got witchy, figuring I could cover them with water and boil them until the solution was sufficiently concentrated to produce a vivid stain. Having only one saucepan to my name, and feeling uncertain about the relative wisdom of boiling resinous cones of unknown toxicity in a container I use to make food, I piled the cones into a mason jar instead, filled it halfway with water, stuck it in the microwave, and watched.

Some witch.

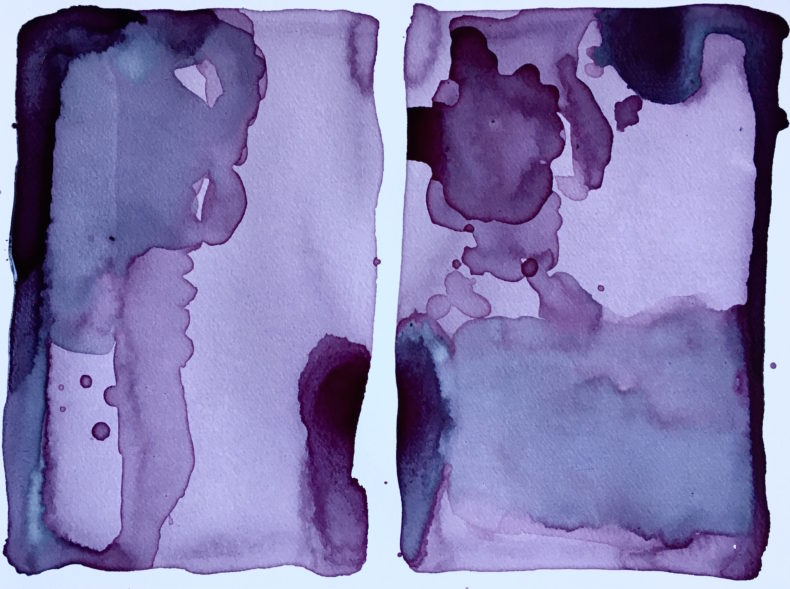

Every time the concoction seemed at risk of boiling over, I cracked the door and let it cool for a bit, then boiled again. Once it seemed sufficiently reduced to a concentrate, I poured this into a fresh jar, holding the pollen cones back with a fork. Then, I used a cheap paintbrush to blot wet puddles of my improvised ink onto watercolor paper and watched them change as they dried. The results were delightful—a saturated purple that shone with resin at its margins.

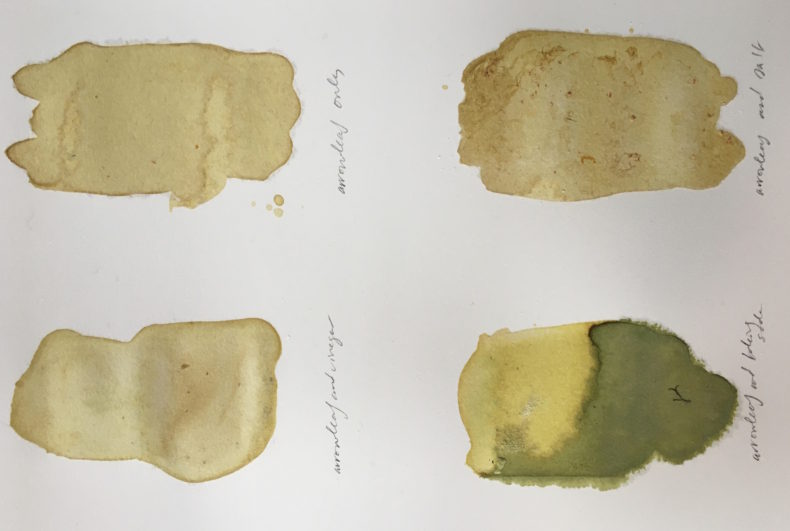

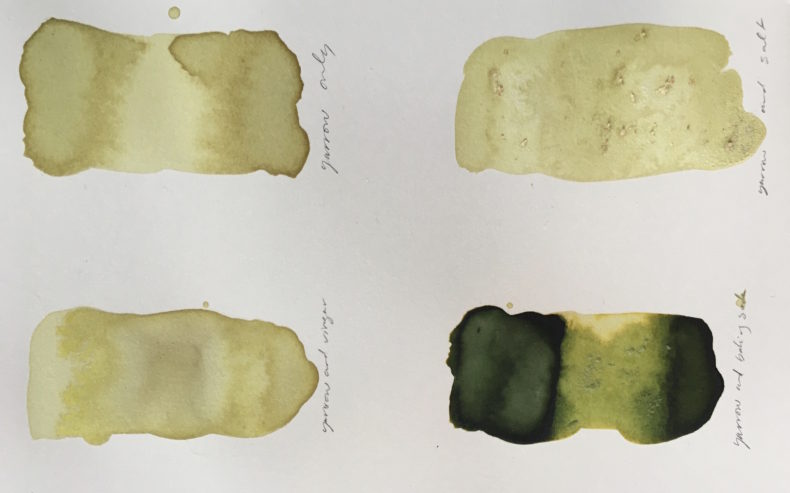

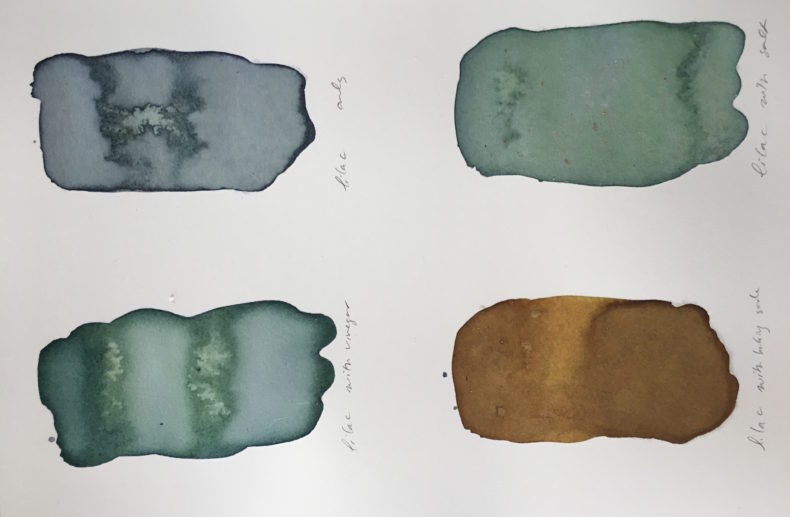

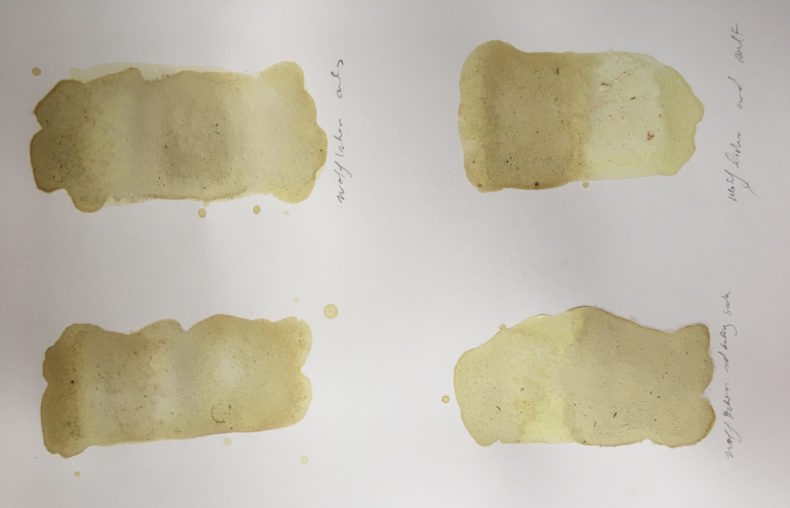

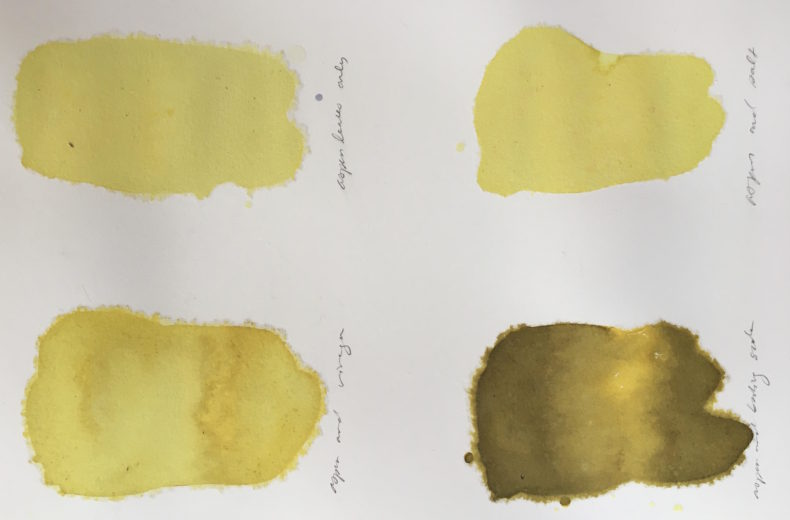

Thus encouraged, on a still and sunny day, I looked upon the field outside my house and resolved to paint it. Not all landscapes must be representational, and this one would be completely literal, made only from itself. First, I plucked several great golden sunflowery heads of arrowleaf balsamroot, growing by the driveway. Then, a handful of fluorescent green wolf lichen from dead pine boughs. A healthy wad of aspen leaves. A clutch of lilac blossoms. Three deep purple iris heads. Fragrant crushed yarrow leaves. Whole dandelion blossoms. Sticky conifer needles.

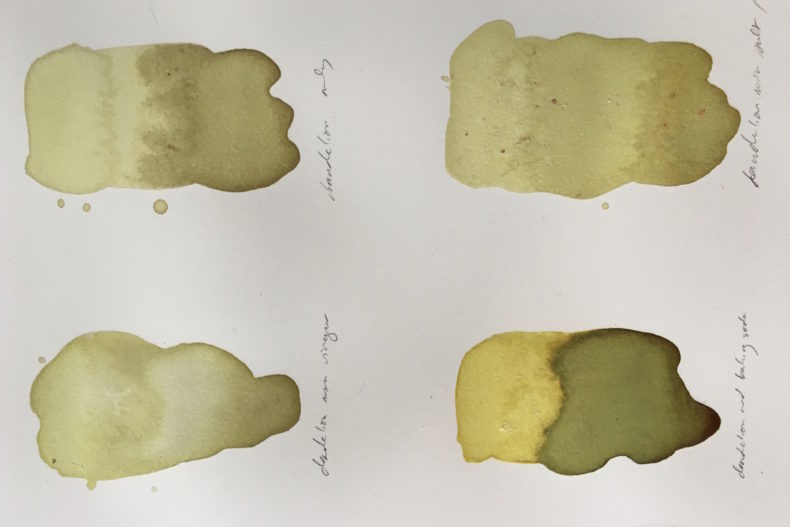

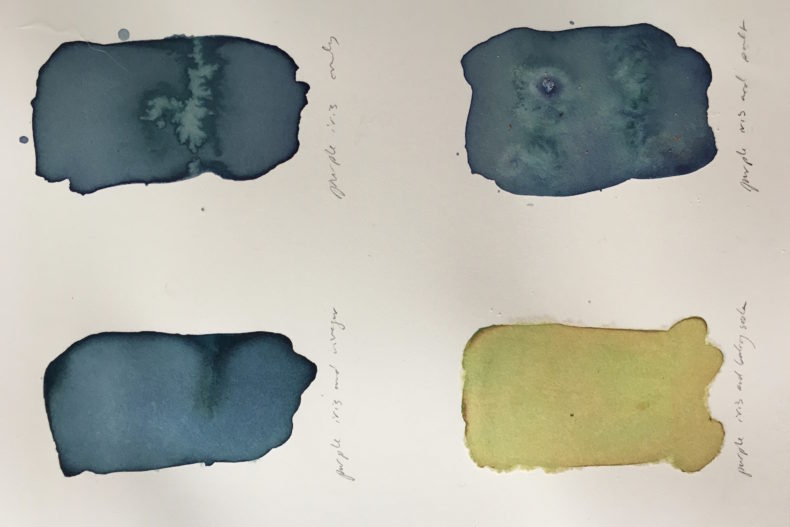

Each of these went into its own jar with enough water to cover it, then went through the same process as the pollen cones. I fixed a large sheet of watercolor paper to a masonite board with painters tape, and divided it into 32 sections with the same—four for each plant pigment. Within these, I gleefully made more blots. One, I left unadulterated. But upon the other three, I sprinkled salt, which causes interesting blots and blooms, or drizzled vinegar, or sprinkled baking soda, which can change the ink’s color. The lilac and iris shifted from gray and purple to hazy pink, then finally came to rest at saturated green and blue. For a moment, I forgot the microwave shortcut and felt my witchiness redeemed. Almost, anyway.

Here, dear readers, are the final results, subject to weathering by sun and other elements that wear on the ephemeral, even indoors. The corner of the mountain valley where I live, summarized in a handful of colors:

All blots and images courtesy of the author, with sincere apologies to the plants who gave their bits so that I might be entertained for a few hours.

Fascinating!

Such a beautiful post–it reminds me of a recent Smithsonian article that mentions how one scientist uses soil from a wildfire to make a range of ash-infused pigments. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/meet-western-soil-scientists-using-dirt-make-stunning-paints-180976796/

Ms Sturges comment reminded me of Greg Robert’s Sonoma Ash Project. Stunning Ash glazes rising from the devastation.

https://ceramicartsnetwork.org/ceramics-monthly/ceramic-art-and-artists/functional-pottery/clay-culture-sonoma-ash-project/

Thanks, Nancy! I love how the ash project article talks about how this kind of work might offer “hope for closure and reconnection.” Like Sarah’s painting with colors derived from leaves, blossoms, and needles near her house, soil and ash speaks of where it is from and what it has been through.