This is an update to a guest post that ran on December 12, 2018.

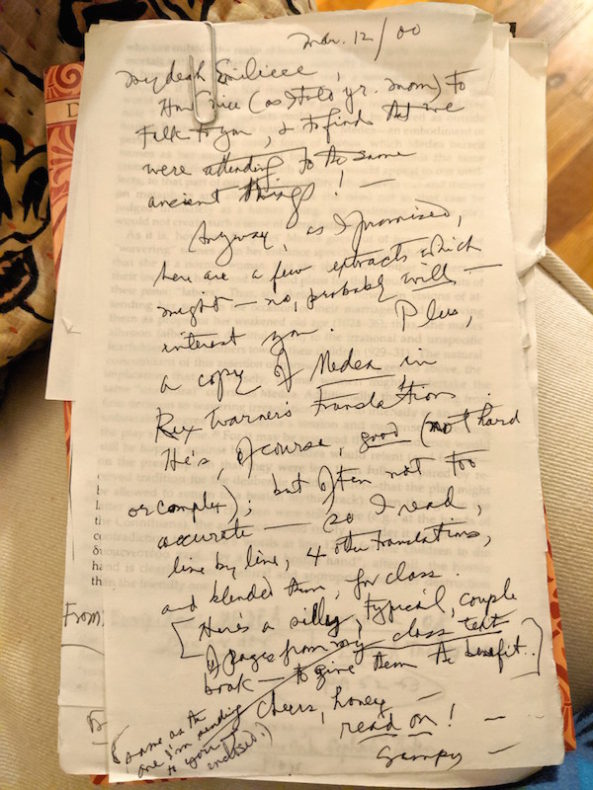

A few days ago, I found the following letter from my grandfather, Donald Pearce, in my parents’ bookshelves. It was tucked into a copy of Medea which he sent to me when I was a high school sophomore. ( I was precisely the kind of teenager who loved Medea.)

Grampy taught English literature at UC Santa Barbara, but always said he had more fun teaching at the local adult education center. I think he found the students a little more varied in their life experiences, and more interesting.

As you can tell from this letter — all those em dashes and exclamation points! — Grampy didn’t just read. He dove into texts headfirst and swam around in them, splashing about with glee. He spread his infectious enthusiasm right up until his death, which occurred about a year after he sent me this letter.

These days, the longing I feel for my grandparents feels less like waves, and more like a wellspring. The window tree in my backyard is showering gold again, so thought I’d repost what I wrote after my Nana died in 2017. Cheers, honey. Read on!

The Window Tree

All year long I’ve been haunted by a poem. When I sit down to work or go for a walk, it drifts into my mind:

Tree at my window, window tree

My sash is lowered when night comes on

But let there never be curtain drawn

Between you and me.

There she is, wearing the tattered yellow paisley bathrobe that used to hang on my grandfather’s broad shoulders. Her silvery bob is a little wild, static electricity from her slippers raising stray hairs into a halo.

Vague dream head lifted out of the ground,

And thing next most diffuse to cloud,

Not all your light tongues talking aloud

Could be profound.

It’s been almost exactly a year now since my grandmother died, but I still sometimes wonder if the snatches of verse in my head are a message or echo – from her, from somewhere.

But tree, I have seen you taken and tossed,

And if you have seen me when I slept,

You have seen me when I was taken and swept

And all but lost.

Let me explain. When I was in my twenties, I lived with my grandmother for about a year. She didn’t sleep well. One morning, after a particularly rough night, she padded into the kitchen carrying a book of verse and opened it to Robert Frost’s “Tree at my Window.”

Nana was an atheist, her abhorrence of religion rooted in an abusive upbringing by Southern Baptists. But she believed in poetry. Before he died, my grandfather read her poetry every night to help her fall asleep. In the morning, poems brought her back from childhood nightmares to fresh coffee and orange juice, to the latest New York Review of Books, to her two pugs, Buddy and Yo Yo. And, blessedly, to me.

The morning I found out Nana was dying, the clouds were oddly dark and dense, like cotton batting. My sister and I drove from Northern California in a downpour and joined my parents at Cottage Hospital in Santa Barbara.

Nana delayed taking the narcotics that would ease her pain – she didn’t want to fall asleep without saying goodbye. My mother stayed up with her all night as she waited for all her children and grandchildren to arrive. To ease her anxiety, my mother reminded Nana of her favorite dream, one of the few recurring dreams Nana had that weren’t nightmares. In it, Nana was skating on a frozen river through a forest, snow all around. It was like flying, Nana said. Breath in, swish, breath out, glide.

That day she put our heads together,

Fate had her imagination about her,

Your head so much concerned with outer,

Mine with inner, weather.

Once everyone arrived, we laid our hands on her body as if to steady it, laid our hands on each other’s shoulders to steady each other. She smelled sweet, like the shampoo she liked, and her hair was combed back from her forehead. When she died, her hazel eyes were open. I held her hands as they grew cold, as she turned white as a shell.

Nana’s death was as good as most people can hope for, eighty-nine and surrounded by family. But the transformation from person to body was still jarring. When I learned she’d decided to donate her body to be dissected by medical students, it felt like a smooth, blank wall. Impenetrable.

Tree at my window, window tree

My sash is lowered when night comes on

But let there never be curtain drawn

Between you and me.

What curtain separated us? I’d never thought very seriously about what divides the living from the dead. The closest I’d come to an answer was a story I wrote about a test to detect consciousness in people with locked-in syndrome. Scientists apply a magnetic pulse to the brain, then record the electrical echoes that come back. If a person has no conscious awareness, their reasoning goes, the echoes will be devoid of complex structure, like the repetitive ripples from a pebble dropped into a pond. Or, they won’t come back at all.

Vague dream head lifted out of the ground,

And thing next most diffuse to cloud,

Not all your light tongues talking aloud

Could be profound.

Did the ripples of Nana’s consciousness grow less complex, then just end? I imagine ice softening and breaking up beneath her skates. I hope she glided off instead.

When the nurses came in after Nana died and asked if we needed a spiritual advisor, my family laughed. No, Nana would come back from the dead and haunt us, we said.

She never has come back, although there have been times this year when I thought I felt her presence. But the poem is still here, her longing to connect.

But tree, I have seen you taken and tossed,

And if you have seen me when I slept,

You have seen me when I was taken and swept

And all but lost.

I keep reaching for my phone to call her. Last week, I wanted to tell her about a story I was writing, about a pulsating layer of charged ions high above Earth called the ionosphere. She would have loved the frosty vocabulary of this science: ionospheric scintillation, throat aurora, incoherent scatter radar. I wanted to tell her how the ionosphere reflects radio waves back to Earth; how the echoes we need to communicate can be disrupted by a solar flare.

If I could call or write, I’d tell Nana about the massive walnut tree that shades the house where I live with my boyfriend, whom she never met. The tree shades our house in summer, keeping it cool, and turns bright yellow in autumn, showering gold. In winter, it drops its leaves, letting the sunshine through and keeping us warm. Now, I’d tell her, I have a window tree of my own.

That day she put our heads together,

Fate had her imagination about her,

Your head so much concerned with outer,

Mine with inner, weather.

Beautiful and touching.

Saving this beautiful, touching story. How fortunate you were to have such lovely grands. How fortunate we are that you shared them.