“There is an aspect to this story that is weirder than you can imagine.”

That sentence was e-mailed to me by a geologist, Jan Kramers, at the University of Johannesburg in the waning days of 2017. I had e-mailed him about a paper of his in Geochimica et Cosmochmica Acta. The title of the paper had caught my eye: “Petrography of the carbonaceous, diamond-bearing stone ‘Hypatia’ from southwest Egypt: A contribution to the debate on its origin.”

I think it was the name, “Hypatia.” It struck me as celestial, mysterious. Hypatia, I learned as I scrambled and stumbled by way through the paper’s dense geochemistry, is the name of pieces of what was once a single stone, found in southwest Egypt in 1996 by an Egyptian gem hunter and writer named Dr. Aly A. Barakat.

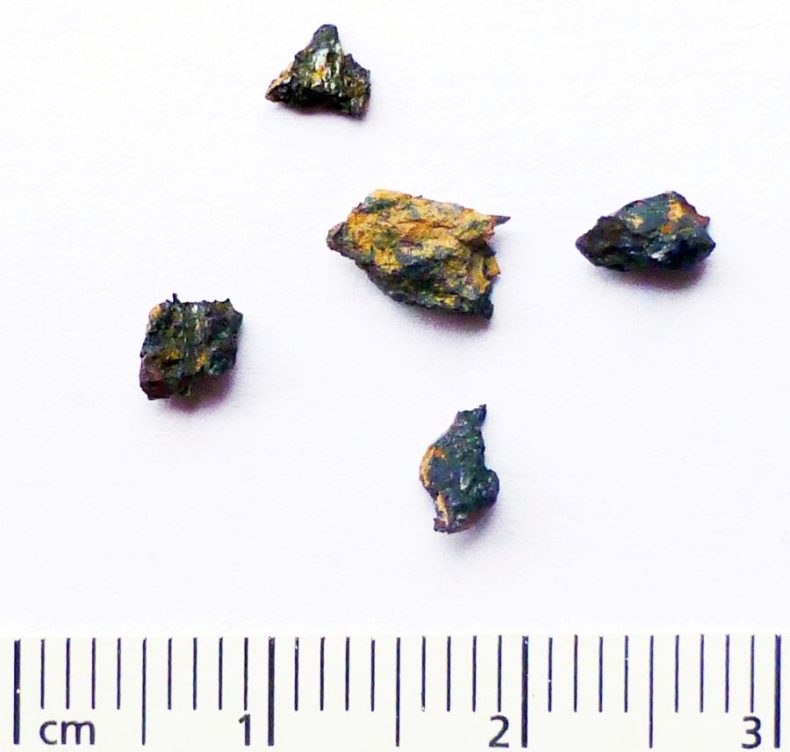

As stones go, it’s a strange one, although you wouldn’t tell by looking. Its fragments are drab, jagged, crumb-sized bits of rust-flecked gray. It was found in a nearly featureless, windswept desert and its mineral makeup didn’t match anything in the nearby geology, hinting that it might have landed there as a meteorite. Yet even for an extraterrestrial object, its makeup is unusual. It possesses enormous amounts of carbon and relatively little silicon, which is the reverse of what’s typically found in meteorites.

In 2013, Kramers and colleagues announced in Earth and Planetary Science Letters that it was actually a tiny piece of comet nucleus that had fallen to Earth some time long ago. Their 2017 paper revealed that much of its carbon was made of polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), the stuff interstellar dust is made of. The intense heat and pressure generated as this alien rock hurtled toward and hit the Egyptian desert transformed some of those PAHs into microdiamonds, forming a kind of sooty diamond crust around the stone that protected it from the withering desert until Barakat dug it up. The impact may also have been responsible for the numerous tiny, jewel-like pieces of glass strewn throughout western Egypt and eastern Libya known as Libyan desert glass.

The University of Johannesburg issued a press release accompanying the paper, which claimed Hypatia’s specific geochemical ratios suggested it predates the creation of our solar system, and that’s the headline that a few media outlets picked up on. But it was a throwaway mention in the paper, omitted from the press release, that intrigued me: “At the time of writing, the whereabouts of less than 4 g of Hypatia’s matter are known to us.”

So that’s why I first e-mailed Kramers in December 2017, asking where the rest of it had gone. He asked me to Skype him. When I did, he told me one of the craziest damn stories I’ve ever heard.

Here is the tale of Hypatia, as told to me by Kramers.

When Barakat first found the stone, it was a single 30-gram chunk. He realized it was unusual and attempted his own analyses of it, which he published in a 2012 book, “The Precious Gift of Meteorites and Meteorite Impact Processes.” Realizing he had reached the limits of his expertise, he reached out to professional geologists, including Kramers’ lab in South Africa and another outfit in France. Barakat sent each of these labs small shards of the original stone for analysis, which led to the 2013 paper formally proposing its extraterrestrial origin. In the process they named it Hypatia after Hypatia of Alexandria, an early mathematician and astronomer.

Despite that, Hypatia has never officially been recognized as a meteorite. An international organization called the Meteoritical Society is responsible for ordaining otherwise ordinary hunks of rock as celestial objects, and for this they have strict guidelines. What’s known as the “20/20 rule” specifies that, in order to be considered for meteoritical classification, either 20% or 20 grams of the purported space rock’s original mass be donated to a respectable museum or archive for research and posterity.

Twenty percent of the original 30-gram rock would be 6 grams. Kramers has about a gram; the French team has another couple of grams. Barakat himself hasn’t parted with any more of it. And there may be reason to believe he might not be in possession of it anymore, Kramers told me. Around the same time Kramers’ team published their 2013 paper, mass political protests were sweeping through Egypt, ultimately deposing President Mohamed Morsi. In their wake, the Egyptian military quickly rose to power. It was at this time that Barakat himself fell out of contact for several years.

Kramers told me he thinks it’s possible that nefarious forces, having read that the stone contains microdiamonds and could be valuable, may have taken possession of Hypatia. Barakat has since resurfaced and still regularly posts on his blog, but scientists have yet to receive any more fragments from the original stone. If Barakat still has the rest of the stone, it’s not clear why he hasn’t archived it, or at least a large chunk of it, with a museum in order to have it properly classified by the Meteoritical Society.

Yet there’s an extraordinary reason Kramers thinks Hypatia may have fallen into less scrupulous hands. A few years back, a skin cream showed up on the British market called Celestial Black Diamond Cream. A 1.7-fluid-ounce jar of the stuff will set you back a cool $1,000 at online retailers. According to its product description, its “black diamond particles … provide the optimum environment for collagen and hyaluronic acid production, improving elasticity, plumpness, hydration, texture and tone.”

Its makers claim that the diamond particles in the product “were believed to have formed in space. ” As in, they came from a meteorite. And Kramers told me he has reason to believe the cosmetics company is sourcing this ingredient from Egypt.

For what it’s worth, “diamond powder” is indeed listed in the product’s ingredients — right between hyaluronic acid and peg-7 hydrogenated castor oil — and British cosmetics is a well-regulated industry.

So, black diamonds. From a meteorite. From Egypt.

Could someone be grinding bits of a rare fallen comet nucleus into a fine powder and selling it as a luxury skin cream? Kramers believes it’s a distinct possibility.

⁂

I called and e-mailed the company that makes the cream and never got a response. I also called and e-mailed a variety of meteorite researchers asking whether they thought the story could be legit, and I was given the brush-off. Finally, last year I cornered geochemist Alan Rubin, co-curator of the UCLA Meteorite Collection, and asked him what he thought. He asked me to send him the 2017 paper, which I did. Rubin e-mailed me back to say he agrees the stone is weird, but he’s not certain it’s even a meteorite. Nor is he convinced of the cosmic cosmetics connection.

And that’s where I left it. I simply didn’t have the time to chase this story to the ends of the earth, and other projects came up.

Hypatia is a weird rock. It may have come from outer space, or it may not have. It may have been seized by rogue elements in Egypt, or it may not have. It may be the namesake ingredient of a ludicrously expensive skin cream, or it may not be.

Kramers was right, though. There were aspects of Hypatia’s story that were weirder than I could have imagined.

Michael Price is a freelance writer and contributing correspondent for Science magazine based in San Diego

Photo credit: fragments of Hypatia, by Mario di Martino, INAF Osservatorio Astrofysico di Torino