First must have come listening

to the wind or regarding

the movements of animals,

then monitoring the stars

and sometime after that

scrutinizing fire;

but somewhere in there belongs

watching the progress of a river…

Billy Collins, “The List of Ancient Pastimes”

Most of the last couple weeks I’ve been sleeping on the ground. I stayed in southern Utah canyons long enough to watch palaces of cottonwood trees go from green to gold. It happened fast, high desert washes flaring in a matter days.

Watching is something we’ve been doing since the beginning, one of the traits of being human. Something catches our eye, not predator or prey, but a swirl in water, a turning of stars, and we stare at it, enchanted. It is like waking up for the first time, seeing where you are. Watch for long enough and you witness change too slow for the human eye. Horsetails breeze from one side of the sky to the next as veins in leaves tighten, pigment brightening while chlorophyll dies.

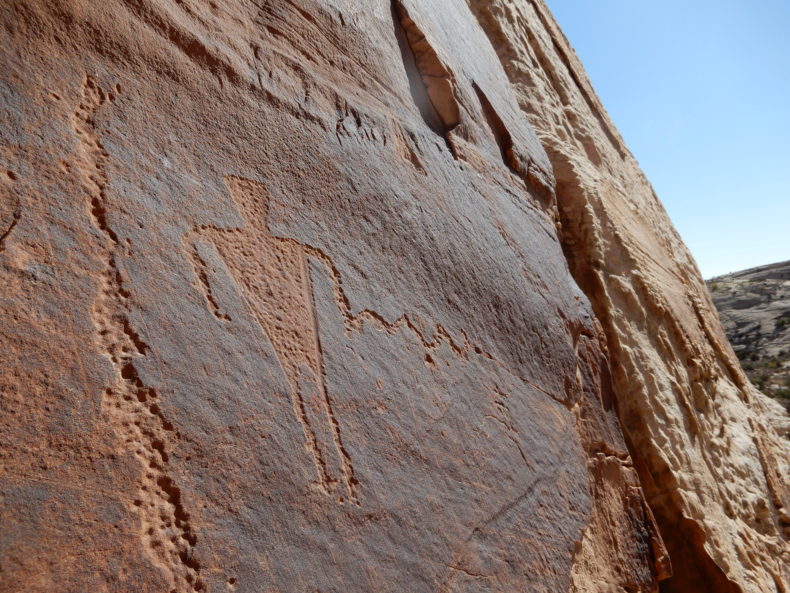

Part of these couple of weeks, I was co-teaching an archaeological field program in southeast Utah, days of marching up and down canyons, reaching rock horns hundreds of feet in the air. We looked at petroglyphs dating back hundreds to many thousands of years. The co-instructor was Hopi archaeologist Lyle Balenquah, and he offered theories as to a sandstone wall with a 15-foot line of small human figures pecked into it, all going the same direction, some with hands, some with gear on their backs, some with penises, most without, one playing a flute, and, intermittently, a figure bigger than the others, with a bent-neck staff as if driving them. The line had 179 figures. Slaves on the march, migrants moving east to west, a village visiting another and commemorating the moment.

Some of the group drew to particular images, a tiny figure with what looked like a duck on its head, or a pair of deer with boxy bodies bounding forward. Others stood back and looked at the whole of the panel, many hundreds of figures, humans, animals, symbols, clan signs.

Some people sat on boulders looking away from the panel, seeing miles-long slabs of rock lifted as if giants were pressing from below.

I come to places like this to take in the view, no matter how small or large. Same for everyone else in the group, including Balenquah. As part of the program, we hiked up the side of one of the two Bears Ears, a pair of twin, red buttes rising to 9,000 feet. They listen across the Colorado Plateau as if a bear’s head were coming over a rise, ears perked. Near the top of one ear, our view encompassed desert and distant mountains. Balenquah pointed to a skim of horizon, a shade of pale 125 miles away, the Hopi Mesas in Arizona. He said he could see his home from here. I looked the other way, east and barely north, finding a solitary peak shaped like a prism, the last of the Rocky Mountains near the edge of Colorado. I pointed and said I could see my home on the northwest flank of the lone peak, 95 miles away.

This is a viewshed, the terrain visible from a location, all that is within line-of-sight. His place and mine were 200 miles apart and we could see both at the same time. We were floating for a moment above the world, seeing past its nearest horizons. We were neighbors.

Balenquah is Hopi, Greasewood Clan, living at Bacavi, one of four villages on Third Mesa in northeast Arizona. He said he knew of memories from when his people lived in cliff dwellings in this part of Utah, and he explained that the memories were dim. This was 800 years ago at the least, one part of a complex indigenous history, a time of prosperity, drought, poverty and warfare. The people, Balenquah’s ancestors, are known to the Navajo as Anasazi, a name too complex to pick apart except around a fire on a chilly evening. To him, they are Hisatsinom, the people who would become Hopi. They lived here for many centuries and migrated away during a time of turmoil and environmental instability, resettling in the south, a place he could see from here. So much for the mystery of the vanished Anasazi. They moved one horizon over.

At night, we sat around the fire and talked, comparing what we knew about ancient corn species and styles of pre-Columbian ceramics. Our viewshed was not just space, but time. Participants listened to Hopi names for places, and a story about mountain lions, another about ravens. We looked farther than our own moment in history, recalling what we’d been finding during our hikes, flakes of stone, painted and pinch-coiled potsherds, handprints on walls. We talked about geologic formations and spoke of animals as if they were people. Everyone had an owl story.

Nights became colder, first frost, second frost, canyon bottom at dawn below 20 degrees. Our tents were glazed white as we started making fires in the morning. Standing in close, we’d leave a gap between us where smoke could escape, rising into dandelion-colored cottonwoods, drifting through the mouth of a canyon decorated with ruins. When the sun reached us, we climbed above camp and found one of the ruins, a small granary, doorstone still in place. It looked like an eye. We took our positions around it, some coming in close, careful with footsteps, others keeping their distance, taking in the scope of the land. We were all eyes ourselves, all watchers, as warm morning light gave way to desert noon.

Photos: Craig Childs

Wonderful piece, Craig. It really resonated with me. On the trip I was so drawn to the distances.

High places show how distant sites connect in space. They also seem to connect to the past, the weight of all the souls that saw what you can see, and more. It is a privilege to stand in those places. Thanks for putting it to words, so that more people can “see” it, too.

I live in a geographical flood plain in Eastern Kentucky, and the surrounding hills provide a much needed perspective over the landscape. Great piece, thanks!