When I was in college my department offered a course in comparative anatomy. The idea was that you could learn a lot by comparing and contrasting different species. I was reminded of that course while reading Emily Willingham’s new book, Phallacy: Life Lessons from the Animal Penis, which is published tomorrow. The book offers a hilarious, enlightening and thought-provoking tour through the world of animal penises, but in the end, I can’t help thinking that the species we learn the most about is humans.

Emily is a friend of mine, and I’ve long admired her excellent work, so I was thrilled to receive an advance copy of her book. I invited her to LWON to talk about Phallacy and how she pulled it off.

Christie: What was the genesis of this book? How did you end up writing a book about animal penises?

Emily: I was working with my agent on an idea about the brain (which is now a book in progress) when I realized, somehow not having done so before, that I know a lot about penises. Not just from being around them, but as someone who did a postdoc in urology. So I sent her a quick email to that effect, and we were on the phone within the hour. It was amazing how fast it unfolded after that.

Christie: In the book’s introduction, you write about a childhood experience where a gardener at your grandmother’s house laid in wait for you, then got your attention and pulled down his pants and started masturbating. “He gestured to me, leering and threatening, trying to get me to come over to him,” you write. You were 12 and his behavior scared you, but you write that “He terrorized me, not his penis.” This seems like a running theme in the book: the consequence of our culture’s fixation on penises. Can you say a few words about the conflation of penises and masculinity?

Emily: Masculinity is a fluid concept, constrained and defined by sociocultural context. What is considered masculine is not the same across cultures, and what one culture might emphasize a lot can get little attention in another. That’s because people are so behaviorally and temperamentally variable from one person to the next, and culture changes over time and under different environmental influences. The human penis, on the other hand, is an anatomical structure that does not show this variability and complexity even in its function and is not a unique qualifier of masculinity. It is reductive to focus only on the penis as something that defines, categorizes, or damages a human being when our brains are the responsible parties.

Christie: You coined a word in this book, intromittum (plural, intromitta). Can you explain what these are and why it was necessary to create a new term?

Emily: I did coin it. I almost immediately began thinking about the issue of this structure that’s inserted into a partner to transmit gametes and realizing that defaulting to existing language would not capture two aspects: the full range of what these structures are and are made of, and the fact that they occur in animals that make sperm, those that make eggs, and those that make both. So it seemed inappropriate to use “penis” as a general term because of its usually narrow associations with a single sex and because a lot of these things, as genitalia researchers will point out, aren’t strictly or only penises. I wanted a term that was neutral and could be used regardless of sex, which this one is, in the singular and plural forms.

Christie: This book is laugh out loud funny, and it contains more than a little sarcasm. Was is challenging to strike the right tone here, or did it come naturally with this subject?

Emily: It was possibly the easiest part because I just let it fly–that’s my voice and how I deal with the world. That was a freeing experience. I mentally had to accept the fact that it could also be personally painful if people just hate it, but humor is subjective.

Christie: I must preface this by saying, I’m asking this in the context of your work researching and writing this book: Did you find a favorite penis?

Emily: I think my favorite was one on a snail that researchers sort of “rediscovered” despite its being really common in the local area. The penis is so outre on this animal that they at first thought it was some kind of wiggy-looking parasite. It’s also my favorite illustration in the book, one taken from an image that a Colombian-Australian artist named Maria Fernanda Cardoso created. She has done a lot of fascinating work around making tiny genitalia visible in her art.

Christie: You have a chapter on the uses for the penis, in which you wrote that when you teaching human anatomy to college students one of your classroom messages was that “the penis is a sperm delivery system.” But you go on to say that it’s not an accurate statement. What does that idea get wrong?

Emily: Like limiting our perspective of men to only penises, this description limits penises to just this function. In reality, they can have a lot of other functions, some associated with mating and some not, they don’t all deliver sperm, and not all sperm delivery systems are penises.

Christie: In your research, you encountered a lot of really crappy studies. Why do you think there’s so much shoddy research on penises and related topics?

Emily: A lot of reasons. One is that the authors purport to be answering one question when really, they’re answering something completely different (and often self-serving, in my opinion). The designs in the ones I highlight were a hot mess–really mixed, tiny participant groups, tools and tests that don’t address the putative question, conclusions that overreach to Mars. As an example, one study claiming to address “what women want in a penis” recruited 75 women, with the following self-identified distribution: thirty-six heterosexual, ten bisexual, eight homosexual, six asexual, three queer, and eleven none of the above/did not identify. Furthermore, 20 percent of the overall group had never had sexual intercourse. You can see that this is not a population that is likely to have been consistently engaging with penises on the regular being asked to offer an opinion on penises, but they were paid $20 bucks to participate, and to get that $20, they had to say that they were attracted to men. The “penises” were 3D-printed bright blue dildos, essentially, in a lot of different shapes and sizes, and the participants were asked to assess their preferences and then do their best to recall lengths and girths afterward. The authors concluded, among other things, that women prefer longer and thicker penises for a one-night-stand, despite the fact that 45 percent of participants had never had a one-night-stand. The authors also found that the participants “slightly underestimated” the size of the dildos after “recall delay,” which they used as an excuse to blame women everywhere for unfairly “exacerbating men’s anxieties about their penis size.”

Christie: This book isn’t just a survey of interesting animal penises (although it is that!) It’s also a cultural critique of science and the scientists who’ve set the research agenda in these fields. How have culture and human biases shaped what we know about penises and how these studies have been done?

Emily: Interesting that you ask this because I was just looking at a new study (embargoed until the 16th) showing that in preprints posted to biorxiv, the gender gap between men and women as corresponding authors is sizable and consistent. It’s 2020. Sigh.

One reason we know a lot about “male” genitalia is that for years, researchers dismissed the female side of copulatory engagement as uninteresting or having little to offer. It wasn’t until 1985 that an important book about sexual selection, by William Ebehard, took the first close look at how the interaction between genitalia during copulatory behaviors might be shaping both the male and the female structures.

Right about the same time, as I describe in the book, a review by a famous embryologist was still dismissing the female structures as probably irrelevant. Speaking from the perspective of evolutionary biology, that makes no damned sense because if the female structures are shaping the male’s structures, change would have to happen on both sides in an evolutionary call-and-response over time. If female structures remained unchanged, why would the males change at all? Yet, females were dismissed.

As I describe in Phallacy, for example, until a female biologist did so in 2005 (2005!), no one bothered to look at duck vaginas despite the notoriously complex-looking adaptive traits of the duck penis. When this biologist, Patricia Brennan, did examine duck vaginas, lo and behold, she found associated adaptations.

Yet even in the last couple of years, analyses of studies of genitalia still show underrepresentation of the females of species with two sexes. Science is not free of sociocultural influences, and as with all other things we do, how we practice it reflects who’s asking and answering the questions. Clearly, not having people with vaginas engaging in this research over the last couple of centuries has meant a narrative focused on penises. Adding insult to injury, a lot of research into the female side of the copulatory equation uses language such as “cryptic” and “concealment,” which…yeah, if you’re not looking, I guess it’s gonna stay hidden from you.

Christie: You have three sons, who do not appear in the book. (Here I must note that your dog does make an appearance in the book, though she doesn’t have a penis.) Is it embarrassing or cool to them that their mom wrote a book about penises? And have they read it?

Emily: They have put up with a lot, including, as I say in the acknowledgments, tolerating my dramatic readings of some of the funnier corners of the genitalia literature, plus the occasional feminist rant. We got the hardcover versions of the book the other day, and I gave each of them one. They are not given to a lot of flattery, and they all seemed to be genuinely proud to have a book that their mother had written. How they’ll feel about it once all the dust settles, I don’t know. Will they be walking around in their 30s and mention what my name is and have people say, “OH MY GOD YOUR MOTHER WROTE A BOOK ABOUT PENISES?!?” or just be met with blank looks? Which one of those is worse for a book author vs her children? I do not know.

Christie: What was your ambition for the book? What would you like readers to take away from it?

Emily: My ambition for the book was that it would impart three messages: that our penises are not especially impressive in the context of other animal penises, that the contours of the human penis argue for an emphasis on intimacy, not intimidation, and that the practice of science should not be abused as cover for self-interested sexual aspirations, something we could resolve in part by making it more inclusive. Oh, also, it would be great if it made people laugh here and there.

Christie: Well I can attest that you definitely succeeded in the last part.

Emily Willingham, Ph.D., is a science writer and author of Phallacy: Life Lessons from the Animal Penis, by Avery, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group. You can find her on Twitter as ejwillingham.

Credits: Frog: Ascaphus truei. Sketch by W. G. Kunze after Mattinson 2008.

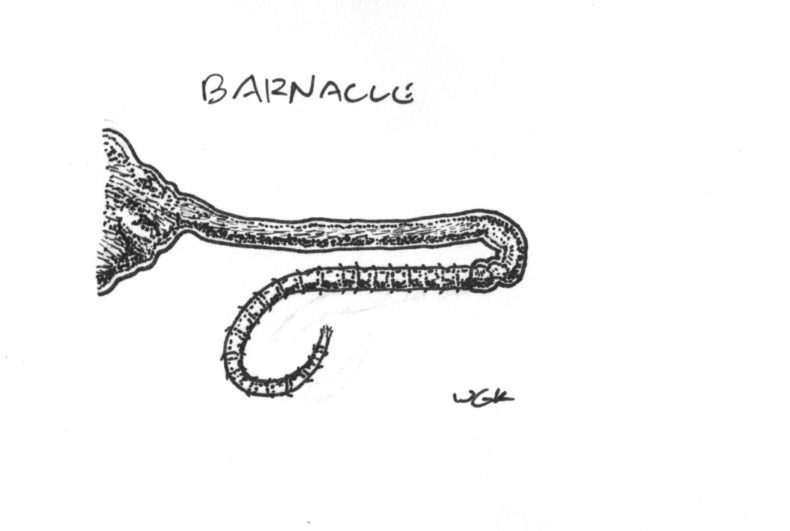

Barnacle penis (Ibla quadrivalvis): Sketch by W. G. Kunze after Darwin 1851.

Very interesting interview.Looking forward to reading the book!