I dream about books.

I dream about books.

Not about reading them, or even writing them. I dream, while still partly awake, about stacks of old books being carted off before I’ve had the chance to scour their titles or flip through their pages. I want to know what I’m losing, but there’s no time. I’m grieving.

We’d talked about it plenty, as a hypothetical. But when the time suddenly came to move my dad and step-mom out of Dad’s condo, where he’d lived for 40 years, into a much smaller, furnished, assisted-living rental, I had less than I week to get him ready.

And so now I sleep-fret over the mad rush to give away almost everything he owned. The book angst is especially haunting.

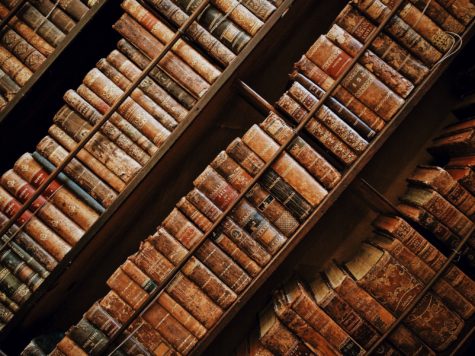

My dad should have been an English professor. His love of literature has always buoyed him. Although now he relies on audiobooks, his eyes defunct, books remain his lifeline, one of few things that still brings joy. Over the years he collected hundreds of volumes, mostly classics. His living room walls were always nonstop hardcovers, picked up at used-book stores around Chicago or saved from way back when. In another room, more shelves, more books. Tops of closets were book annexes.

I had about 72 hours to gut the condo. A cleaning crew would come soon to scrub away 40 years of grime; painters would slap clean white over dirty to “freshen up” the place for a quick sale. The bookcases loomed. I worked around them, frantically filling boxes and bags for charity and trash. Almost all the furniture was going to the only thrift outfit that could pick it all up on short notice. There was no time to sell much. A quick posting on Craigslist brought a buyer for the magnifying lamp and the guitar–he talked me down to $15 for the instrument, a heart crusher. (Dad used to play it all the time, perched awkwardly on the edge of the couch. I sang melody, my brother harmonized. Folky stuff. We weren’t half bad.)

But it had to go. I was out of time. Yes, the books, too. Last but not least.

I’ve been trying to understand all the feelings surrounding this emptying of my father’s nest.

There’s the obvious sadness at ushering a parent into his/her last phase, seeing a life whittled down to the basics. Plus, “things” have memories attached: We wrestled around on that couch, recorded songs and silly noises (we were inclined toward toilet flushes) on that tape deck, built forts with those chairs and blankets. Dad still had a dozen suits from his working days, polyester browns and light blues, with horrendous ties–there must have been 50–to match. His insistence that we “keep a few outfits, just in case”–as if they’d still fit his much-diminished form, as if he had somewhere dressy to go–made me want to cry.

And, of course, the books–beautiful, sturdy things that helped shape the person I’ve become.

In behavioral economics there’s something called the endowment effect: When we own something, we see it as having more value than others may apply to it (which explains why items are often overpriced at a yard sale). Few of my dad’s possessions had much monetary worth; the books were no exception. Still, they were his great pleasure and, by extension, mine. In a sense they were the walls that held up my father’s home.

He seemed relatively unfazed by the whittle-down process; perhaps years of blindness and gradual memory loss had dampened my dad’s connection to his physical things. I was grateful for that. But for me, the pain was very real. “Loss aversion” is common, of course: Studies of brain activity in the centers that process value and reward suggest losses hurt about twice as much as gains feel good. I can attest to that math.

So I looked for ways to feel better. Stoicism, an ancient Greek philosophy from around 300 B.C., offers that if you lose something important or precious, you can try imagining you never owned it to reduce its value in your mind. It goes for people, too, apparently: Pretend the person was a stranger to dampen the pain of their loss.

I can’t fathom actually applying the strategy to losing another human being. But for books, sure, let’s say the whole lot of them was borrowed; we’d had daily access to a wonderful library for years–how nice for us!–but the books had all come due. Returning them should feel freeing, even, something to cross off the to-do list. It was someone else’s turn to enjoy them.

It was more than letting go of ownership, though. I was very young when my parents divorced. My dad’s place was the only static thing in my world as my mom and stepdad moved us from city to city, house to house, school to school. Dad’s book wall could have been a painting. For me, that stable image, each book in its place, was a great comfort.

My own bookcases, though less static in content, are also full up, with overflow stacks on the floor. Still, I brought home a few titles from Dad’s shelves that day: The Brothers Karamazov, one of his favorites, All Quiet on the Western Front, one of mine. Some Tolstoy, Mark Twain, and a volume of limericks [inappropriate, of course] that used to make my brother and me giggle. (Nude Yoga, also giggle inducing, stayed behind.) A Byron anthology from which Dad can still recite without a glance at the page. And, of course, I salvaged all family-penned books (my Great-Uncle Meyer Levin was especially prolific).

Lastly, I kept a fat volume of Grimm’s Fairytales, with my nephews in mind. I used to scour its weird stories for the creepiest bits. A scene from one tale–in which crows, or maybe vultures, pecked the eyes out of a dead man’s head–has stayed with me, no doubt because I turned back to it over and over in horrified glee.

Now, I lie in bed nights thinking of the books I let go. There were so many of those scuffed leather-bound volumes–you know the kind, with the tiny print and pages like onion skin. And I can’t help but recall the painfully unfriendly bookshop owner (an anomaly, no?) filling his wheeled cart without ceremony or even empathy, making a dozen trips to his truck to unload. I remember how he rushed, avoiding my eyes, as if worried I’d suddenly change my mind and take it all back.

How does one price a thinking man’s literary life and a child’s memories of home? Any amount I might have asked for would have reflected something other than cash value. There was no point.

The exact titles lost, at least, are becoming blurry with time. It’s a small kindness of my failing memory that lets me, finally, fall asleep.

—-

Photos by Roman Kraft and Fred Pixlab from UNSPLASH

Nice

Very moving piece. Having helped my parents move several times and now downsizing a large library myself, I am very familiar with the nostalgia and sense of loss one experiences in parting with beloved books that remind one of their association with life passages.