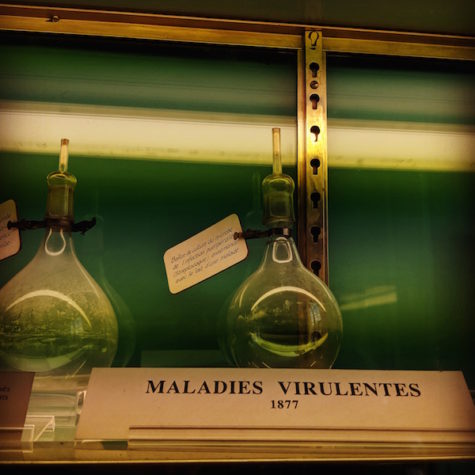

A few months ago, I visited the Pasteur Institute, a research center in Paris dedicated to the prevention and treatment of infectious diseases. The trip included a tour of the apartment and crypt of Louis Pasteur, the 19th century French chemist and microbiologist who developed vaccines against rabies and anthrax.

My favorite part of the tour was Pasteur’s bathroom. I thoroughly enjoyed imagining Pasteur splashing about in his porcelain basin, or soaking in the bathtub supplied with hot water from impressively modern plumbing (for the 1800s). It must have been nice to take a hot bath after a long day harvesting spinal cords from rabid rabbits.

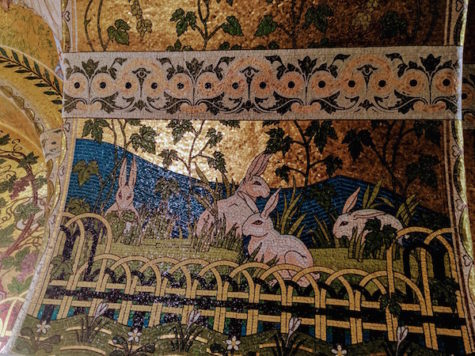

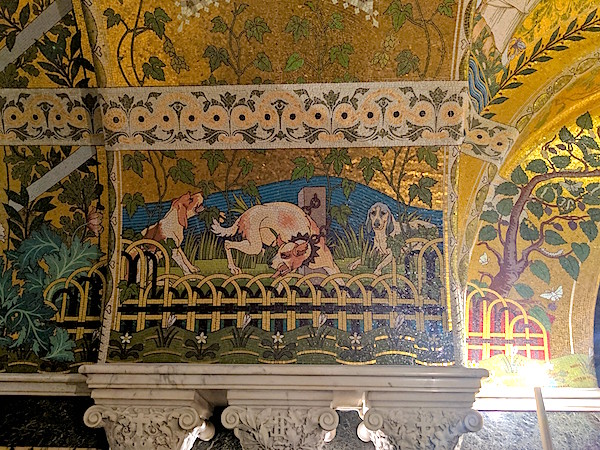

From the rabbit spinal cords, Pasteur extracted a weakened version of the rabies virus which he used to develop a rabies vaccine. In his crypt, where he is buried with his wife, gilt mosaics depict the rabbits and dogs Pasteur used in his experiments, as well as a 9 year-old boy who received the first human dose of the vaccine, after being mauled by a rabid dog.

There are also angels who hold up signs that say Charity, Science, Faith, and Hope. My first thought when I saw the angels was of taxi drivers waiting for passengers at Heaven’s airport: Bonjour, Monsieur Pasteur. Your cab awaits.

But Pasteur was no angel. He lied about his methods, studies of his laboratory notebooks by Princeton historian Gerald Geison have since shown. His decision to give a nine year-old boy the first dose of rabies vaccine was also questionable, ethicists say. Pasteur claimed he’d tested the vaccine on at least 50 dogs before giving it to the boy, but never clarified how many of those dogs had actually been exposed to the virus beforehand. (Also: poor rabbits, dogs, sheep, etc…)

Despite his flaws, Pasteur made an incalculable contribution to science and public health by demonstrating that vaccines can effectively prevent horrific plagues in both animals and people. Actually, it’s not incalculable. According to the World Health Organization, the vaccines Pasteur’s work inspired save about 3 million lives each year.