My father isn’t Superman. He doesn’t wear shiny Spandex and a cape, he can’t fly. If he could, he would be out of there. Out of there immediately, flying up and out into the clean air.

The nursing home where my father lives is now crawling with Covid-19. Thirty-eight cases and counting, ten of those staff. His partner just died (not of the virus, interestingly, but she’s still just as gone) and he is alone as the nurses and administrators frantically wave their arms and try to contain the madness. His virus test was negative: It appears he has so far avoided infection–unless he’s gotten it in the four days since the swab was done. Which is certainly possible.

Someone wearing a lot of plastic puts a tray of food in his room now and then, and occasionally the nurse comes to give him his insulin shot. Sometimes she doesn’t come and he pushes the call button over and over, to no avail. (Eventually, someone shows up. He can’t go without the insulin, of course. They know that.) Nobody has taken him for a shower in more than a week, though the plastic woman left him an extra towel and washcloth, in case he wants to wipe himself down at the sink. His laundry is balled up in a bag on the floor—he might be out of clean clothes. (He can’t see, so it’s hard for him to tell.) The phone in his room is acting up—sometimes he’s unable to call out—but no one has come to fix it.

When I call the nurses’ station or the administrative office, I talk to people who are exhausted and falling apart themselves. Some sound on the edge of tears. They have to pretend to be on top of things, but they can’t help but admit they aren’t. I coax the horrifying statistics out of them, beg for someone to be my father’s advocate and to make sure he’s okay. They make mild promises, pulling out their hair, quickly hanging up.

I reach him despite the fickle phone, listen to his complaints. He doesn’t yet know his partner is dead—I can’t bear to tell him. (She’s been in the hospital for weeks; he’s still expecting a miracle.) When he last saw her, “she looked like she was sleeping,” he said. He squeezed her hand that day, she didn’t squeeze back. Since he can’t really see, he asked the rabbi in the room if she’d moved or opened her eyes at the sound of his voice. The rabbi told him the truth: No.

He is bored and smelly, and he’s unhappy that nobody took away last night’s food tray. He’s angry the nurses don’t come when he calls them to bring his pills, and that he doesn’t recognize the voices of people behind masks who occasionally peek in and then close the door and move on. The paper towel roll in the bathroom is empty. These are the things he’s focused on.

I’m focused on trying to help him from afar, and I’m failing in most respects, as I feel I have been for a while. Shipping him the wrong candy, the wrong electric toothbrush head, a ridiculous number of pens. (I didn’t notice it was a box of 80. He just needed, say, three.) Those were small failures, I realize. And then there’s now. I’m “high risk” myself and so can’t go get him and bring him home. That’s one of the big obstacles we’re facing…but there are many others. I don’t want to write the rest down because they overwhelm me. Every time I think about the mountain we’d have to climb to move him out of that room, out of that sad, sick place, my whole body hurts.

He asked me the other day if he’d ever see me again. My answer might have been a lie.

I can’t help but picture a building on fire, my father’s room still just outside the flames’ reach. (What a cliche. I’m even failing at original metaphors.) He knows there’s a fire. He must hear crackling and feel the warmth seeping under the door. Yet—and maybe this is a good thing—it seems he is oblivious to how fast and hard the structure is collapsing just outside. Mostly, he is annoyed at the smell of yesterday’s dinner and at that pile of laundry on the other bed that might be dirty or might be clean. And that it sure seems nobody around here is making an effort.

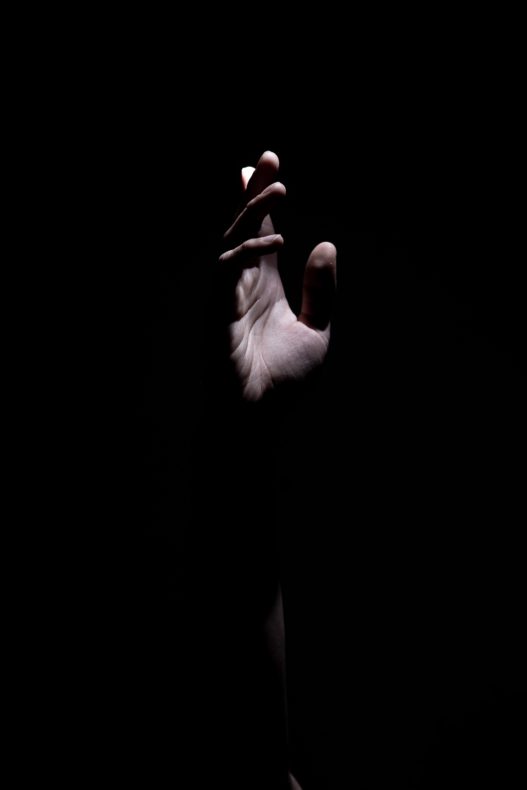

I imagine chaos happening in the halls, people in nightmarish paper suits moving in circles on the other side of the door to my father’s quiet room. I imagine my father sitting in a hard chair, shoes on, waiting to be rescued.

Photo by Akira Hojo on Unsplash

As I was reading your post, I was remembering work I used to do for the Long Term Care Ombudsman program. AARP has a good recent article on it. https://www.aarp.org/caregiving/health/info-2020/long-term-care-complaints-ombudsman.html Briefly they advocate for residents and are supposed to be able to enter any home in their area. That is being curtailed now. My sister, Ann Finkbeiner, tells me you can see my email address from this. If not, you can get it from her. I would be happy to discuss this program more, if you are interested. It was a badly needed program when it was started and even more urgently needed now, but it does have some idiosyncrasies.

Thanks so much, Gail–and appreciate the follow-up correspondence!

Jennifer, My heart goes out to you and your father. This time, while nothing seems to work to halt this deadly virus, everyone there is working to prevent or rescue people from this virus. I’m sorry you, with your remarkable ability to express this in such poignant words, can’t make this go away or get better with these words. Thank you for bringing us into your and your father’s world, may he be protected, and may you know you are also doing the most that you can to comfort him and give him a sense of control. Virtual hugs, prayers. Nan

My mother died in a nursing home ten months ago. Every single day during this crisis I have imagined how life would be for her and the others where she lived. I am very sorry you’re going through this and I admire your courage that enabled you to convey this important message.

Thanks for the kind comments. I know I am not alone!