Ann: The first thing I have to say is, that is a glorious title. Was it yours? I ask because with every book I’ve written, the title was a matter of intense negotiations which I usually lost, and I wonder how you got away with such elegance and relevance both.

Chris: It was my editor’s choice, despite it being one of two words on a post-it-note attached to my computer I used to remind me while writing (the other was Humility). We went back and forth for weeks with me in denial about how important a title is and also being cynical in assuming it would have to be something I hated. All along I was fortunate to have an editor (Bria Sandford) who not only got what I wanted to write, but helped me write it, even though I think some of the decisions we made wouldn’t have been approved by marketing worried only about increasing book sales.

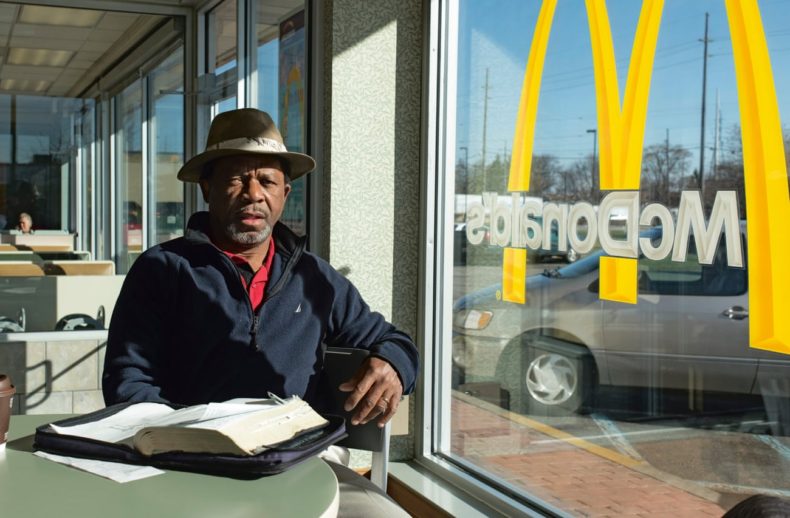

Chris: I wrote most of the book sitting in the back corner of my local McDonald’s and that of course attracted lots of questions. When I told people I was writing a book they just looked at my blankly, like I was crazy, and then would ask me what was it about or the title. I tried various things, and eventually found what resonated most was, “You can learn everything about America in a McDonald’s.” So that was also my working title in my head for much of the process.

Ann: And I know, because you’ve guest-posted on LWON several times, that this preoccupation of yours with the south-side of the class divide started pre-Trump. So you’ve spent years, looking with your ex-physicist, ex-Wall-Street-quant’s eye at people you call the back row — who are not the kids in the front row waving their hands because they’ve got the answers, who are also people you grew up with. And you called what you saw, Dignity.

Ann: What I learned from the book is that the differences between the back and front row are more than money, marginality, jobs, and education. That is, the back row kids chose lives and educations that weren’t going to get them fancy jobs and high salaries, and they did it only partly because their schools and towns and society hedged them in. They also chose the lives that were going to keep them close to their communities, their families. I believe that, I’ve seen it. And it’s admirable.

Chris: It is admirable, but it is not the life for me, or for many of those reading this. I left my small town as quickly as I could, and really never looked back. This book is about me doing that looking back, but as much as I might have changed my view on those who stayed, I am still glad I left.

One of my last trips, after almost 150K miles of other trips across the US, was going back to my rural Florida hometown (population 890) to see if what I had learned would give me a different perspective.

Chris: I did see things differently, certainly with more empathy, but I also saw, again, that the back-row wasn’t for me. I need the travel, the new experiences, the debates about books, the constant search for new ways of seeing. And as much as this project provided me a greater appreciation of faith, I also need science.

So while I hope readers come away with a better understanding of why someone might not go off to college and go easier on them for that choice, I don’t want to take anything away from wanting to be in the front row. I get it. I did it and I don’t regret having done it.

But I hope the front-row realizes that they have lots of blind-spots, prejudices, and unacknowledged privilege. Especially when it comes to how we look and think about those in the back-row.

Ann: I spent my life-before-Baltimore in the country and in small towns, and I can believe it was a blessed relief for you to get out of Dodge. But. You went back there, you got in your car and for years you drove all over God’s creation. Why ever did you do that? That is, given that you grew up in the back row, what did you think you had to learn? And the next question after that is, what did you learn that you didn’t already know, what was most surprising thing?

Chris: I think it was in 7th grade when I first learned about negative numbers and was so amazed and excited that I spent that evening doing every problem in the math book about them. Despite never being assigned any.

From then on I was so taken with math & science that 30 years later my life was literally sitting 12 hours a day behind a wall of computers flashing numbers. Mathematics, science, and reasoning had become the way I learned and thought about anything. It was who I was intellectually.

Chris: Yet after 10 years on Wall Street I had this nagging sense that maybe the undergraduate degree in math, the PhD in physics, the days spent building math models to think about global economics – was limited, and perhaps also wrong.

The financial crisis made that more than a nagging sense – so my long weekend walks to relax, began to change. They became more about learning from seeing and talking to people, rather than from numbers and statistics.

Eventually I walked into the South Bronx, a place that numbers said was simply bad & dangerous, and where I saw it as so much more than that. It is where I ended up spending three years listening to a group of homeless addicts and what it taught me was how limited a purely quantitative view was. It showed me how messy life was, how nuanced, and how wrong (and impossible) it was to only look at the world through the narrow window of numbers.

Chris: The most surprising thing that came from this was my views on faith (something I wrote a small piece early on in the process for on for you here). Looking back I had never expected to have my atheism challenged. Certainly not in the drug dens of the South Bronx, but that is what happened.

Part of it was recognizing a simply utilitarian value in faith. It was a more informed scientific view of religion. The realization that what the cold secular world that science so often offers up is just that, Cold & secular. Science is not very appealing and often hard for those dealing with trauma to see what “good” it offers.

Chris: But it became more than a utilitarian appreciation for faith. It became a realization that being educated and wealthy had removed me from the best evidence for the “truth” behind faith. When you shield yourself from the messy details of life it is easy to convince yourself that humans can figure it all out, that we all got it under control, or that with enough data, thinking, and computer power, we could figure it out. Maybe, just maybe, we couldn’t and can’t ever do so. Maybe there is stuff just too big and complex to understand and perhaps that is the essential truth.

Chris: Why did I drive everywhere? Eventually after having spent three years in the South Bronx, years that fundamentally changed how I thought about the world, I wanted to see if what I learned there was “translationally invariant.” Was it true only to this one neighborhood or was it true beyond that? So like a good researcher I drove to as many places as I could, so that on the whole I could feel comfortable that I’d represented the United States. Well, to one sigma at least.

Ann: I’ll remind our dear readers that sigma is physicists’ measure of certainty. And one sigma? Pfft. I’ll also repeat that Dignity’s alternate title was Humility. And then I’ll remember why we’re named The Last Word on Nothing: Science is first of all about discovery (the first word on everything). But the more science knows, the more it realizes what it doesn’t know (the last word on nothing). Curiosity and humility: the human condition.

________

All photos by Chris Arnade. You can buy his book here.

Great interview.